Responsible parties are conventionally defined as those capable of announcing their legislative goals and then passing them on the strength of their own members’ votes. In my forthcoming paper, I consider why majority-party leaders in the UK were able to build responsible parties by the 1880s and (mostly) maintain them since, while their counterparts in the US have never succeeded in building such parties.

Is it just different constitutions?

Most previous discussions have argued that the US’s constitutional structure—presidential, bicameral, and federal—makes it difficult for a single party to control the legislative process and, thus, for voters to assign responsibility for policy outcomes. The prospects for party control and accountability look much brighter in the UK—parliamentary, virtually unicameral since 1911, and unitary. However, constitutional differences can explain only so much. The UK did not change its constitutional stripes between 1832 and 1910, yet party responsibility was very weak at the beginning and very strong at the end of this period. The US did not change its constitutional structure after 1788, yet its parties varied widely over time in how closely they approximated “responsibility.” Thus, it makes sense to examine how political parties have adapted over time to the constitutional systems they faced.

Building “responsible” parties in the UK

I shall argue that, between the beginning and end of the 19th century, British party leaders centralized power and authority within their parties in three key ways, thereby building “responsible” parties. First, the governing party’s leaders centralized control over the legislative agenda in their own hands (as previous work—such as that by Andrew Eggers and Arthur Spirling (2014)—has shown).

Second, the out parties’ leaders centralized control over the decision to oppose the government’s bills in their own hands. My paper provides the first quantitative evidence regarding when this occurred, showing that the minority presented united opposition to only 50-60% of the government’s bills prior to the third reform act (1884) but then opposed 80-90% of government bills thereafter.

Despite the minority’s nearly unanimous opposition, British governments, after the third reform act, were able to enact virtually their entire legislative agendas by marshalling nearly unanimous support from their followers. The reason they were able to do so, I argue, is that leaders in both parties had centralized control over their followers’ nominations in their own hands over the 19th century (as shown in my previous work with Tobias Nowacki (2021)). This gave them a potent tool which they used mostly to reward loyalists (and sometimes to punish dissidents).

The majority party’s “weakest link” problem

To appreciate the value of nomination control, it is necessary to consider a problem that majority party leaders in both the UK and the US faced. Whenever the majority sponsored a bill, the opponents of that bill had a natural strategy. They could identify the bill’s most weakly committed supporters and convince just enough of them to abstain or oppose it. Often, this involved finding members, some of whose constituents opposed the bill, and stirring them up, thereby raising the electoral risk of voting with the majority. This tactic of attacking the “weakest links” in the majority’s coalition on each bill is widely recognized in the literature on legislative voting.

Theoretically, the majority leadership’s best response to a looming weakest-link attack is straightforward. They can allocate “side payments” so as to make every member of the coalition supporting their bill equally difficult to convert to opposition or abstention. This makes the opposition’s task as difficult as possible.

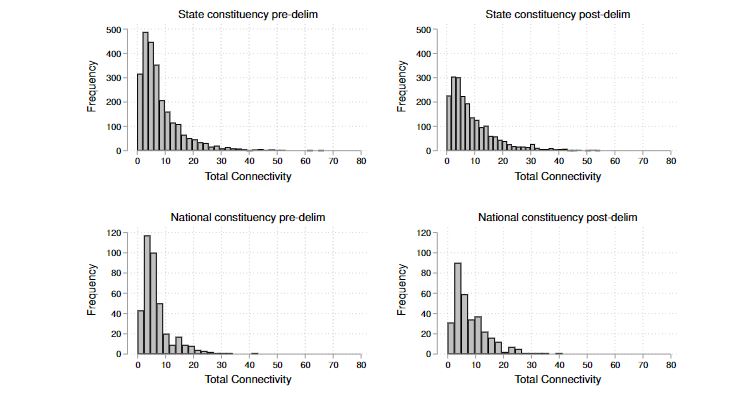

It is at this point that one can appreciate the value of nomination control. American party leaders must arrange “side payments” for their weakest-link followers on a bill-by-bill basis. Payments are tangible and costly—things like contributions to campaign funds, scheduling pet bills for consideration on the floor, and arranging pork-barrel projects for a member’s district. In contrast, British party leaders can offer a single “side payment”—protecting their loyalists by helping them transfer to another district, should their vote on a particular bill displease their current constituents (another important feature of the British system is that candidates can stand for election in any constituency in the UK; there are no residency requirements). My forthcoming paper provides evidence that this practice of rewarding loyalists with better nominations began fairly soon after the first reform act and strengthened over time.

How the US differs

The 19th century US paralleled the UK as regards the centralization of agenda power in party leaders’ hands (with the adoption of “Reed’s rules” in 1890). However, minority party leaders in the US were never able to organize the kind of consistent opposition to majority-party bills that their British counterparts managed. Moreover, when the American minority did present united opposition, majority-party leaders found it difficult to pass their bills—since they had to arrange costly “side payments” for a significant number of their followers. In effect, American majority-party leaders faced a budget constraint on how often they could undertake partisan legislation successfully.

I argue that the necessity of paying bill-by-bill “side payments” in the US is one important reason that recent American majority parties, although strongly polarized from the minority, have been relatively unsuccessful in articulating and enacting a legislative program. Certainly, bicameralism and presidentialism also play a role. However, if US party leaders could control nominations in both chambers of Congress, the cost they faced of articulating and passing a majority-party legislative agenda would be dramatically reduced. Thus, the very different structures of nomination control are an important part of why the US and UK have differed so dramatically in party “responsibility” for so long.

Notes

Figure 1: Opposing the government’s bill passage motions, 1835–1900.Author’s calculations from Eggers and Spirling (2014a). Upper curve (con-necting the diamonds) shows the share of the government’s bill passagemotions that the minority party opposed; the middle curve (connecting thesquares) shows the share they unsuccessfully opposed (i.e., the minority rollrate). The lowest curve is the smoothed gap between the upper and lowercurves. The short parliament of 1885–86 is not displayed.5. I count the following items as bill passage motions: third readings,motions to pass the bill, motions that particular clauses“stand part of thebill,”supply motions, and motions to ingross. Bill passage motions areattributed to the government if a majority of MPs from the governingparty supports passage. In practice, over 80% of these motions werewhipped by the government by the 1840s, with thatfigure increasingslightly over the rest of the century.

References

Eggers, Andrew C., and Arthur Spirling. 2014. “Ministerial Responsiveness in Westminster Systems: Institutional Choices and House of Commons Debate, 1832–1915.” American Journal of Political Science 58(4):873-887.

Cox, Gary W., and Tobias Nowacki. 2023. “The emergence of party-based political careers in the UK, 1801-1918.” Journal of Politics 85(1):178-191.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Comparing ‘responsible party government’ in the US and the UK” by Gary W. Cox.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Gary W. Cox is the William Bennett Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University. For more information, visit his website, https://politicalscience.stanford.edu/people/gary-cox.