Political scientists have often debated the role of propaganda in autocracies. For some, propaganda is primarily a tool of persuasion, designed to promote government policies, encourage pro-regime voting, or sometimes even violence. Others doubt autocrats’ ability to persuade, arguing that citizens must recognize the bias of propagandistic messages and treat them with skepticism; instead, propaganda may be used to dominate the public by intimidating or confusing it. You can be scared by the government’s messages even if you don’t believe the facts that they posit. However, the classic dichotomy between persuasion and dominance does not explain why so many in contemporary autocracies continue consuming propaganda, especially as alternative information sources are available.

A New Perspective on Propaganda

I develop a new understanding of authoritarian propaganda that helps explain the popularity of state media in consolidated autocratic regimes such as Russia. For example, Vladimir Putin, who enjoys strong and very consistent public support, often does not need to persuade ordinary Russians—many of them already share his ideology and worldview. Threatening and intimidating the pro-regime majority is even less meaningful. What Putin needs is to preserve and reinforce his existing support.

Autocrats such as Putin can spread a different kind of propaganda that is tailored to citizens’ beliefs and identities, telling them what they already know and like to hear. Such “affirmation propaganda” reinforces citizens’ pro-regime views, makes them feel better about themselves and their country, and acknowledges their grievances. Belief-affirming messaging helps state media outlets to present themselves as trustworthy while casting independent news sources as untrustworthy. Then, state-controlled media can exploit this trust when convincing becomes more important—e.g., when it is necessary to explain negative shocks and difficult times. Affirmation propaganda thus creates a “partisan” echo chamber that continually fortifies regime support.

I examine how this approach to propaganda works in Vladimir Putin’s Russia and how it maintains trust in state media and distrust toward independent media. The analysis is based on three surveys that I conducted in 2019 and 2020, including a large-scale online experiment with over 22,000 Russian participants.

Key Findings

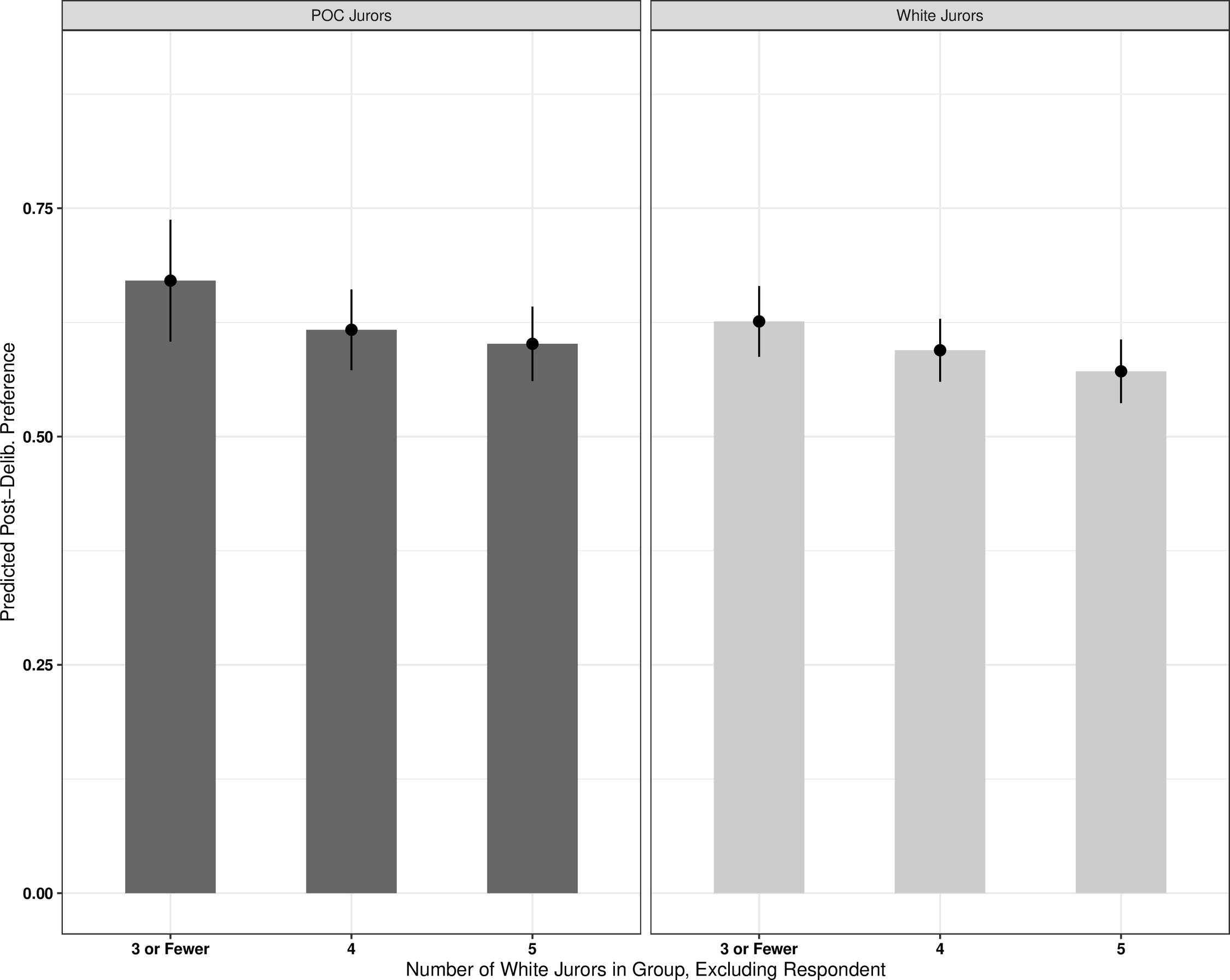

- Pro-Putin citizens, who constitute a large majority of Russians, often disagree with opposition-minded respondents about the truthfulness of political messages. Kremlin’s supporters believe positive messages about Russia much more often and criticisms of Russia much less often (Figure 1). In other words, there is a divergence of beliefs that state propaganda can exploit.

- Trust in Russian state media mainly comes from pro-Putin respondents; that is, this trust depends on political alignment.

- Russians clearly distinguish between state news outlets and independent, critical news organizations, and they put their trust in outlets that are more compatible with their political views. I set up an experiment, presented as a quiz that offered participants to test their ability to detect fake news. In this “quiz,” I randomly changed the news sources to which stories were attributed. I found that pro-Putin respondents very consistently believed in stories—even false ones—with state media logos and labels attached, as opposed to when the same stories were attributed to independent news outlets (Figure 2). In other words, pro-regime Russians were skeptical about more objective and truthful media.

- Importantly, pro-regime citizens react negatively when state media deviate from their normal propaganda line. In my experiment, critical news stories that were originally published by independent outlets were sometimes attributed to state news organizations. In such cases, pro-Putin respondents no longer trusted state outlets more than independent ones (Figure 2). Essentially, they penalized state media for being more balanced, which suggests that when citizens are biased in the regime’s favor, more “honest” reporting can backfire.

- Another important nuance is that Putin supporters notice the pro-Kremlin bias of state media outlets; they are just not bothered by it. I asked respondents to rate several prominent state media organizations on such criteria as accuracy, the degree of censorship, and political independence. While majorities agreed that propaganda outlets were not independent or neutral, most still believed these news organizations to report news accurately and completely.

Implications

My findings improve our understanding of propaganda in autocracies, showing that citizens often value pro-regime messaging and genuinely trust the outlets behind it. This makes counteracting authoritarian propaganda and disinformation very challenging. In particular, the availability of alternative, politically neutral outlets does not force propaganda to be more careful, and it does not prompt citizens to be more skeptical about state media. It is still important to support independent news media in autocracies, but their role as an antidote to propaganda is limited, as they mostly appeal to consumers who are already critical of their governments.

My research also shows that informed, skeptical citizens pose less of a problem for autocratic regimes than previously thought. When a large majority is attuned to the regime’s affirmation propaganda, autocrats can ignore more sophisticated and skeptical audiences and double-down on pleasing the sympathetic majorities.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Rethinking Propaganda: How State Media Build Trust through Belief Affirmation” by Anton Shirikov.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Anton Shirikov is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department, the University of Kansas. He has a PhD in Political Science from the University of Winsconsin-Madison, and he has recently been a Postdoctoral Scholar in Russian Politics at Columbia University. Besides JOP, his work has been published in Political Communication, the Quarterly Journal of Political Science, and other journals, and his analysis and comments have appeared in the Washington Post, the Financial Times, and other major news outlets.