On June 17, 2015, an avowed white supremacist opened fire on an evening prayer service being held at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine Black members. In the wake of these murders, activists called for removing the Confederate flag from South Carolina’s state capitol grounds. Less than a month later, the flag was gone: at the behest of the state’s Republican governor, South Carolina’s legislature overwhelmingly passed a law to remove it.

The Charleston massacre catalyzed a surge of activism that led to successful removals of hundreds of Confederate symbols in public places – including flags, monuments, and the names of roads. Further removals occurred after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 and the murder of George Floyd in 2020. What are the consequences of the removal of political symbols for the attitudes and behavior of ordinary citizens? Is it the removal of the symbols themselves that matters or debates around the symbols? Does distance matter?

What are the consequences of Confederate symbol removals for public opinion around race?

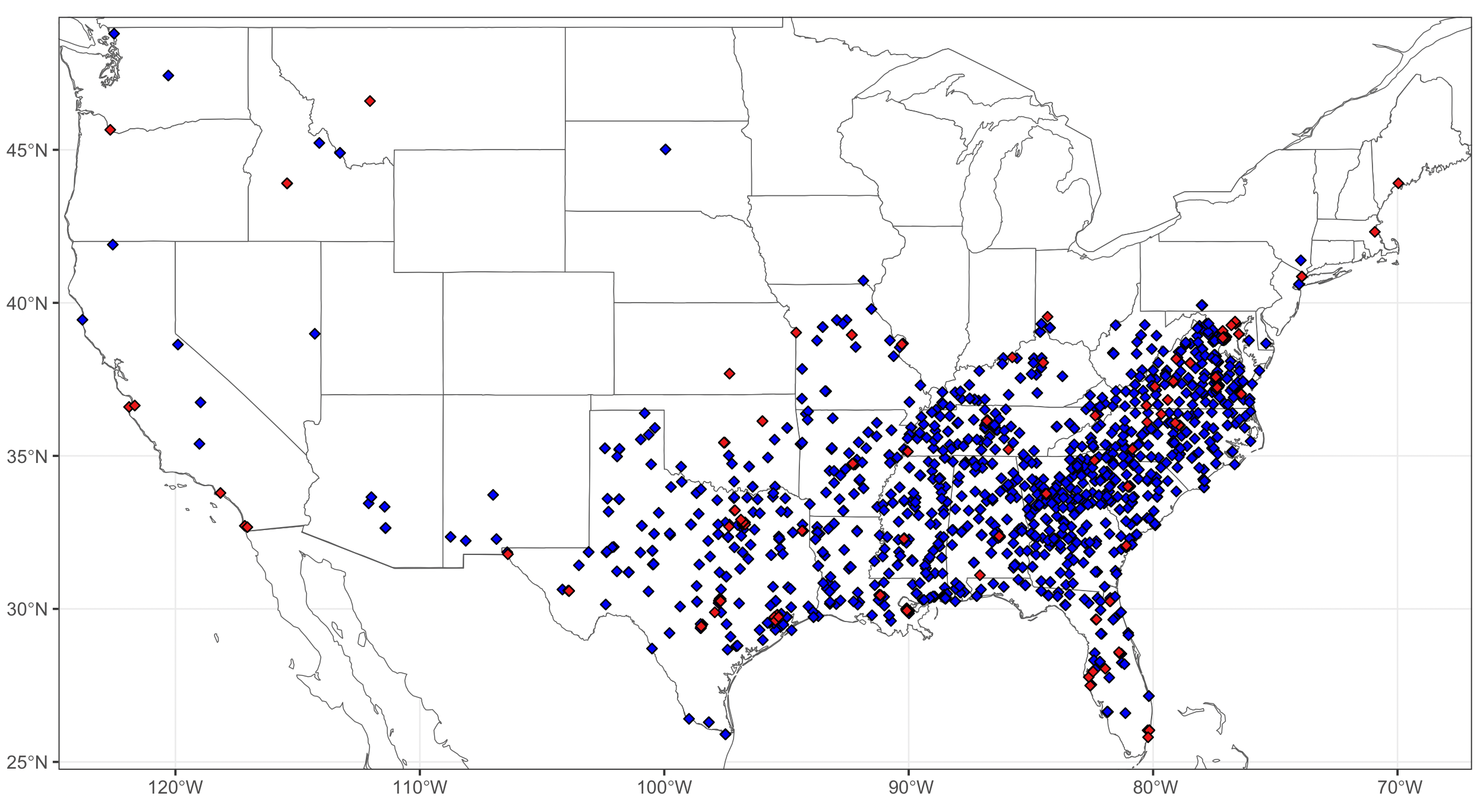

To answer this question, I use a comprehensive database of over 1,700 Confederate symbols compiled by the Southern Poverty Law Center. I augment this with original data collected on the dates of removals and media accounts of any public deliberation regarding these symbols (for both symbols that were ultimately removed and those left standing). I combined these data with contemporaneous survey data measuring attitudes on race across time and space.

To isolate the effect of symbol removals on public opinion, I leverage a design in which I compare racial attitudes in localities that had symbols removed with places where symbols were left in place. A causal interpretation of these effects rests on satisfying an assumption that racial attitudes prior to these removals were trending similarly in places with and without removals. For example, one might be concerned that symbols are more likely to be removed in places where racial attitudes were already liberalizing or in localities with specific demographics, like a larger Black population.

After addressing each of these concerns, I find evidence that – after the wave of symbol removals that occurred following the Charleston massacre – there was a reduction in racial resentment and increase in support for affirmative action. The former outcome is a canonical measure of racial attitudes toward Black Americans, while the latter is a noisier measure. These findings are similar for the wave of removals that occurred after the Charlottesville rally: localities with removals experienced an increase in warm feelings toward Black Americans.

Did these Confederate symbol removals affect behavior in a similar way to the effects on attitudes?

To answer this, I use racial bias-motivated hate crime data compiled by the FBI. I average the number of hate crimes against Blacks in a given year and examine the effects of the wave of removals after the Charleston massacre on anti-Black hate crimes, using the same design strategy. I find that anti-Black hate crimes decrease after symbol removals. These results are based on a smaller sample and not as statistically robust and should thus be interpreted cautiously. Nonetheless, they suggest that attitudes and more extreme forms of real-world behavior moved in unison in response to Confederate symbol removals during this period.

Is this really about the symbols – and not the debates about them?

Confederate symbols are hotly contested. Indeed, communities have engaged actively in deliberations over what these symbols represent to different groups of people and how to commemorate history in public space. Thus, one might worry that changes in attitudes and behavior are driven by the effects of debates over symbols, rather than the removals themselves.

Based on data that I collected using local news reports, it is indeed the case that most removals were accompanied by preceding deliberations (about 91 percent). However, a sizable share of symbols were debated but ultimately left standing. This allows me to isolate if there is still any effect of the symbol removals themselves when I subset the data to only consider active and removed symbols that were publicly deliberated. The findings hold: actual symbol removals transmit public signals about what arguments prevailed in these deliberations. Confederate symbols that were deliberated but remain standing do not transmit a similar signal.

How far reaching are the effects of these Confederate symbol removals?

Ultimately, I consider these effects at varying geographic levels: the county, zip-code, and distance-based bins (calculated to include zip-codes whose centroids fell within 5, 10-, 20-, 50-, or 100-mile radii from the symbols). I find evidence that these shifts in racial attitudes and behavior are concentrated at the most local level at which removals took place. Indeed, the effect sizes are larger and only statistically significant at the zip-code level. In the distance-based analyses, the results are most robust at 5mi and decay with increasing distance.

Conclusion

The results in this paper suggest that removals of Confederate symbols moved local opinion in a racially progressive direction. This may come as a surprise, given media narratives on backlash against salient removals. Although backlash to removals or even no effects, may appear in other forms or under other conditions, the findings here specifically highlight evidence that is more in line with a theoretical expectation of shifts in perceptions of norms around race at a hyper-local level. Whether the shifts in public opinion reflect changes in the acceptability of expressing racially prejudiced views in surveys versus changes in underlying beliefs remains an open question, as does the question of whether these effects endure. At the time of writing this post, a school board in Virginia voted to reinstate two schools with Confederate names, after their names were changed in 2020. Indeed, despite local changes to the public landscape of symbols, the ideology that underlies them may be sticky and return in some places.

Notes

Fig. 1: Removed symbols in red, standing in blue (valid as of 2019).

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Monumental Changes: Confederate Symbol Removals and Racial Attitudes in the United States” by Roxanne Rahnama.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Roxanne Rahnama is an IDEAL Provostial Fellow and Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Stanford University, and an alumni affiliate of the Identities & Ideologies project. She received her Ph.D. in Politics from New York University in 2024. Her scholarly interests lie in the study of status, race and ethnic politics, gender and politics, and symbolic politics in both historical and contemporary contexts. You can learn more about her research at roxannerahnama.com. Her X handle is @RoxanneRahnama.