Image: Fernando Calvo // Ministry of the Presidency. Government of Spain. Pedro Sánchez during the first day of debate on his investiture on 22 July 2019. 2019–2020 Spanish government formation.

Unveiling gender's causal impact on government formation

Gaining insights into the impact of gender on government formation is challenging due to the private nature of negotiations between politicians. However, we overcome this obstacle by examining a unique institutional rule in the formation of municipal governments after Spanish local elections. This rule grants the leader of the first-most-voted party a significant bargaining advantage in the vote of investiture to become the new mayor.

In close elections where the most voted party led by a woman and the most voted party led by a man obtain a similar number of votes, the fact that one or the other enjoys the advantage is almost a matter of luck. These contexts are likely to be similar except for the gender of the winner of elections. This quasi-experimental situation provides an opportunity to test whether gender has a causal effect on politicians’ ability to capitalize on bargaining advantages and secure leadership positions in local government.

A gender gap of 24 percentage points (!)

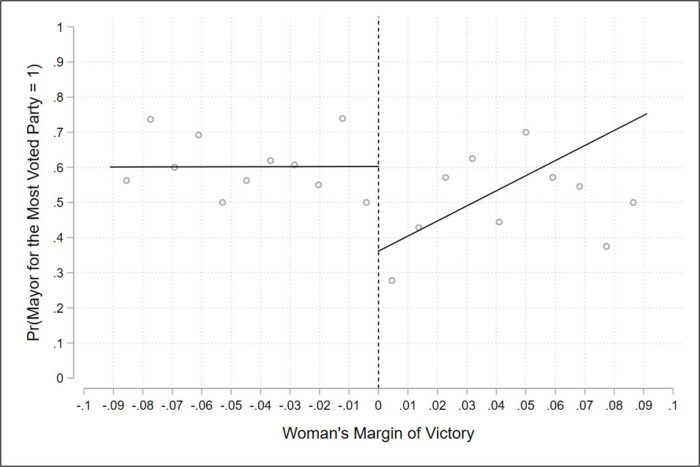

Through a regression discontinuity design (RDD), we compare the likelihood that the leader of the first-most-voted party becomes the mayor in localities where the most-voted female-led party won by a narrow margin of votes with localities in which a male-led party narrowly won. The results revealed a significant gender gap: female-led parties were 24 percentage points less likely to obtain the mayor’s office than their male-led counterparts in the same bargaining position. The graph exposes this break in the chances of becoming the mayor by illustrating on the right of the cut-off the situations where a women-led party wins the election and on the left where a men-led party wins. Women party leaders succeed less than 40% of the time, whereas men do around 60%.

Despite the disadvantage in securing the mayor’s office, we also find that female-led parties are just as likely as male-led parties to be included in the governing coalition. When a female-led party narrowly wins elections, it is significantly more likely for third or lower-ranked parties to take on the mayor’s office. This suggests that female leaders are more willing to concede cabinet leadership to other parties in exchange for access to the government, allowing them to maintain influence and drive policy changes from within the government.

A matter of choice or discrimination?

One possible explanation could be that women in politics prioritize policy influence over securing the highest-ranked position in the government. They are willing to forgo the mayor’s office in exchange for the ability to shape policies through other cabinet positions. This perspective suggests that female politicians are more policy-seeking and less concerned about the perks and privileges of the top leadership role. Another related possibility is that women employ negotiation strategies that prioritize collaboration and consensus-building over fierce competition.

But of course, outright discrimination could also play a role in this complex equation. It is possible that the rest of the parties in the council harbor biases against having a female leader in the government, resulting in a concerted effort to exclude them from the mayor’s position. Despite their demonstrated capabilities and qualifications, this bias could force female-led parties out of contention for the highest office.

Better representation, better governance

The fact that women face harder challenges in translating voter support into executive power has significant implications for the quality of representation. Uncovering the gendered nature of government formation processes and understanding the choices involved and the barriers encountered are crucial for promoting gender equality in political decision-making. Institutions strive to comprehend disparities, weaving a tapestry of just processes that grant equitable access to positions of influence. Electoral gender quotas, for instance, have boosted women’s participation in politics. Yet, the quest for inclusiveness falters at the top echelons. To bridge the gap, existing quotas must harmonize with targeted measures for top executive roles. This is essential for creating an environment that breaks the glass ceiling and ensures equal opportunities for women in top leadership roles. Only then can we truly harness the full potential of diverse perspectives and ensure inclusive governance for all.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Women who win but do not rule. The effect of gender in the formation of governments” by Alba Huidobro and Albert Falcó-Gimeno.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Alba Huidobro

Postdoctoral Scholar at the Department of Political Science, Stanford University. Her research interest lies at the intersections of comparative politics, elites’ political behavior, and gender, focusing on women’s selection into politics and governments.

Website: https://www.albahuidobro.com/

Twitter: @albahuidobro

Albert Falcó-Gimeno

Serra Húnter” Associate Professor in Political Science at the University of Barcelona. His fields of research include comparative politics, political economy, and voting behavior, with a particular interest in coalition politics.

Website: https://www.falcogimeno.com/

Twitter @afalcogimeno