How do local electoral rules shape the provision of collective goods, specifically things society needs but few people want nearby? Looking at city councils, one important difference is between district elections—where each part of a city elects one council member— and at-large elections—where the city as a whole elects several council members each election. We find that district elections decrease the supply of new multifamily housing compared to at-large elections. However, by giving every neighborhood a “seat at the table,” district elections also increase the racial equity in where that housing is built. Still, this equity gain is problematic for long-run inequality as less new housing each year means higher housing prices, hurting low-income communities, renters, and first-time homebuyers.

Since 2001, over one-third of California cities have agreed to switch from citywide (or at-large) to district elections. This is important because at-large elections generally elect council members from a few wealthier, whiter neighborhoods in a city. As a result, switching to district elections increases the political influence of low-income, minority neighborhoods, which tend to be underrepresented in at-large systems. Driving this switch has been the California Voting Rights Act (CVRA), which lowered the burden of proof for demonstrating racial discrimination under at-large elections. Conditional randomness in which cities were targeted for CVRA litigation provided us with an opportunity to causally identify how the shift to district elections affects the housing supply.

To measure these effects, we collected aggregate housing data from every city in California from 2010 to 2019. To understand how the reform shaped the spatial distribution of housing within cities, we also reviewed minutes from every city council and planning commission meeting from 2011 to 2018 across 6 cities, totaling over 2,000 meetings, and built an original, geocoded dataset of all new developments approved within these meetings. Our findings, therefore, address two ways in which electoral institutions structure local power and distributive politics: how district elections affect how much housing gets permitted and where that housing goes.

First, district elections decrease the number of multifamily units permitted each year, but have no effect on single-family permits. This makes sense, given multifamily housing is politically vulnerable via discretionary review and elicits strong “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) backlash. The effect is concentrated in cities where we expect district elections to have the largest impact on minority representation: where there is a large minority population that is spatially segregated and currently underrepresented on the city council. This is consistent with expectations set by federal voting rights litigation (i.e., the Gingles test).

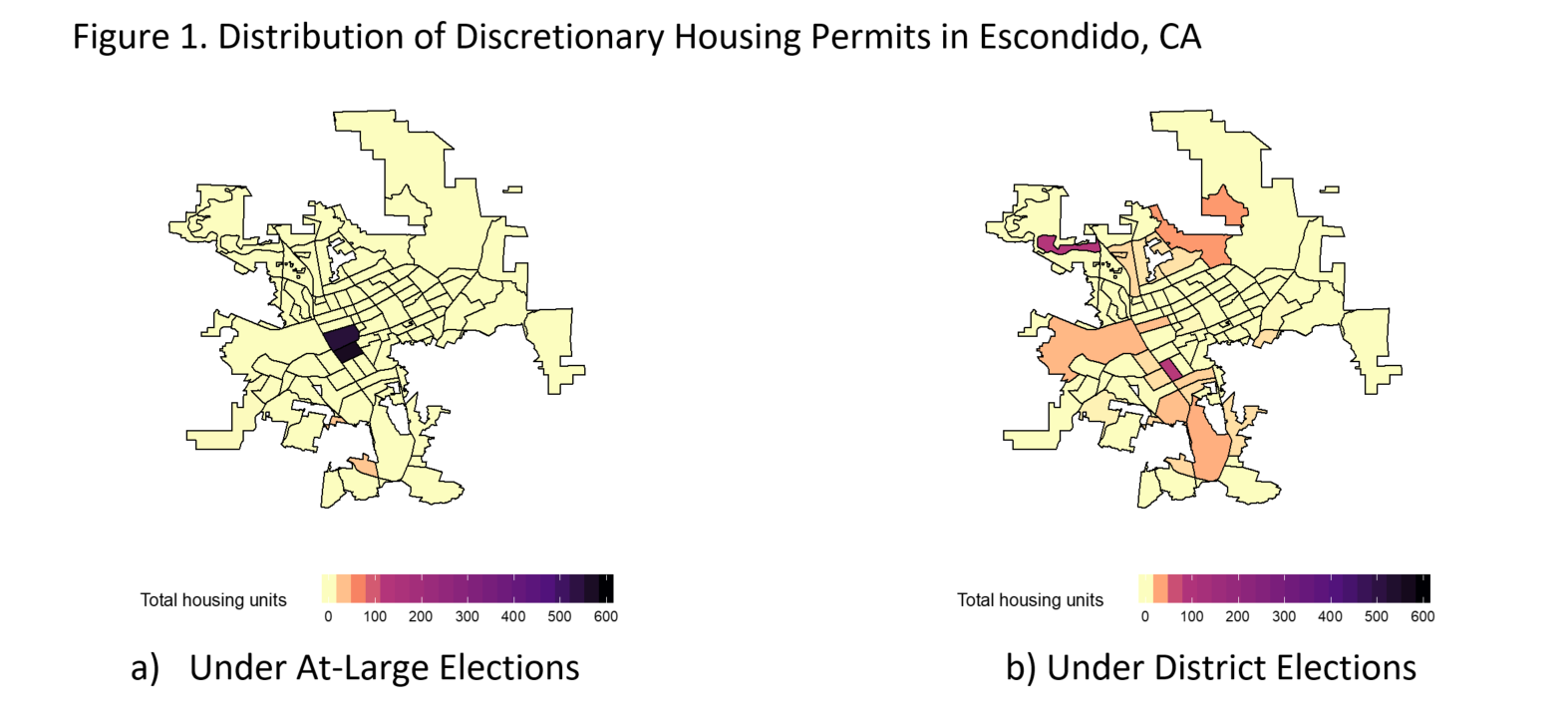

Second, district elections prevent politically disadvantaged neighborhoods from becoming “dumping grounds” for new locally unwanted land uses, like multifamily housing. Under at-large elections, minority neighborhoods absorb more housing annually than white neighborhoods. With district elections, there is no longer a difference between the amount of discretionary housing permitted in white and minority neighborhoods.

Figure 1 shows this dispersion of housing permitted via discretionary review in Escondido, CA under at-large elections (pre-treatment) compared to district elections (post-treatment). New permits move from a concentration in downtown, minority neighborhoods to the surrounding, whiter neighborhoods. This is our supply–equity trade-off. Districts lead to less multifamily housing, which is bad for long-run affordability. But greater neighborhood representation means a more equitable distribution of housing, breaking a long history of racial inequality in NIMBY outcomes.

Still, achieving both supply and equity is possible. Districts may be a good thing if the California state government passes stronger mandates for citywide housing production. Districts ensure that the top-down mandated housing is equitably distributed, rather than dumped in whichever neighborhood lacks a seat at the table. Beyond housing, local governments control most land use decisions. Thus, we expect our supply–equity trade-off to stymie the siting of many necessary land uses, from clean energy infrastructure to combat climate change to addiction treatment centers to fight the opioid epidemic.

Policies with concentrated costs and diffuse benefits are rarely popular. But locally unwanted land uses present a uniquely challenging concentrated burden, one subject to the spatial aggregation of voters. We have identified how the spatial scale of representation affects the trade-off between local interests and collective outcomes—between distributive equity and aggregate supply. Institutional design to overcome the problem of allocating concentrated costs should move beyond this trade-off to the pursuit of both goals.

This blog piece is based on forthcoming the Journal of Politics article “The Supply-Equity Trade-Off: The Effect of Spatial Representation on the Local Housing Supply” by Michael Hankinson and Asya Magazinnik , volume 85, number 3, July 2023.

You can read the research article on the JOP website. The empirical analysis of this research has been successfully replicated by the JOP and replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Michael Hankinson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at George Washington University. His research focuses on political behavior, local politics, and representation with applications toward housing and land use policy.

For further information visit his website and follow him on Twitter: @msghankinson