Each year, the US spends millions on academic and cultural exchange programs. Motivated in promoting liberal values and democratization, these programs bring foreign students, scholars, and military officers to top US institutions. Similar government initiatives exist elsewhere: democratic and authoritarian states alike dedicate substantial resources in attempts to expand their cultural influence and foreign policy agenda. Empirical research on the policy implications of educational exchanges, however, remains scarce.

Does exposure to liberal norms, as part of educational exchanges, make individuals more supportive of liberal policies? On the one hand, individuals attend college during their most formative years. It is possible that taking a course on human rights or political participation could prompt a foreign exchange student from China or Russia to question some of the official information put out by their government. On the other hand, even at a young age, individuals tend to have strong pre-dispositions. Perhaps, one would be naïve to think that taking a handful of classes would cause Xi Jinping’s daughter, a Harvard graduate, to challenge her father’s illiberal practices.

To find out, we collected and analyzed data on the education of all country leaders from non-OECD countries between 1945—2015. We find leaders that attended any university are more likely to implement liberal democratic reform than leaders that did not. Only leaders that attended university in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, or New Zealand, however, are also more likely to implement other liberal policies, such as judicial reform, human rights protections, and trade and financial openness.

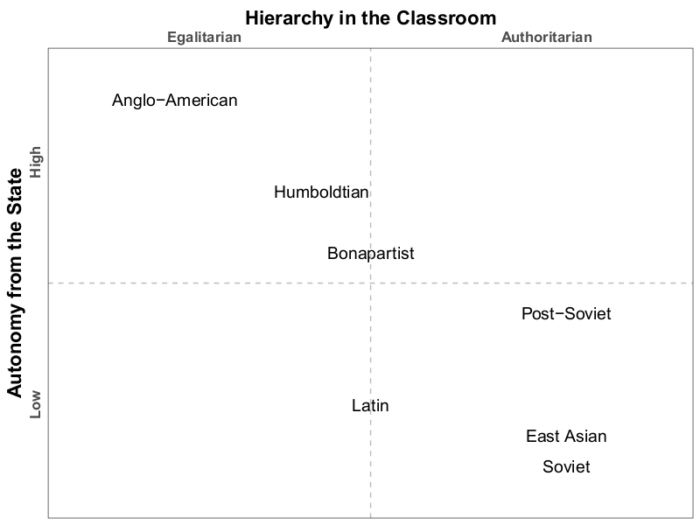

This latter finding intrigued us. Why would leaders trained in, say France or Germany, be less liberal on economics and legal reform than leaders trained in the US or UK? To answer this, we delved into education research, as well as reviewed university websites, curricula, and even textbooks. What emerged from this work was a two-dimensional typology of national education models around the world.

The first dimension represents university autonomy from the state, in funding and oversight. The central tension between universities and governments hinges on the core preference divergence. Governments expect clear deliverables and immediate payoffs in the form of a ready-made workforce and patent-ready research. Universities, in contrast, prioritize long-term goals, such as building world-class research facilities and attracting top academic talent in all areas. The result is more autonomous universities have a wider selection of course offerings and more general education requirements. Conversely, less autonomous universities specialize in technical and applied fields at the expense of the social sciences and humanities.

The second dimension is egalitarianism in faculty—student interactions. Less hierarchical interactions help students internalize the content of social science and humanities courses, which is not easily taught solely from the lectern. Egalitarian environments, particularly in smaller, upper-level courses, encourage students to probe, critique, and evaluate theories for their logical consistency and empirical evidence.

A university’s position within this typology corresponds to its ability to inculcate classical liberal values in its students. Through the breadth of their social science and humanities curricula, autonomous and egalitarian institutions introduce students to core social and ethical issues, such as the value of a representative government, free markets, human rights, and equality. In contrast, less autonomous and more hierarchical institutions offer fewer classes on these topics. The content of political science courses in Russia and China, moreover, focus more on descriptive rather than analytical features (who serves in a specific office versus why trade legislation differs between political systems) and may omit some content altogether (what national characteristics correlate with poor human rights protections).

As shown in the figure, institutions in North America, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand—a grouping adhering to the Anglo-American model—tend to rank higher than other models on both autonomy and egalitarianism. Compared to the Anglo-American model, universities in Western Europe (Humboldtian, Bonapartist) are significantly more dependent on the state, and this dependence comes with a substantial degree of oversight. For example, Western European universities have fewer general education requirements for their technical majors. Less than half of continental European countries have dedicated liberal arts degree programs, with only three—Germany, Netherlands, and Italy—having more than one such institution. This difference, and the correspondent limits in social science and humanities courses, explains the empirical result we found surprising earlier: that leaders educated at Anglo-American institutions are more likely to implement liberal reform across policy areas than leaders educated in Western Europe.

This analytical model suggests another testable implication. Even at autonomous and egalitarian institutions, student curriculum exposure to classical liberal values varies by major: students specializing in the social sciences and humanities receive greater exposure to classical liberal values than students that only enroll in required general education courses. By implication, leaders who studied social sciences and humanities should be especially likely to pursue liberal policy reform. To assess this, we also collected data on leader specialization at university, and find that leaders with economics and law degrees—the most popular majors in our dataset—are the most likely to implement liberal policies in all areas.

Our findings highlight that education is an important foreign policy instrument. Hundreds of top-ranked universities in the US and UK play no small part in these countries’ relative success at spreading their ideology and values throughout the world. Compared to other forms of power projection, such as troop placements or arms transfers, education is a relatively cheap tool for states, such as the US and the UK, to promote a liberal international order or, for its geopolitical competitors, to undermine it.

The effectiveness of higher education as a form of soft power, however, is neither automatic nor everlasting. It requires continued care and investment. Efforts that undermine university autonomy and egalitarian classrooms—such as government-intervention in curricula or unfunded mandates—weaken this form of geopolitical influence. Governments and politicians that intentionally undercut their world-class universities by treating education as just another issue to score cheap domestic political points—an increasing trend in North America and Europe—do so at the expense of their countries’ long-term global influence.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Schools of Thought: Leader Education and Policy Outcomes” by Mark David Nieman and Max Allamong.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Mark David Nieman is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Toronto. His research focuses on major power competition, international security, and political economy. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter.

Max Allamong is a Postdoctoral Associate with the Duke Initiative on Survey Methodology at Duke University. His research focuses on public opinion and political polarization. You can find more information about his work here.