Political turnover is central the theory and practice of democracy. Yet, previous research on how turnover impacts governance and development has overlooked the unique incentives, constraints, and behaviors of election losers, focusing instead on the behavior of the winners. Understanding the politics of transition periods in between electoral defeat and the winner taking office is important because they are often long (Figure 1).

This article emphasizes the political strategies of lame-duck governments and their detrimental effects on the delivery of public services. I use “lame-duck” to refer to incumbents in the period between their electoral defeat and the end of their time in office. I argue that –at least where politicians have formal or informal discretion over the bureaucracy, and where bureaucratic norms for autonomous performance are weak– an electoral defeat of the incumbent leads to turnover among bureaucrats and declines in public service delivery during the transition period before the winner takes office.

The link between electoral defeat and bureaucratic disruptions highlights lame ducks’ unique incentives and their impact on democratic politics. Chief among lame ducks’ concerns is preparing for the vulnerability that comes after losing office, and laying the groundwork for their (or their party’s) return to office. At the same time, lame ducks have diminished incentives and ability to monitor bureaucrats, who may under-perform in a context of ambiguity and uncertainty.

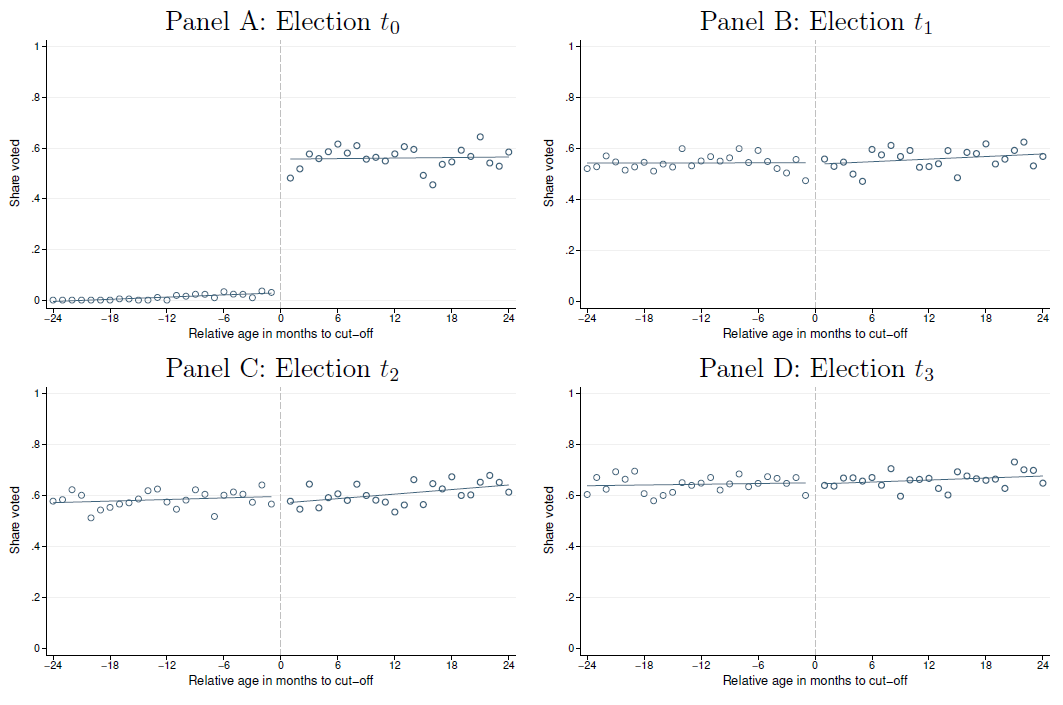

I demonstrate the effects of electoral turnover on bureaucratic shuffles and public service delivery using a close-races regression discontinuity design with data on Brazilian municipalities. This design essentially compares outcomes in municipalities where the mayor barely loses to those in which they barely win the reelection, in order to estimate the causal effect of an incumbent’s electoral defeat. Using fine-grained administrative data on public employment and healthcare services, I examine what happens both before and after the election winner is sworn in. I complement these causal estimates with qualitative evidence from in-depth interviews I conducted with politicians and prosecutors in several states.

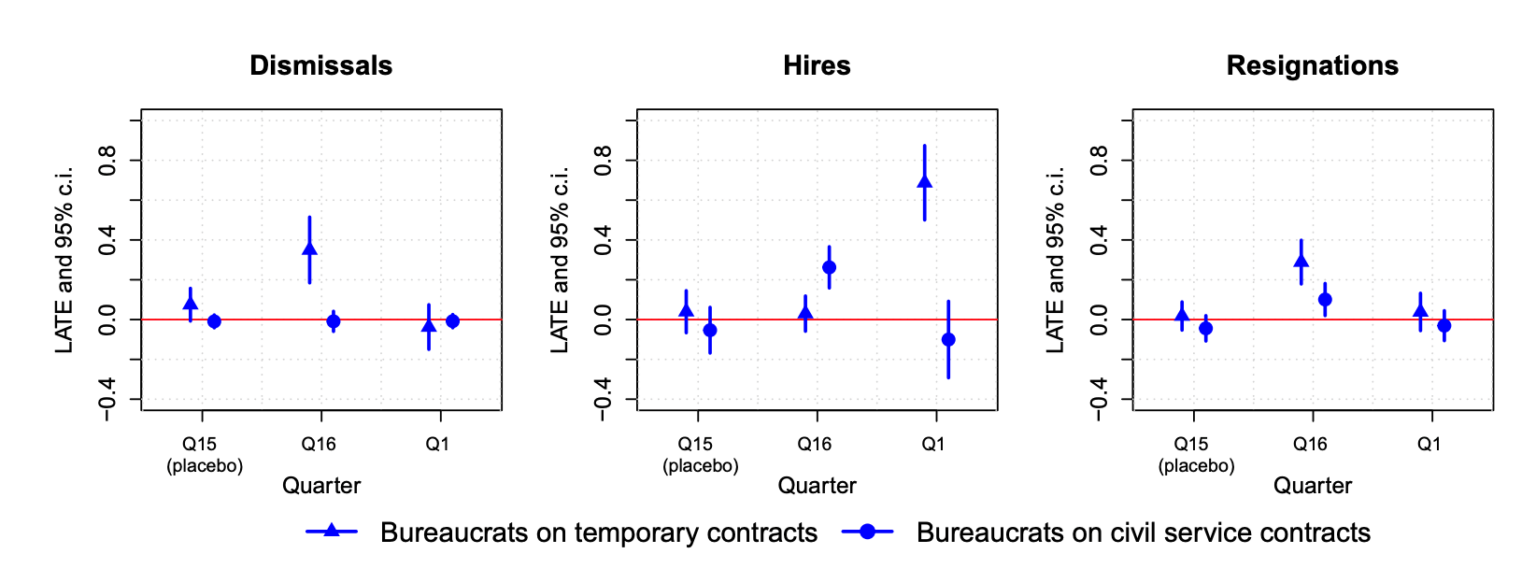

The results demonstrate that electoral defeat triggers significant dynamics of bureaucratic turnover immediately after the election}, both in the bureaucracy as a whole and among frontline service providers. Under lame-duck governments there are significant increases in the dismissal of temporary workers (by 42%) and the hiring of civil servants (by 30%). Interviews, media reports, and heterogeneity analyses suggest that lame-duck politicians use dismissals to improve their compliance with legal rules about hiring, and that they sometimes hire civil servants to limit the election winner’s fiscal capacity to hire their own supporters. Bureaucrats are also more likely to resign in the period following an incumbent’s defeat. Lame-ducks’ use of civil service hiring can hurt their opponents because election winners in fact use their discretion to hire as soon as they take office. When the incumbent loses, the hiring of temporary workers increases on average by 99% at the beginning of the new mayor’s mandate.

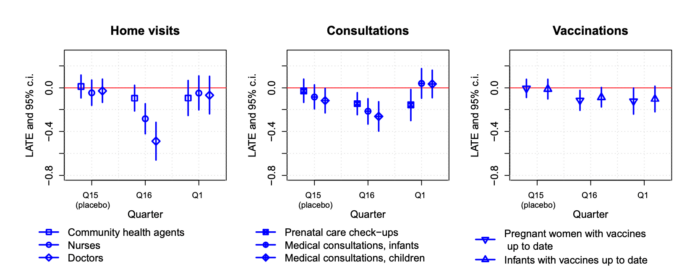

An incumbent’s electoral defeat also causes a significant drop in healthcare services during the transition period. Home visits by nurses and doctors, prenatal check-ups, medical consultations with infants and children, and immunizations for infants and pregnant women all decline in the last quarter of the mayor’s term. These declines, of between 8 and 39%, suggest that lame-duck politics can jeopardize citizen welfare, at least in the short run. Interviews and heterogeneity analyses suggest that declines in healthcare services are driven by a combination of turnover in the healthcare bureaucracy, disruptions to non-human resources (e.g., transportation), and weakening bureaucratic accountability under lame-duck governments, where politicians and senior officials are less able and/or willing to monitor and motivate bureaucrats.

These findings have important implications for how we think about political turnover and lame-duck governments. First, the article demonstrates that despite formal and informal rules limiting what lame-ducks can do, in practice these governments use their remaining time in office to exercise their discretion over the bureaucracy by pursuing unequivocally political strategies. Second, the fear of being prosecuted after leaving office can powerfully influence the behavior of lame-duck politicians during their remaining time in office. Third, neither public employment in the civil service nor the performance of civil servants is as insulated from political influence as is typically assumed (heterogeneity analyses reported in the article show that localities with a higher incidence of civil service hiring in the healthcare bureaucracy still experience marked declines in service delivery after an electoral defeat of the incumbent). Finally, the findings suggest that the dynamics of political turnover can jeopardize citizen welfare, at least in the short run. If political turnover depresses service delivery in a policy area that is both salient to voters and consequential for human development, it is plausible that it also disrupts other areas of government activity, at least those that depend heavily on human resources. A key policy implication of this study is that shortening the transition period between election day and the start of the winner’s term can be beneficial for service delivery and human development.

Note

Figure 1. Recent transition periods in a sample of 20 countries. Data correspond to the latest instance (up until January 1, 2023) when a new party reached national-level executive office through an election

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Turnover: How Lame-Duck Governments Disrupt the Bureaucracy and Service Delivery before Leaving Office” by Guillermo Toral.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Author

Guillermo Toral is Assistant Professor of Political Science at in the School of Politics, Economics & Global Affairs at IE University, and a Faculty Affiliate at MIT GOV/LAB. Guillermo works in the fields of comparative politics and political economy, with a regional focus on Latin America and Southern Europe, and a substantive focus on issues of development, governance, and corruption. For more information, visit his website.