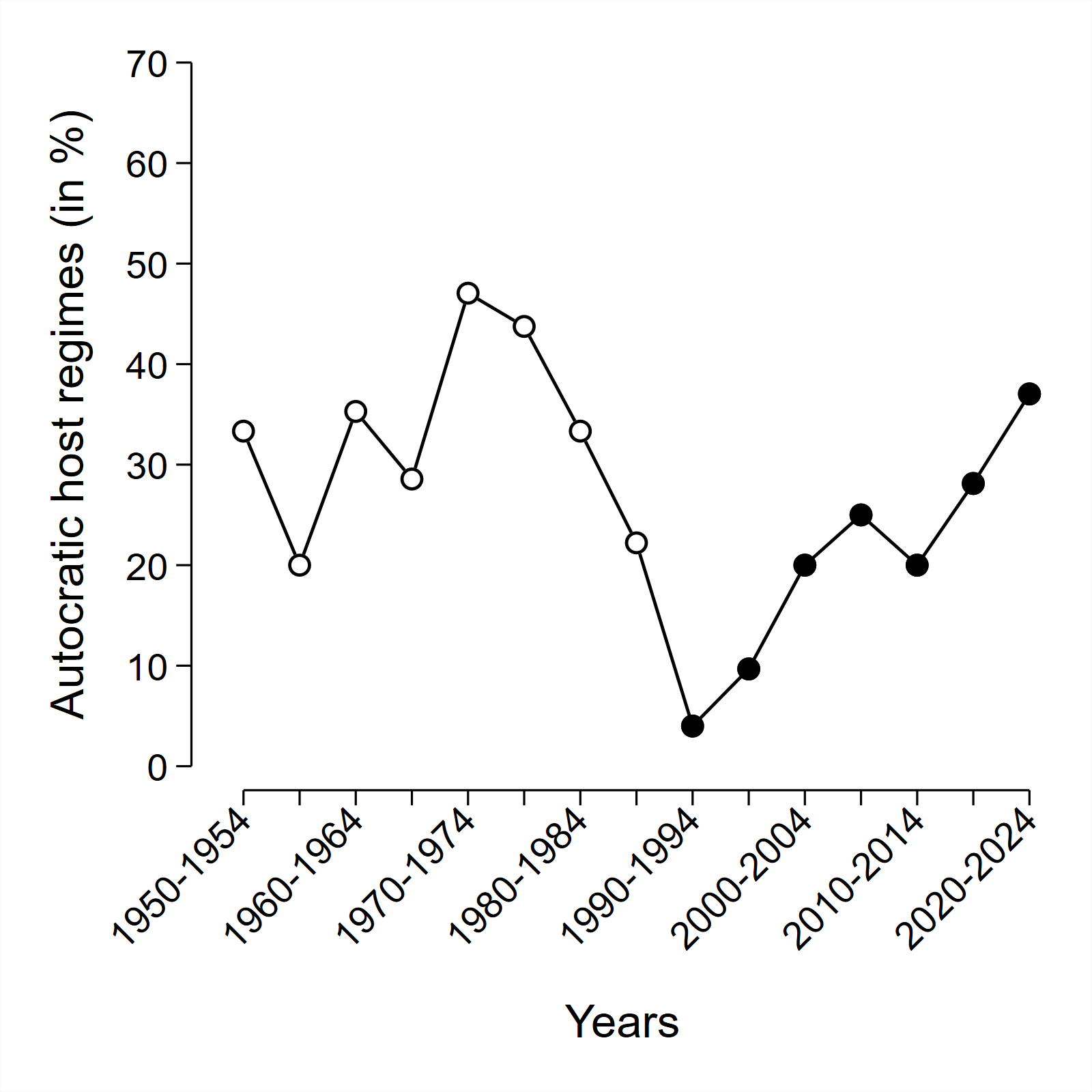

In recent years, international sport has walked on a political tightrope. More and more of the world’s most popular sports events have been hosted in dictatorships. Prominent examples include the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar and the Winter Olympics in China and Russia. Our data shows that the number of dictatorships hosting international sports tournaments is back to Cold War levels (Figure 1). With billions of spectators around the world, sports mega events offer host countries and their governments unprecedented opportunities to shine in the global spotlight

Journalists, pundits, and researchers have long suspected that China, Russia, Qatar, and other dictatorial host countries are engaging in sportswashing—that is, deliberately trying to use the popularity of sports to generate positive headlines, burnish their reputations, and improve their image among spectators and sports fans. For dictators, international sporting events may offer unique opportunities to improve their image and portray their regimes as peaceful, modern, and sympathetic. At the same time, a recent study of ours shows that major international sporting events tend to worsen rather than improve the human rights situation in host countries. Does sportswashing actually work? Can dictators use major sports events to improve their reputations and image abroad?

Using the World Cup’s opening ceremony to track changes in public opinion abroad

We conducted the first systematic study on whether dictators win their desired image boost by hosting a sports mega-event. Our study focuses on the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. The country’s monarchy ranks among the most illiberal host regimes in modern sports history (Figure 2).

We surveyed over 2,000 Germans before and after the 2022 FIFA World Cup to measure how the event affected their views on Qatar. We picked Germany because it is a sports-mad country, Europe’s largest economy, and a diplomatic heavyweight, which makes it a plausible target for Qatar’s image campaign. At the same time, German media had been highly critical of Qatar’s disrespect for the rights of migrant workers, women, and the LGBT community.

However, studying changes in public opinion around an international sporting event is anything but easy. Match results and the performance of one’s own athletes and teams can influence people’s opinions of the host country and its government. To avoid these potential distortions, we surveyed people just before and immediately after the start of the 2022 World Cup, before Germany played its first match. More specifically, we asked participants about their opinions of Qatar, the Arab world and Germany. We then compared how sentiments changed between the two waves.

The World Cup changed people’s opinions

In a nutshell, our study shows that dictators might benefit from sportswashing in two ways: by increasing support for the host region and by sowing doubts and distrust about democratic media and governance. Let’s look at this step by step.

Our results do not suggest that Qatar made direct publicity gains. The opening ceremony did not change perceptions about the monarchy’s international influence, technological progress, organizational capacity, attractiveness as a holiday destination, or its treatment of workers and the LGBT community. The only change we could detect was that after the start of the World Cup people in Germany seem to have become more positive about the situation of women in Qatar.

But our study did not stop here. In fact, our analysis shows that Qatar did reap broader publicity gains. Respondents became more sympathetic towards the Arab world overall. This may have been the result of the opening ceremony itself, which, like many tournaments before it, attuned the global audience to local traditions and presented a story from One Thousand and One Nights. Potential image boosts from major sports events seem to benefit wider regions, thereby spilling over to the host’s neighboring countries.

Are there any indications that Qatar managed to change how people in Germany looked at their own country? Yes! Most interestingly, and potentially also most discomforting, we also find support for indirect publicity benefits for Qatar. Respondents became increasingly critical of how German media reported on Qatar and German media more generally. This goes hand in hand with greater opposition to boycotts of autocratic hosts and a questioning of the quality of freedom of expression in Germany. Our findings also show that this translated into heightened skepticism towards the effort of strengthening the rights of the LGBT community and migrants in Germany.

Opinion changes are also visible on social media

A follow-up test that we conduced also shows that people’s behavior on the internet changed after the World Cup opening. Before the broadcast of the opening ceremony, most people on X (formerly Twitter) criticized FIFA’s alleged corruption and Qatar’s human rights abuses. During and after the opening ceremony, however, these voices went almost entirely silent. Instead, almost all the responding users complained about the critical reporting, which they felt was hypocritical and misplaced. And on Google, search terms such as “One-sided reporting” and “Lying press”—a common term used in German for “fake news”—spiked after the World Cup start. This suggests that World Cup in Qatar generated strong skepticism towards and rejection of German mass media.

The looming danger to liberal democracies

The findings raise important concerns for democratic countries. Not only can dictatorships use sports to positively change opinions, but it seems that the regimes can actually benefit from free media and its critical reporting, as they may unintentionally polarize liberal societies. Illiberal regimes could seize these opportunities and exploit the emerging divides between politicians, journalists, and the general population in order to further destabilize foreign democracies.

With more major sports events planned in authoritarian countries, understanding these effects is crucial. Qatar will host the 2025 World Table Tennis Championships and the 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup, the 2025 FIVB Volleyball Women’s World Championship will take place in Thailand, the 2027 World Athletics Championships is hosted by China, and the 2034 FIFA World Cup is scheduled to take place in Saudi Arabia.

Notes

Fig. 1: 1. Autocratic hosts of international sports events, 1950-2024: Note: Graph shows five-year shares of autocracies among all hosting nations of Summer and Winter Olympics and the world championships in athletics, basketball, cricket, football, handball, ice hockey, rugby, table tennis, and volleyball.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Does sportswashing work? First insights from the 2022 World Cup in Qatar” by Christian Göäßel, Adam Scharpf, and Pearce Edwards.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Christian Gläßel is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for International Security, Hertie School. His research focuses on fundamental questions of authoritarian politics and the inner workings of dictatorial regimes. You can find more information about his research here.

Adam Scharpf is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. His research focuses on political regimes and their production of loyalty and allegiance, both nationally and internationally. You can find more information about his research here.

Pearce Edwards is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Louisiana State University. His research focuses on repression and resistance in authoritarian regimes. You can find more information about his research here.