How the media shapes people’s views on political and social issues is a vital question for scholars and the public alike. The question is particularly relevant in the developing world, where new, local, and independent radio and TV stations are beginning to reach people who previously had little to no media exposure or who have only ever received news from tightly controlled government sources. Does access to independent news sources affect people’s interest in and knowledge about politics and their broader social worldview?

Answering this question is tricky. Simply comparing the political and social views of people who listen and don’t listen to independent media only gets us so far since the kinds of people who decide to listen to independent news in the first place are different from those who choose not to. Some studies have tried to randomly expose people to independent media — for example, by sitting people down and exposing them to programs of interest — but this experimental approach has drawbacks in terms of naturalism. Simply put, it doesn’t emulate what everyday media consumption looks like in the real world.

A “natural” experiment

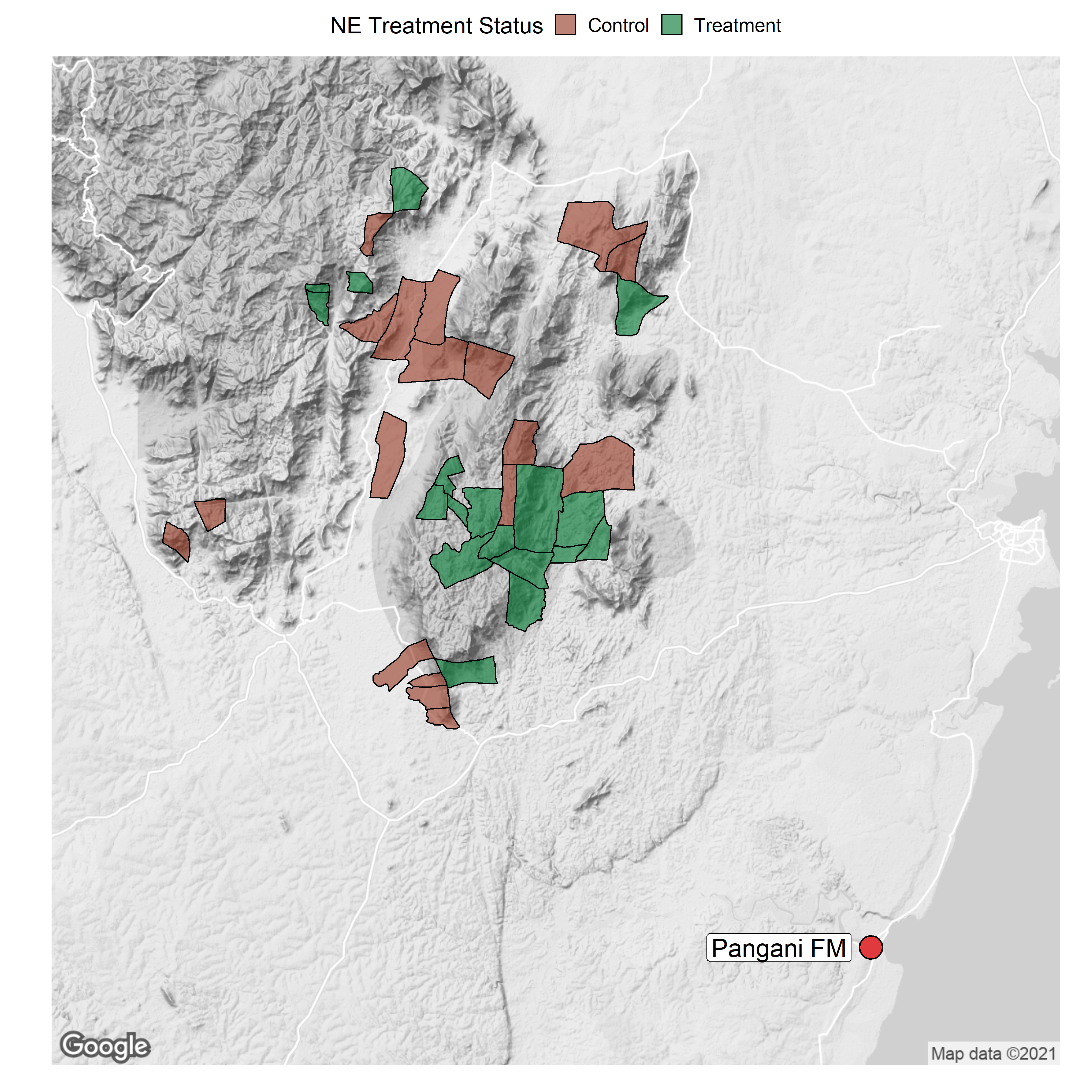

To get around these issues, our study took a unique approach. We partnered with a local Tanzanian radio station, Pangani FM, which aims to provide independent political news and socially progressive programs to people living in rural northeastern Tanzania. In 2018, Pangani FM acquired a new transmitter which would boost the reach of its signal to places that formerly lay beyond the station’s range. Importantly, natural variation in topography and distance from the radio tower meant that certain villages would receive Pangani FM signal for the first time while other nearby villages would remain just outside of range. This created the conditions for a so-called “natural experiment” in which arbitrary factors arising in nature would “treat” certain people with access to independent media but not others.

What sets this study apart from other natural experiments is that ours was planned ahead of time. This allowed us to conduct surveys comparing public opinion in soon-to-be treated and untreated villages before the transmitter was turned on, sidestepping the problem of having to merely assume pre-treatment similarities across the two sets of villages. Indeed, baseline surveys confirmed that the two sets of villages were similar across a range of outcomes. Having established that treated and untreated villages were comparable, Pangani FM turned on the transmitter, and we waited. After nearly two years, we returned to the villages to assess how attitudes had changed in the intervening period in places that had received the signal versus those that had not. Because we verified that these sets of villages were similar, to begin with, we could be sure that any differences that emerged after a year would be down to Pangani FM’s programming.

More independent media, more engaged and informed citizens

What did we find? First of all, villagers in places that received Pangani FM’s signal were indeed more likely to tune into the station. In untreated villages, almost no one said they listened to Pangani FM; in treated villages, nearly one in three people reported listening to the station. Many of these listeners switched from government stations to Pangani FM. This is an important finding in its own right. It suggests that local, independent outlets can successfully compete for listeners with government-controlled broadcasters that have dominated the airwaves for decades.

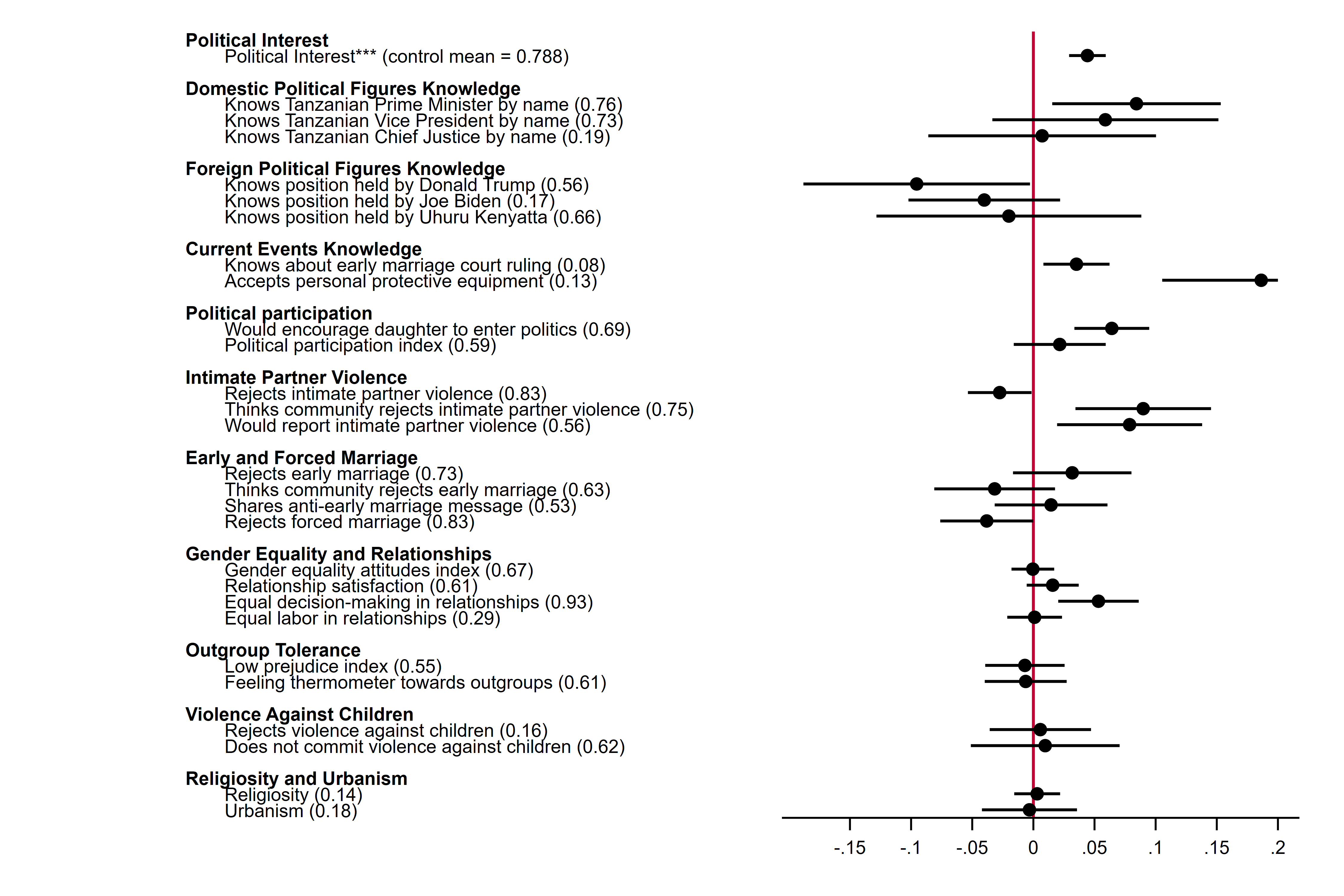

A year of access to Pangani FM had substantial effects on people’s interest in and knowledge about politics. Villagers that received Pangani FM became significantly more likely to say they were interested in politics compared to untreated villagers. Treated villagers also emerged with higher levels of civic knowledge and awareness of current events. Treated villagers were more likely to know who occupied key positions in government. They showed greater awareness of an important human rights-related ruling passed down by Tanzania’s high court. And they were more likely to accept face masks when offered by our surveyors, suggesting greater concern about the COVID-19 pandemic that broke out during the study period. This latter finding can be attributed to Pangani FM’s independent reporting on COVID-19 in the months before the government effectively banned media coverage of the virus.

While villagers who received Pangani FM didn’t report higher levels of voting than untreated villagers, they did become more supportive of women’s involvement in politics. Treated villagers were significantly more likely to say they would encourage their daughter or niece to run for political office, reflecting Pangani FM’s focus on gender equality in political life.

However, we didn’t find consistent evidence of changes in social attitudes. In some cases, access to Pangani FM appears to have made villagers more socially progressive — for example, by increasing willingness to report intimate partner violence and support for equal decision-making in relationships. However, we didn’t observe effects for other social attitudes, like rejection of forced marriage, rejection of corporal punishment for children, and tolerance for out-groups. The lack of consistent effects in this area might suggest that, although independent media can imbue listeners with greater political interest and knowledge, it may not lead to broader transformations in people’s social worldview.

Why the findings matter

An engaged, informed citizenry is crucial to a well-functioning democracy. Citizens can hardly be expected to participate in public life if they are uninterested in politics and don’t have access to politically-relevant information from unbiased sources. The fact that exposure to an independent news source made people more interested in and knowledgeable about politics points to the potential democratic dividend of allowing independent media outlets to operate, at a time when such outlets are spreading across the developing world. The findings also suggest that people are largely receptive to new political information, in contrast to more pessimistic views about citizens’ trust in journalists.

That said, political behavior and ingrained social attitudes appear harder to change. Perhaps another year of exposure to Pangani FM would have led to greater effects. The advantage of this sort of design is that researchers can return to the study area year after year to see if media effects grow larger over time.

Notes

Fig. 1: Map of Treatment and Control Villages in Natural Experiment.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “The Effects of Independent Local Radio on Tanzanian Public Opinion: Evidence from a Planned Natural Experiment” by Donald P. Green, Dylan W. Groves, Constantine Manda, Beatrice Montano, and Bardia Rahmani.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Donald P. Green is J.W. Burgess Professor of Political Science at Columbia University. He studies a wide array of topics: voting behavior, partisanship, mass media, hate crime, and research methods. Much of his current work uses field experimentation to study the ways in which political campaigns mobilize and persuade voters. For more information, visit his website.

Dylan W. Groves is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Government and Law at Lafayette College. His research focuses on comparative politics, media and politics, field experiments, environmental politics, and African politics. For more information, visit his website.

Constantine Manda is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Irvine. He studies religiosity in Africa and its political and economic implications. Using surveys and other methodologies, he’s uncovering the level of importance African citizens place on religion and the introduction and evolution of these beliefs. For more information, visit his website.

Beatrice Montano is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Columbia University. She works on the behavioral political economy of gender norms, combining formal theory and experimental research with fieldwork-based insights in the context of global development. For more information, visit her website.

Bardia Rahmani is a PhD student in Political Science specializing in comparative politics. His research interests include media persuasion, transitions to and from democracy, and the political economy of development with a regional focus on East Africa. For more information, visit his website.