In late 2022, the German government arrested two dozen people who were alledgedly involved in the planning of a far-right coup d’ètat. The larger group included several members of the German armed forces, including from special operations groups. In the midst of a surge in support for far-right parties, some voices warn of the potential link between the military and this ideology and the consequences it can have for democratic politics, following recent events in several Western democracies. Yet, to our knowledge, there was no empirical research that explored this relationship with quantitative data. This is what we have done in a new article, where we try to answer three questions: are the military more likely than the civilian population to support the radical right? Do military bases contribute to increasing the vote for the radical right in their vicinity? And in which countries are we most likely to observe this relationship between the armed forces and conservative ideology? We do so focusing on Spain and on the recent rise of the far-right party VOX.

Are individuals in the military more likely to support the far-right?

To answer the first question, we gathered a large number of surveys in order to compare the voting intention of members of the Spanish armed forces and the rest of the civilian population. Specifically, we pooled together more than 140,000 respondents across a number of national surveys between September 2018 and March 2021. We find that individuals in the military are much more likely than the rest of the population to support the far-right party VOX, particularly when we only look at right-wing individuals, both civilian and military. The graph below shows the gap in support for VOX between civilians and people in the military depending on self-reported ideology. For example, support for VOX is about 20 points higher among military personnel who place themselves at a 7 on the ideological scale than among civilians who also place themselves at a 7.

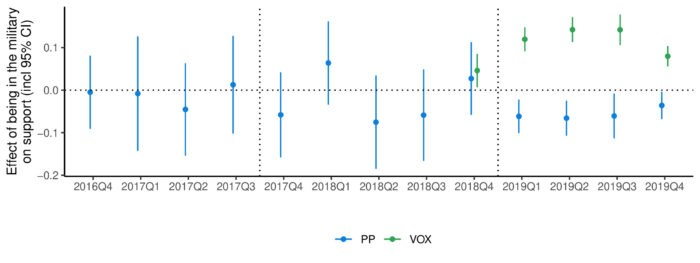

Interestingly, this gap is not constant across time. When we look at the civil-military gap in partisan support over time, we find that as soon as VOX emerged as a relevant national party in late 2018, individuals in the military became less likely than civilians to support the center-right party PP and more likely to support the far-right VOX. This implies that there was a dormant far-right constituency of voters within the centre-right that was mobilized to vote for the far-right once a viable far-right party emerged in the party system.

Do military facilities help increase far-right support?

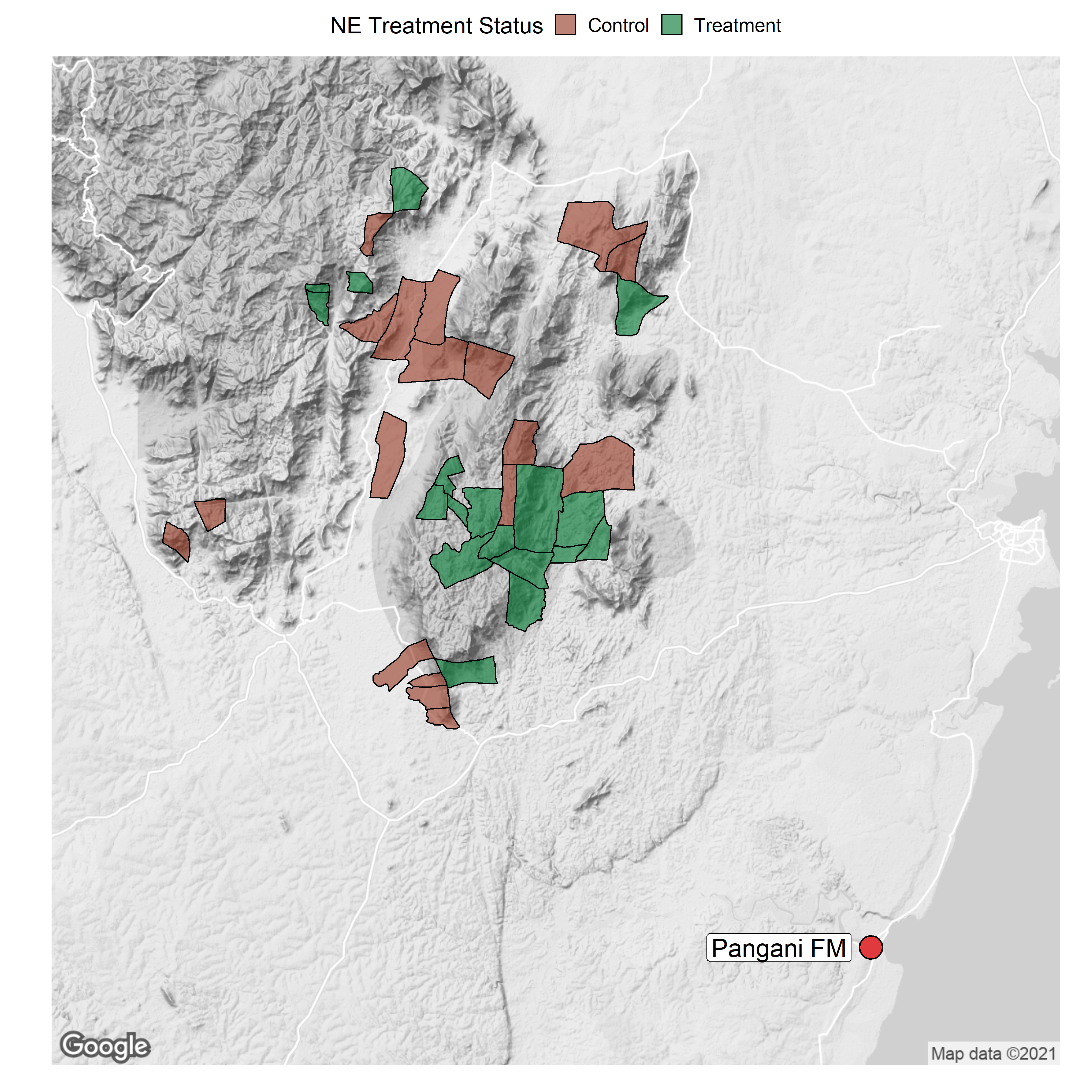

In the second part we try to answer two questions. First, is there higher support for VOX in areas with military bases, and thus where more military people people? And second, are individuals who live close to military bases more likely to support VOX? We hypothesize that the presence of military bases can increase far-right support because of daily face-to-face contact with military people or because of the exposure to Spanish nationalist symbols that are both prominent in military facilities and far-right narratives.

To do this, we put together a dataset at the level of census sections where we include electoral results from the 2019 elections and the location of military bases, based on publicly available information, as well as a number of other control variables. The results show that census sections with military bases, on average, show higher support for VOX, and that the same applies to census sections that are geographically close to military bases.

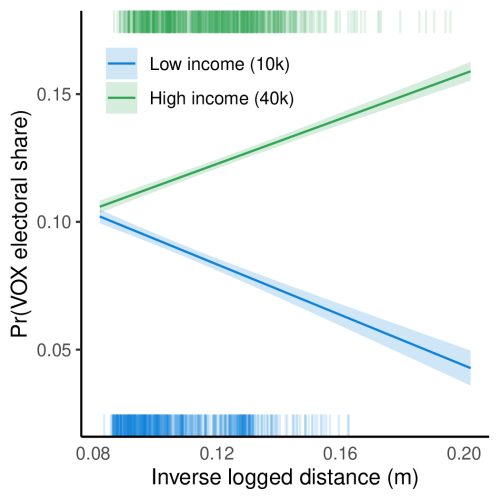

In addition, we also find that the diffusion effect seems to be more important in areas with higher income, where conservative ideologies are more prominent. In other words, wealthy neighborhoods that are close to military bases are more likely to vote for VOX than other wealthy neighborhoods that do not have bases nearby, but the same does not apply to low-income neighborhoods. As in the individual-level analyses, we find results coherent with the idea that the military is able to channel conservative individuals into far-right support.

The graph below shows how the vote for VOX changes according to its proximity to a military base, looking at the effect for a rich neighborhood (green) and for a poorer neighborhood (blue). To measure closeness, on the x-axis, we use the inverse of the logarithm of the distance, a measure where higher values indicate more closeness.

Beyond Spain

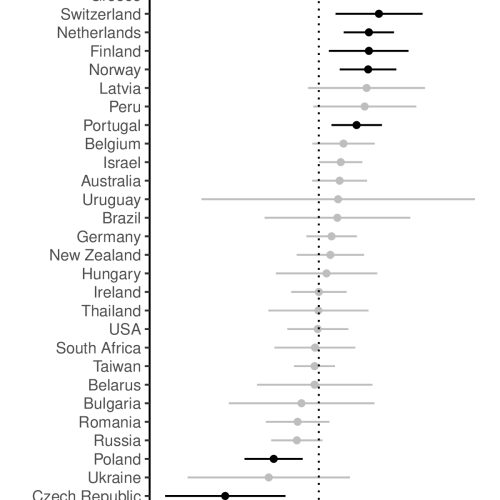

In the last part of the article we look at how generalizable these results are to other countries. Using survey evidence from the [CSES project](https://cses.org/), we compare the civil-military gap in self-reported ideology across multiple countries where we have a minimum number of respondents that claim being part of the military. The graph below shows this difference in ideology in each of these countries, where positive values (more to the right) mean that people in the military are more right-wing. Black bars indicate that the difference is statistically significant.

Our interpretation of these results is that the military is more right-wing in countries where the military has been historically linked to the control of internal dissent, usually revolutionary attempts, and threats to national unity. Among the countries in the top, for instance, the French army fought a colonial war and against Corsican terrorism, Greece and Portugal were military regimes where left-wing forces were branded an enemy of the nation, and Finland has been constantly threatened by foreign invasion. Spain’s position at the top is possibly explained because it adds up all the points: traditional role in controlling labour-related dissent, a right-wing military dictatorship, and separatist terrorism.

Conclusion

We find that far-right support seems to be greater within the barracks, and that part of this relationship is likely due to nationalism and other historical reasons. Given the importance of civil-military relations for democratic politics, we believe it is worth to keep looking into this.

Note

Fig. 1: Voting civil-military gap by ideology

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Rally ’Round the Barrack: Far-Right Support and the Military” by Francisco Villamil, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte, and José Rama

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Francisco Villamil is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Carlos III University in Madrid. His research is focused on the causes and consequences of civil wars and political violence. Personal website.

Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte is an Associate Professor in Quantitative Political Science at the University of Southampton. His research covers the the role of identities and ideologies on political behavior, with a focus on LGTBQ politics, far-right parties, and electoral politics. Personal website.

José Rama is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. His research focuses on elections and democratic politics, particularly populist and far-right parties.