Dictators make substantial efforts to shape their images in ways they perceive as favorable in service of their own political survival. For this purpose, public speeches are a crucial communication channel. Through speeches, autocrats communicate information to their audience in an attempt to motivate listeners to think and act in particular ways. Thus, in his recent annual address to the Federal Assembly on February 29, 2024, Vladimir Putin of Russia, while threatening the West with retaliation for its continuing military support of Ukraine, at the same time aimed to calm and coopt the public by also announcing the series of new national priority projects with significant budgetary outlays for social spending.

From existing research, we know that authoritarian communication strategies have important consequences in the sense that the topics emphasized, and the framings applied affect both elite and public perceptions and behavior. That is, how dictators speak have the potential to change their audience’s understanding of, say, the policy priorities and direction, as well as how strong and legitimate the regime and the ruler are.

However, apart from studies of particular countries at particular points in time, we know very little about what dictators typically emphasize in their communication with the public and what explains variation in the choice of communication strategy at different points in time and across countries.

Analyzing Thousands of Speeches by Dictators

To investigate this further, we have collected and analyzed a large text corpus of annual legislative addresses of 51 leaders in 12 post-Soviet, authoritarian countries and six unrecognized, non-democratic states from within the region during 1991–2019. We analyzed the content of these ‘state-of-the-Union’-like speeches with text-as-data methods and used statistical analysis to understand what prompts dictators to substitute between different rhetorical strategies.

In addition, we show the broader generalizability of our results by also examining the determinants of communicative strategies of a global sample of speeches by authoritarian leaders and foreign ministers in the UN General Assembly from 1971 to 2019 as well as a full sample of all of Russia’s president Vladimir Putin’s close to 6,000 public speeches and appearances.

What dictators talk about and when?

Specifically, we studied how contemporary dictators primarily rely on three rhetorical frames: one is related to economic performance legitimacy (termed responsiveness), another to patriotism broadly understood, and a third to instilling fear through intimidation.

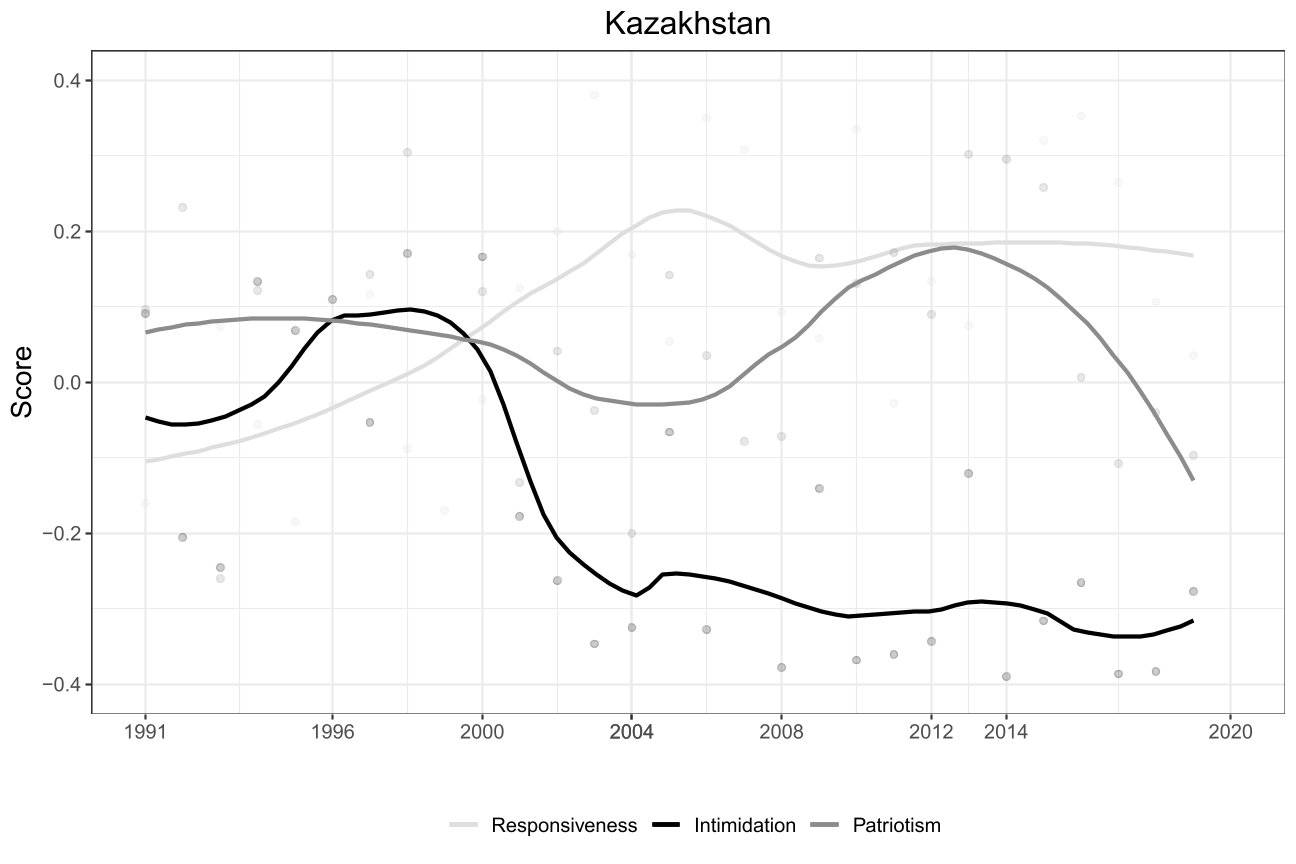

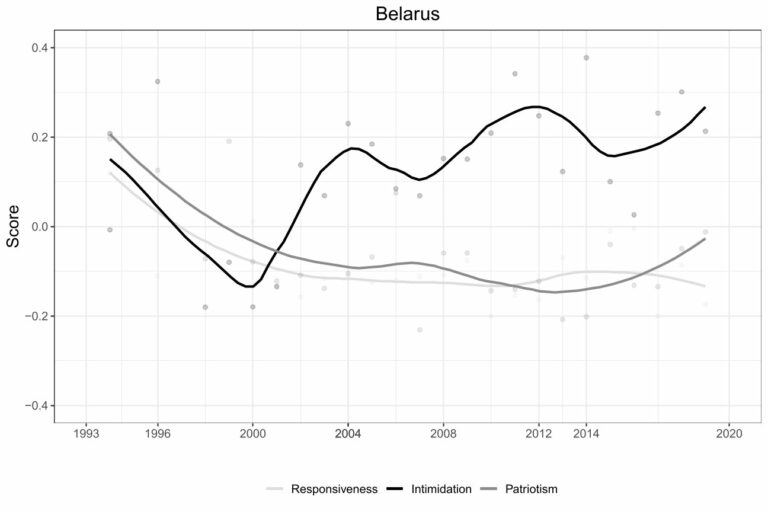

For illustration, Figures 1 and 2 show how the emphasis placed on each of these three strategies changes over time in speeches made by Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus and by Nursultan Nazarbaev of Kazakhstan. In most post-Soviet countries, presidential addresses are made in person to the national parliament and elites, broadcast live to the nation, and are strongly referenced in the media. In Kazakhstan and Belarus, for example, students and teachers were often required to watch and discuss a live broadcast of the president’s address.

In Kazakhstan, following a tumulous period characterized by negative, intimidating rhetoric in the mid-1990s when the president had the newly elected, intransigent parliament dismissed and then ruled by fiat, Nazarbaev’s rhetoric is then characterized by a strong emphasis on patriotism, and frequent references to economic performance and governmental responsiveness, throughout his tenure. In contrast, Lukashenko’s rhetoric has been very combative most of the time. As many other dictators, he attempted to bolster his defenses by using more bullying and intimidating language to dissuade opposition and instill fear and apathy in their audience, as Lukashenko did in his 2020 address: “These “puppeteers” will not succeed, but our people will suffer. … People have no shame. I’m not even talking about those whom I raised in my own hands. … We (the authorities and I, first of all, as the current President) will accept any decision, as long as you do not betray. Betrayal is not forgiven even in heaven. … Yes, while there is no hot war yet, no shooting, they haven’t pulled the trigger yet, there is an obvious attempt to organize a massacre in the center of Minsk…. We demand nothing extraordinary. Follow the law of the land, if you break it, our reaction will be instant, and rebuff will be most severe.”

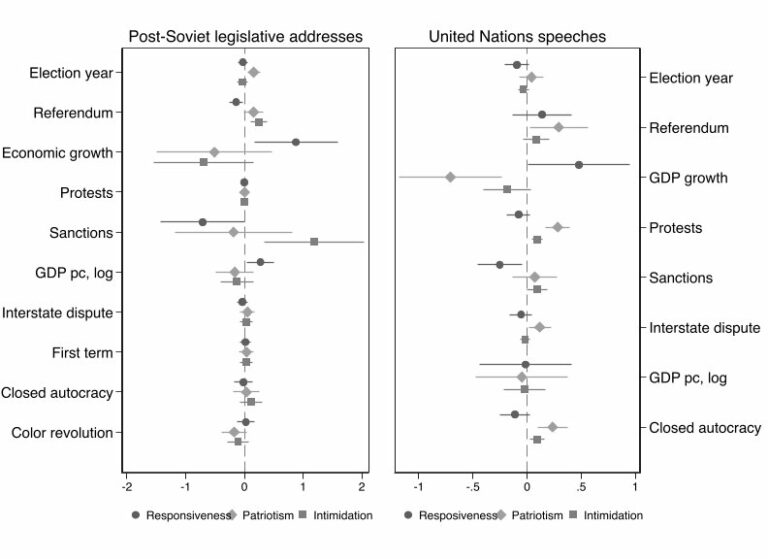

Clearly, authoritarian rulers’ communication patterns vary both across time and between countries. Next, we therefore tried to explain these patterns. Figure 3 shows the results estimated from the sample of post-Soviet annual addresses made by authoritarian leaders on the left and speeches made by leaders and foreign ministers of all authoritarian regimes during the United Nations General Debate, on the right.

More specifically, we find a number of interesting things. First, and most surprisingly, our analysis reveals that dictators use the communication strategy of speaking like performance-focused, responsive, would-be democrats much less than hitherto thought. While Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman have famously argued that contemporary dictators are ‘informational autocrats’ or ‘spin dictators’, whose rhetoric is captured by such characteristics, we show that this only applies when the economy is good and rulers can directly benefit from speaking about the socioeconomic conditions. When economic conditions turn for the worse, they instead come out as ‘intimidators,’ making overt threats and using aggressive language more generally.

Related, not even around elections do autocrats speak like democrats by exclusively attending to socioeconomic issues. Instead, they first and foremost appeal to voters with increased use of broad patriotic discourses that distract the electorate from pressing domestic issues. Patriotism, not issue responsiveness, is the primary electoral communication strategy in dictatorships today. Pacifying voters, not engaging with them seems to be the dictum for electoral autocrats.

Another interesting finding is that when autocracies are targeted with economic sanctions, leaders feel threatened and increase their reliance on the language of intimidation. That is, sanctions make autocrats strike chords of fear and oppression, essentially creating a more hostile and violence-prone domestic environment.

The same happens when dictators are challenged by popular protests. Again, we see that contemporary authoritarian rulers do not respond to such a crisis scenario by addressing issues of protesters or calling for national unity but instead fall back on well-known authoritarian tactics of oppression. Many dictators still follow old-fashioned styles it seems.

The Broader Implications

On a more abstract level, we show that it is the circumstances and challenges rulers face that dictate which rhetorical strategies they emphasize. That is, dictators’ communication patterns are highly strategic. Contemporary dictators do not use the same propaganda themes over and again but skillfully operate within a menu of communicative manipulation, emphasizing one strategy over another based on careful calculation of functional needs connected to their political survival.

Autocrats are not only ‘informational autocrats’ but also ‘patriotic autocrats’ and ‘intimidating autocrats’ when they have to. They may appear at one moment as responsive rulers, the next as old-fashioned brute oppressors, and the next again as community-invoking shepherds of the nation. This sharply contrasts with the conventional wisdom that authoritarian talk is cheap because autocrats are not accountable. Dictators’ speeches have much larger, often captive, audiences than those of their democratic peers; what is said, or not said, or even the expressed sentiment and tone often reveal important information about policy and politics. Thus, while autocrats are indeed less accountable and frequently deceive in public, we still need to pay serious attention to their speech because of what the latter can reveal.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Strategic Communication in Dictatorships: Performance, Patriotism, and Intimidation” by Alexander Baturo & Jakob Tolstrup.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Alexander Baturo is an Associate Professor in Government, Dublin City University, Ireland. He studies comparative democratization and authoritarian politics, as well as UN politics. His most recent book is The New Kremlinology: Understanding Regime Personalization in Russia (Oxford UP, 2021); you can find more here.

Jakob Tolstrup is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University, Denmark. He studies authoritarian politics and is a specialist in Russian and post-Soviet politics. You can find more information about his research here.