Introduction

Citizens in low- and middle-income countries often grapple with inadequate access to basic public goods and services such as roads, water, and electricity. These services are not just essential for improving living conditions but also a top priority for voters in these regions. However, a critical question looms large: Do citizens effectively use elections to hold their governments accountable for delivering these vital services? A groundbreaking political science peer-reviewed article titled “Do citizens enforce accountability for public goods provision? Evidence from India’s rural roads program” sheds light on this crucial issue.

The study delves into the world’s largest rural roads program, India’s Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojna (PMGSY), which aimed to provide connectivity to one-third of the global population previously lacking road access. Analyzing data from 180,000 roads built across half a million Indian villages over two decades, the research presents findings that challenge conventional wisdom. Contrary to expectations, the provision of roads did not lead to increased electoral support for the ruling party. Even when leveraging population-based implementation rules to identify causal relationships, the study demonstrates that voters remained unresponsive to exogenous road provisions. Factors such as road quality, visibility, myopia, corruption, or attribution concerns did not account for this lack of responsiveness. These findings raise concerns about the strength of accountability in democracies, suggesting that it may be weaker than previously assumed.

The Significance of Studying Electoral Accountability

Public goods provision is a critical issue in many developing countries, where governments invest substantial resources in programs aimed at improving infrastructure and service delivery. However, in the absence of electoral incentives, politicians may prioritize high-visibility projects over essential but less glamorous services. Furthermore, governments worldwide invest in transparency and accountability initiatives to improve citizen oversight of development programs. The study, therefore, seeks to answer whether these costly state-led efforts yield the desired results.

Theoretically, there is a higher likelihood of observing accountability for road provision compared to more complex services like education or healthcare. However, existing research on information and accountability in developing countries has yielded mixed results, prompting questions about the validity of current theoretical models.

The PMGSY program presents a unique opportunity to advance our understanding of accountability for service delivery in India. Its vast scale and visibility allows for an unprecedented examination of electoral responsiveness. By investigating the electoral response to the program, the study aims to shed light on whether citizens hold politicians accountable for providing access to crucial services.

Key Findings and Contributions

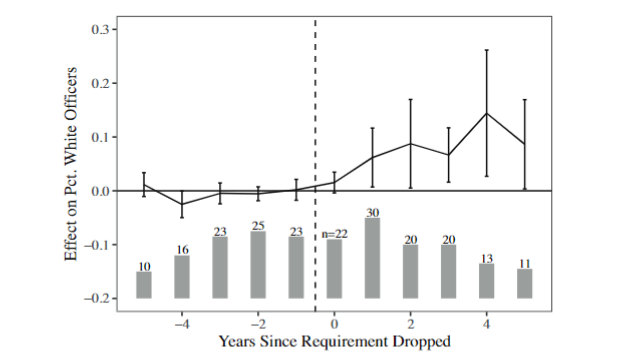

The study employs rigorous statistical analysis to examine electoral responsiveness to road provision in India. Despite the massive scale of the PMGSY program and the inclusion of accountability and transparency features, the research concludes that road provision did not lead to increased electoral support for the ruling party. This finding holds true across various electoral levels and time periods.

The study’s use of instrumental variable regressions strengthens the robustness of the findings, suggesting that endogeneity concerns do not explain the lack of voter responsiveness. Even in India’s most poorly connected state, Uttar Pradesh, the constituency-level results do not average out over positive and negative spillover effects.

Moreover, the study rules out key explanations for accountability failures, including issues related to road quality, salience, myopia, information availability, media coverage, and clarity of responsibility. Despite being visible and a top priority for voters, road provision did not significantly influence their voting decisions.

This research contributes to the literature on the political economy of accountability in several ways. It highlights the scale of the accountability problem in developing countries, particularly in the context of large-scale public goods programs. Additionally, it provides evidence that complements ongoing field experimental research and underscores the limitations of transparency initiatives in improving accountability. Finally, the study offers insights into why politicians might neglect state coordination failures in infrastructure development, indicating that voter unresponsiveness discourages the political oversight needed for effective program implementation.

In conclusion, the study on India’s rural roads program challenges our assumptions about electoral accountability for public goods provision in developing democracies. It underscores the need for further research and policy considerations to address accountability deficits in delivering essential services to citizens.

Notes

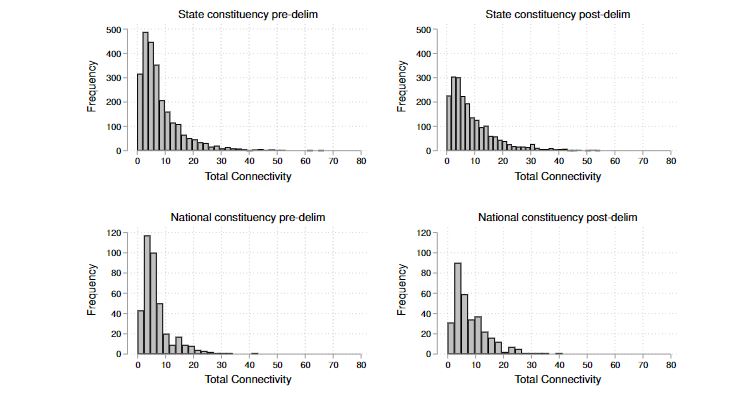

Figure 1: Total connectivity across state and national constituencies. The plot shows the distribution of connectivity for each of the subsamples indicated in the title. Onan average, PMGSY connected a substantive 8.3 percent of all villages (σ= 7.8) in each state constituencyduring the pre-delimitation period, and 9.2 percent of total villages (σ= 9.8) in the post-delimitationperiod. The comparative figures for the national constituency level are 6.9 percent (σ= 5.6) and 8.3 (σ=6.4) percent of total villages connected in pre- and post-delimitation period respectively.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Do citizens enforce accountability for public goods provision? Evidence from India’s rural roads program” by Tanushree Goyal.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Tanushree Goyal is an Assistant Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University. Her research interests lie at the intersection of comparative politics, gender and politics, and the political economy of development in the Global South. For more information, visit her website.