Over the past several years, U.S. elected officials and candidates have grown increasingly diverse. The most recent midterm elections were considered to have some of the most diverse candidates in several decades, with many states electing women, people of color, LGBTQ+, and Gen Z individuals for the first time to office. In both the U.S. and around the world, some places increasingly elect more diverse candidates, other places do not. What explains variation in office holding by members of marginalized groups?

Our answer to this question is that the key to understanding this variation is a social infrastructure of political participation that reduces the costs and raises the benefits of political officeholding. In many places, dominant groups can almost completely capture and control this social infrastructure, intentionally or unintentionally excluding members of marginalized groups. However, in places where there are even temporary disruptions to the dominant group’s control over this social infrastructure, marginalized groups can access this infrastructure to hold office both in the short and long term. Our paper focuses on the case of the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction. Until the Civil Rights Movement, Reconstruction was the high-water mark of Black men holding elected office. Yet, during this time, there was considerable county-level variation in the number of Black elected officials. We show that in places exposed to a county-level disruption of White men’s monopolization of the social infrastructure of political officeholding through a unique policy implemented by the U.S. military (called “contraband camps”), about two more Black officials being elected to political office during Reconstruction: a nearly 100% increase relative to similar counties without a contraband camp.

The Social Infrastructure of Political Participation

The social infrastructure of political participation refers to a set of individual and community-level processes that together reduce the costs and raise the benefits of political officeholding. On the individual level, people might have precursor-to-office roles (such as military or administrative experience) that provide them with information, expertise, and authority. These roles are also often connected to resource-rich external networks, such as parties or advocacy groups. At the community level, the social infrastructure of officeholding can include developing a local political “ground game,” a network of people who will mobilize and support a candidate. This community network also often contains role models and mentors who socialize other generations about holding political office. Together, the social infrastructure of political participation makes officeholding easier and more enticing.

Access to this infrastructure, however, is not evenly distributed across society. Some social groups–what we call dominant groups–enjoy a preponderance of material and nonmaterial power, and they use this power to capture and monopolize the social infrastructure of political participation. By monopolizing the social infrastructure, dominant social groups face fewer costs to officeholding and enjoy greater benefits. Members of marginalized groups face more significant costs and enjoy fewer benefits relative to dominant groups.

The central argument of our paper is that policies or events may disrupt dominant groups’ monopolization of the social infrastructure of political participation. When this happens, members of marginalized groups can hold precursor-to-office positions, cultivate external support networks, and build a political network at the local level, all of which together reduce the costs and raise the benefits of officeholding for members of marginalized groups. As a result, more members of marginalized groups should hold political office in places exposed to these disruptive policies or circumstances relative to other places.

The Context of the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction

We test our results in the context of the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction. Before the U.S. Civil War, virtually all political officeholders were White men. During the Civil War, as the U.S. Military moved South, it captured territory held by Confederate rebels and their supporters. In so doing, the U.S. military directly confronted the most pressing social issue at the heart of the conflict: enslavement. The U.S. military captured plantations on which enslaved persons resided, and self-emancipated, formerly enslaved persons would seek refuge behind U.S. military lines. At the time, military officials could not legally emancipate persons, but they were concerned about the potential for the Confederates to continue exploiting enslaved persons’ labor for the Confederate cause. U.S. officials created “contraband camps” to address this problem.

Contraband camps were places of continued exploitation of Black labor and oppression: Black persons in camps were often conscripted into paid labor positions. They were also noticeably different from the conditions of enslavement that preceded the camps: camps had schools, medical facilities, and court systems and were governed in part by community members who were appointed as sheriffs, judges, or administrators. Many of these camp leaders were Black persons–either formerly enslaved or volunteers from Northern activist societies who wanted to support the war effort. These camp leaders also gained important connections to the U.S. government, the Republican Party, and activist groups. These leaders and external networks actively politicized members of the camp community.

The experience of the contraband camp constituted a temporary disruption to White men’s monopolization of the social infrastructure of political participation. During this disruption, Black men could access the infrastructure by holding precursor-to-office positions and developing connections to external networks, and the broader communities in which these soon-to-be officeholders were embedded became more deeply politicized, even including the formation of party machines in two different camp locations. According to our argument, more Black officials should be elected in places with a contraband camp, relative to similar places in the same state without one.

Main Findings

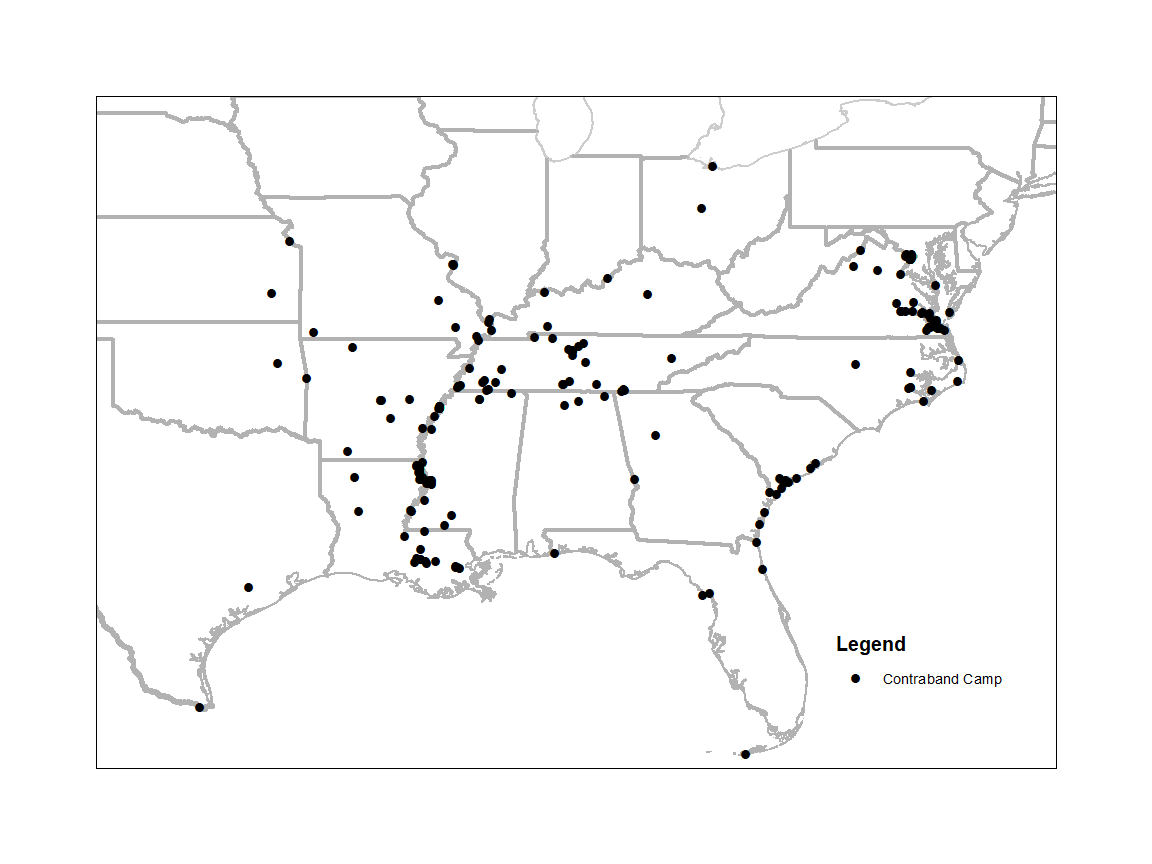

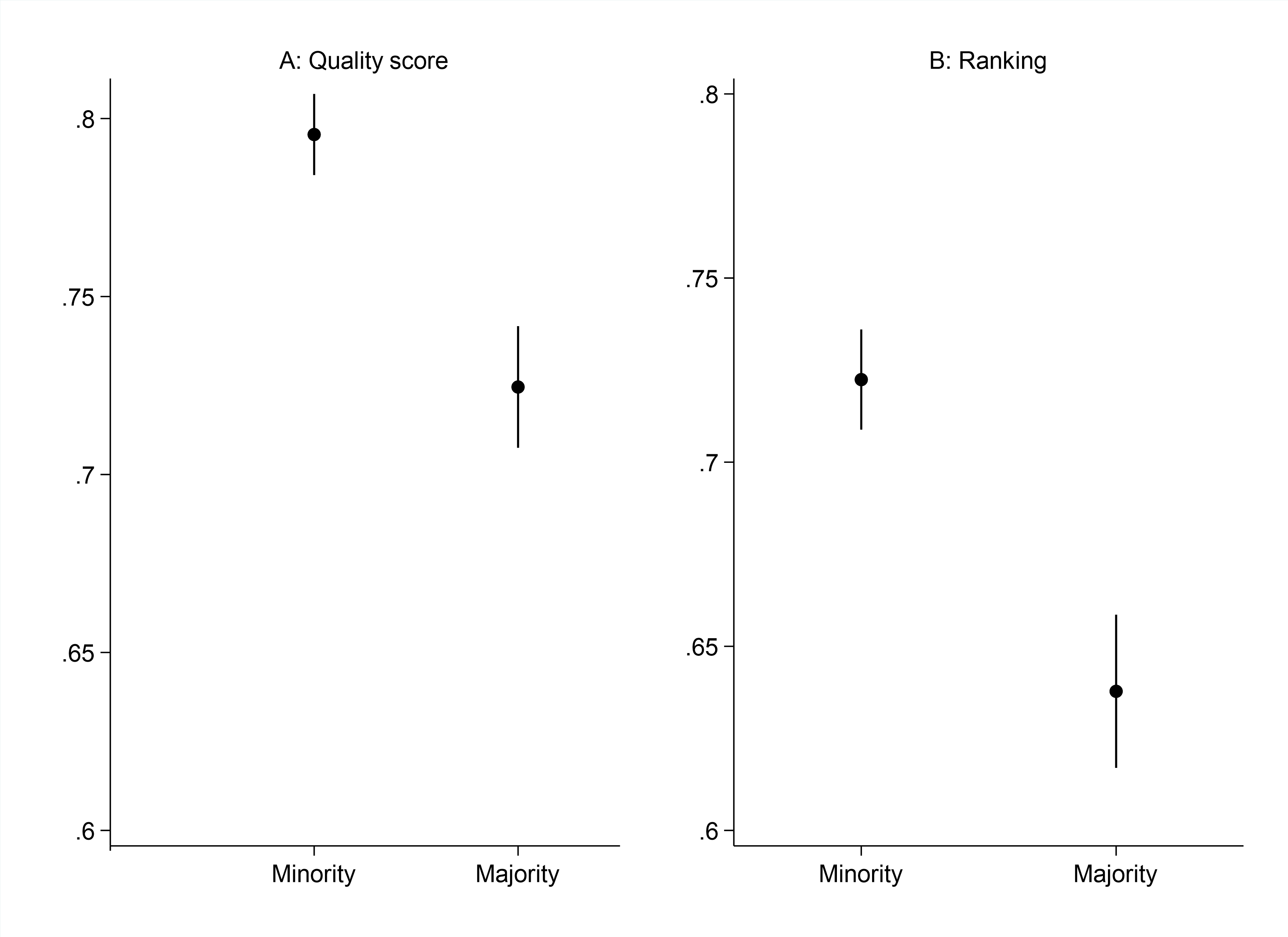

Notably, camps were placed in locations where it was beneficial to the U.S. military, not in places where there were unusually high levels of Black political activism (see Figure 1). Using a cross-sectional analysis of U.S. counties, we estimate the effect of contraband camps on Black officeholding. We find that places with a contraband camp almost doubled the number of Black men elected to political office: an effect size larger even than Union Troop presence and Freedmen’s Bureau offices.

Conclusion

Our results are critical for two reasons. First, our theory outlines how both individual and community-level processes operate together to facilitate officeholding, but that these processes are often captured by dominant groups. By disrupting an exclusionary social infrastructure of political participation, increases in marginalized group representation in political office are far more likely.

Second, our results speak to an important but understudied wartime phenomenon: contraband camps. Contraband camps were not only important during and after the war. Their legacy has even lasted to today, with some of the land still in the hands of the families of original camp members. Notably, control of this land is currently contested, with some of these homes and lands being sought by developers.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Explaining Variation in Political Leadership by Marginalized Groups: Black Office-Holding and Contraband Camps” by Megan A. Stewart and Karin E. Kitchens.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Megan A. Stewart is an Associate Professor at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. Her research focuses on the intersection of political violence and the redistribution of power. Personal website: www.meganastewart.org.

Karin E. Kitchens is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Virginia Tech. Her research focuses on the politics of education and the redistribution of power. Personal website: www.karinkitchens.com.