To fight climate change, the world will need to quintuple production of certain minerals. We need cobalt and lithium for electric car batteries, silver and zinc for solar panels, copper and nickel for wind turbines, to name just a few. Hence, we can expect a mining boom.

Mining has well-documented negative effects for its host countries, predominantly low-income countries. While mining can boost government and local incomes, it may also involve unsafe labour conditions, harm to population health, environmental damage, and violent conflict. Thus, if we are serious about pursuing shared prosperity in the green transition, we must also be serious about curbing the negative effects of mining.

Effective policies must understand why these effects ensue. One well-recognised reason why mining might lead to violent conflict is the involvement of rebel groups. These groups might use revenue from minerals to fund violent conflict, or violently extort government, mining companies or individual miners.

Many existing policies to combat ‘conflict minerals’ are based on the premise that rebel groups are the principal source of violence around mining. For example, the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme aims to prevent diamonds whose proceeds fund rebel groups from being traded internationally, and the Dodd Frank Act Section 1502 forces companies to disclose if they use gold, tin, tungsten or tantalum from areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where violence occurs.

Our research however, finds that rebel groups are not the only reason why there is violence around mining sites. By extension, preventing this pernicious consequence of mining requires addressing other sources of conflict.

To see why there must be more to the mining-and-violence story, consider all mining sites on the African continent. There have been 4721 instances of violence within five kilometres of these, between 1997-2000. Over half of these instances took place outside of localised conflict zones where rebel movements are known to be present.

To understand why violence around mining sites also occurs when there are no rebels nearby, we worked with the non-governmental organisation International Crisis Group to study six sites, three copper-cobalt mines in the DRC and three gold mines in Zimbabwe, in areas without major rebel group presence. We sought to understand what separates sites with violence from those that remained quite peaceful.

A main difference between mines with and without violence, we found, was the potential for conflict between industrial and artisanal miners. Mining does not always require large companies with extensive machinery. There are also individuals and small groups who mine with little to no technology: small-scale diggers, or artisanal miners. In the DRC, they mine between 22 and 32% of cobalt, providing an income for an estimated 200,000 miners in one province of the DRC alone.

When large-scale mining companies and artisanal miners want to mine the same mineral deposits, violent conflict may, but not necessarily will, ensue. The most violent DRC mining site we looked at, saw an industrial mining company return to a site where operations had been long halted. This led to a cycle of violence: security forces violently evicting thousands of artisanal miners from the site, artisanal miners violently protesting lack of access, or returning to the site by bribing security forces, cueing yet more violent evictions. In Zimbabwe, a large-scale police operation during 2021 saw 25,000 artisanal miners arrested.

However, some of the mines we studied avoided such cycles of violence. At some sites, the potential for conflict between industrial and artisanal miners was non-existent, because minerals occurred too deeply underground for artisanal miners to reach. At others, industrial mining companies and artisanal miners successfully negotiated a form of subcontract, where artisanal miners could mine on parts of the site.

These case studies showed that conflict with artisanal miners is a key reason mining might lead to violence – and one that arguably is not well-addressed by current policies. But how big of a problem is it? To answer that question requires a quantitative analysis using data on mines and violence across the continent of Africa.

To do that, we had to address one more challenge: artisanal mining often goes unrecorded, so there is no consistent data on it. Furthermore, if artisanal miners seek out or avoid places with lots of violence, we might not be able to tell whether artisanal-industrial miner conflict leads to violence, or whether violent mines attract or repel artisanal miners. Not to mention the fact that mine owners might proactively make concessions to stave off artisanal mining and conflict.

To overcome these issues we use machine learning to predict which areas are suitable for artisanal mining, rather than which actually have miners. Drawing geospatial data on geology across Africa (e.g. the age of the bedrock, electromagnetism) we were able to predict artisanal mining – in areas where we do have reliable data – with between 72% and 97% accuracy.

Using this measure, we find that, as the global mineral price increases, violence increases three times as much around industrial mining sites also suitable for artisanal mining, compared to mining sites not suitable for artisanal mining. This increase is even more pronounced for industrial mining sites that are likely least subject to scrutiny – for example because their headquarters is in a tax haven. We conclude that industrial-artisanal miner conflict accounts for between 31% and 55% of all conflict around industrial mining sites.

Because industrial-artisanal miner conflict accounts for so much of the violence around mining, we need new solutions. The least violent Zimbabwean mining site we studied can give us ideas. There, cooperation between artisanal and industrial miners prevented conflict for several years. In principle, such cooperation can be codified by government authorities while adequately safeguarding conditions on industrial sites. USAID recently announced a £20 million programme to support such initiatives in the DRC, which is a helpful start. But given the expected mining boom, we need more governments, companies and consumers to recognise that artisanal mining is a livelihood strategy that will not soon disappear, and find sustainable ways to integrate them into ‘green’ supply chains.

Note

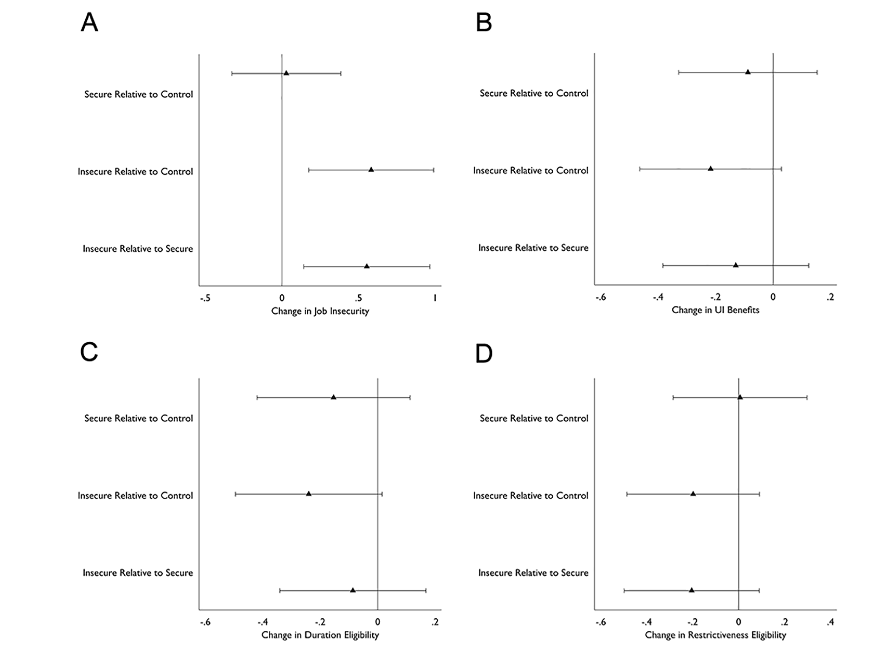

Fig. 1: The performance of the individual commodity classifiers on test setsNotes: Distribution of accuracy and ROC-AUC of commodity classification model on 50% test set across 50 different seedvalues. 2c represents copper and cobalt. 3t represents coltan (tantalum), tin, and tungsten.PricesWe obtain data on the price of most commodities from the World Bank Commodity Markets. Notes: Distribution of accuracy and ROC-AUC of commodity classification model on 50% test set across 50 different seedvalues. 2c represents copper and cobalt. 3t represents coltan (tantalum), tin, and tungsten.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Mining competition and violent conflict in Africa: pitting against each other” by Anouk S. Rigterink, Tarek Ghani, Juan S. Lozano, and Jacob N. Shapiro.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Anouk S. Rigterink is Associate Professor of Quantitative Comparative Politics at Durham University, School of Government and International Affairs (SGIA). Before that, she was Economics of conflict Fellow with the Empirical Studies of Conflict network at Princeton University and International Crisis Group, and Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Oxford. She holds a Ph.D. from the London School of Economics and Political Science. In her research, she investigates topics relating to development, conflict and security, and natural resources and the environment. She authored a paper on so-called ‘conflict diamonds’ and a paper asking how drone strikes killing terrorist leaders affect terrorist attacks and one on a civilian protection militia in South Sudan. She worked on a Randomized Controlled Trial investigating whether community monitoring can decrease deforestation in Uganda (part of Metaketa III), on a lab-in-the-field experiment designed to reveal how recalling violent conflict changes the deep determinants of individuals’ behaviour, and on a project on conflict between industrial and artisanal miners in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Tarek Ghani is an assistant professor of strategy at Washington University in St. Louis and a nonresident fellow of the Brookings Institution. Tarek’s research on political economy, development, and security has appeared in leading academic journals such as the American Economic Review. From 2020-2021, Tarek was chief economist and future of conflict program director at the International Crisis Group, where he previously served as senior economic adviser. He has also worked with the Center for Global Development, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Humanity United, the United States Institute of Peace, and the World Bank. Tarek holds a Ph.D. from University of California, Berkeley and a B.S. from Stanford University.

Juan S. Lozano is chief technology officer at Cofactor AI. He was previously a research specialist at the Empirical Studies of Conflict Lab at Princeton University.

Jacob Shapiro is Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University and non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Shapiro co-founded and directs the Empirical Studies of Conflict Project, a multi-university consortium that studies politically motivated violence in countries around the world.Shapiro has published research on conflict, economic development, and security in a wide range of peer reviewed journals. He is author of The Terrorist’s Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations and co-author of Small Wars, Big Data: The Information Revolution in Modern Conflict. Shapiro received the 2016 Karl Deutsch Award from the International Studies Association, given to a scholar younger than 40, or within 10 years of earning a Ph.D., who has made the most significant contribution to the study of international relations. He earned a Ph.D. in Political Science and M.A. in Economics from Stanford University and a B.A. in Political Science at the University of Michigan. Shapiro is a veteran of the United States Navy.