What shapes individual support for public policies? Existing research has focused on factors such as self-interest, ideology or held values, and policy context when answering this question. Two important questions remain, however. First, how do different sources of economic insecurity interact in the formation of preferences for policies? While there has been some research on the effect of sociotropic and “pocketbook” risk in shaping policy preferences, the underlying mechanisms are still not well-studied. Second, policy context is recognized as a key factor in shaping support for public policy, but do individuals hold distinct preferences over different dimensions of policy design, and are preferences for those policy dimensions equally sensitive to insecurity?

We address these questions using an embedded survey experiment in the post-election round of the nationally-representative 2020 US Cooperative Congressional Election Study. To prime and manipulate individuals’ perceived exposure to labor market risk, each respondent received one of three vignettes: a control prompt (discussing the current US national unemployment rate), a higher insecurity treatment (discussing the same unemployment rate and projecting that it would increase in the future) or a lower insecurity treatment (same discussion and projecting that unemployment would decline in the future). Then, respondents were asked about their subjective evaluation of the likelihood that they would lose their job in the next 12 months.

Does Sociotropic Insecurity Increase Perceived Job Security? Yes.

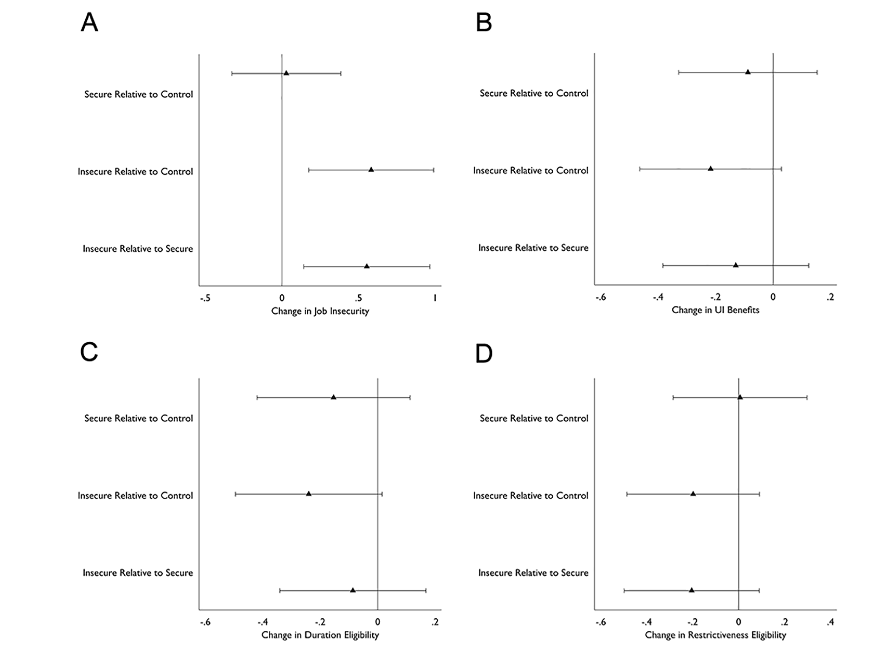

Our first result is that, not surprisingly, respondents who received the high insecurity prompt reported a statistically significant increase in perceived job insecurity compared to the control group (or the low insecurity treatment group). The difference between the high insecurity and control groups was about a 1/3 standard deviation increase in subjective job insecurity. This suggests that individuals exposed to greater macroeconomic insecurity (higher national unemployment rate in the future) perceive higher levels of subjective job insecurity than those exposed to rosier future unemployment outlooks or when future insecurity is not mentioned (the control group). As we expected, experimentally induced sociotropic insecurity significantly increased individuals’ subjective “pocketbook” job insecurity.

Does Economic Insecurity Shape Policy Preferences? No.

Our next result speaks to how insecurity shapes preferences for policy design and program generosity. Before asking respondents’ preferences, we informed them about key aspects of unemployment policy in the US: 1) each US state and territory provides insurance to those who are unemployed and meet eligibility criteria, 2) such benefits are typically paid out for a maximum of 26 weeks in most states, and 3) that benefits are typically equal to about 40% of someone’s prior weekly wage. Respectively, these points reflect the restrictive eligibility, duration of benefits, and benefit generosity of unemployment insurance in the US. Respondents were then asked if unemployment insurance were to be reformed, what changes they would prefer (more/less restrictive, higher/lower duration of benefits, and more/less generous replacement policies). Surprisingly, we found no evidence that changes in perceived job insecurity translate into any meaningful shifts in preferences for unemployment insurance generosity, duration eligibility, or restrictiveness eligibility. Against our expectations, the increased pocketbook insecurity induced by our experiment did not translate into any significant shifts in respondents’ preferences over the design or generosity of unemployment insurance.

A Puzzle: the Role of Partisanship

Why didn’t manipulated job insecurity shape respondents’ support for more (or less) generous insurance against unemployment? One reason may be partisanship. Democrats and independents were largely unaffected by the experimental treatments, but not Republicans. When presented with any information about future macroeconomic security (either the higher or lower insecurity treatments), Republicans reported significant reductions in their preferred policy generosity and duration. (Their preferences over strictness of eligibility criteria were unchanged).

These results raise a puzzle: why are Democrats’ and independents’ policy preferences unswayed by economic insecurity, and why do Republicans appear to double down on retrenchment of policy generosity when presented with any information (good or bad) about future sociotropic insecurity? On the one hand, left-leaning Democrats’ responses are consistent with a ceiling effect—their ex ante support for unemployment insurance is sufficiently high that experimentally induced insecurity had little influence. On the other hand, why would either an increase or a decrease in sociotropic insecurity (and induced pocketbook insecurity) prompt the same type of policy response from Republicans: to rollback benefit generosity and benefit duration?

What’s Next

In addition to raising this empirical puzzle, our findings point to a number of future research questions on the formation and determinants of public policy preferences, on how economic risk—both sociotropic and egotropic—shape those preferences, and, importantly, how partisanship or political ideology fit into these processes to moderate or mediate the effects of economic risk. Also, unemployment insurance is just one form of social insurance. It’s important to examine these questions in other policy areas like old age pensions, disability, or health. Especially in the current era of polarization, it will be an important task to understand how sociotropic risk, egotropic risk, and partisanship interact in shaping citizens’ support for public policy.

Notes

Evidence that priming about labor market risk increases self-perceived insecurity (A) but generates no changes in support for three policydimensions: unemployment insurance generosity (B), duration eligibility (C), restrictiveness eligibility (D). Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals shown.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Does Job Insecurity Shape Policy Preferences? An Experimental Manipulation of Labor Market Risk” by Mallory E. Compton and Andrew Q. Philips.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Mallory E. Compton is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Service & Administration at the Texas A&M University George Bush School of Government. She received her PhD in 2016 before holding a postdoctoral fellowship at the Utrecht University School of Governance, Netherlands. She has published more than a dozen journal articles and book chapters. Her co-edited book Great Policy Successes was published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Through her work, she studies the political prerequisites of bureaucratic success and performance in, with a focus on social policy feedback, preferences, and implementation. For more information, please visit her website.

Andrew Q. Philips is an associate professor and the Henry W. Ehrmann Professor in Law and Jurisprudence in the Department of Political Science at the University of Colorado Boulder, as well as a research fellow at the University of Colorado’s Institute of Behavioral Science. He received his PhD from Texas A&M University in 2017. Philips has published over two dozen articles on topics such as political economy, comparative politics, and gender and politics, and is a coauthor of a 2023 Cambridge University Press book on political budgeting. His research agenda also has a large methodological component, with interests in machine learning, time series, panel and compositional data. For more information, please visit his website.