Local politicians often make decisions about building new housing projects. Even though towns need more housing to solve shortages and attract new residents, most people do not want new large housing projects in their neighborhood. This opposition stems from the negative impact on the physical living environment, changes in the composition of local residents and increased strain on public services like schools and healthcare. Our study looks at whether local politicians avoid placing new apartment buildings in the neighborhoods where they live.

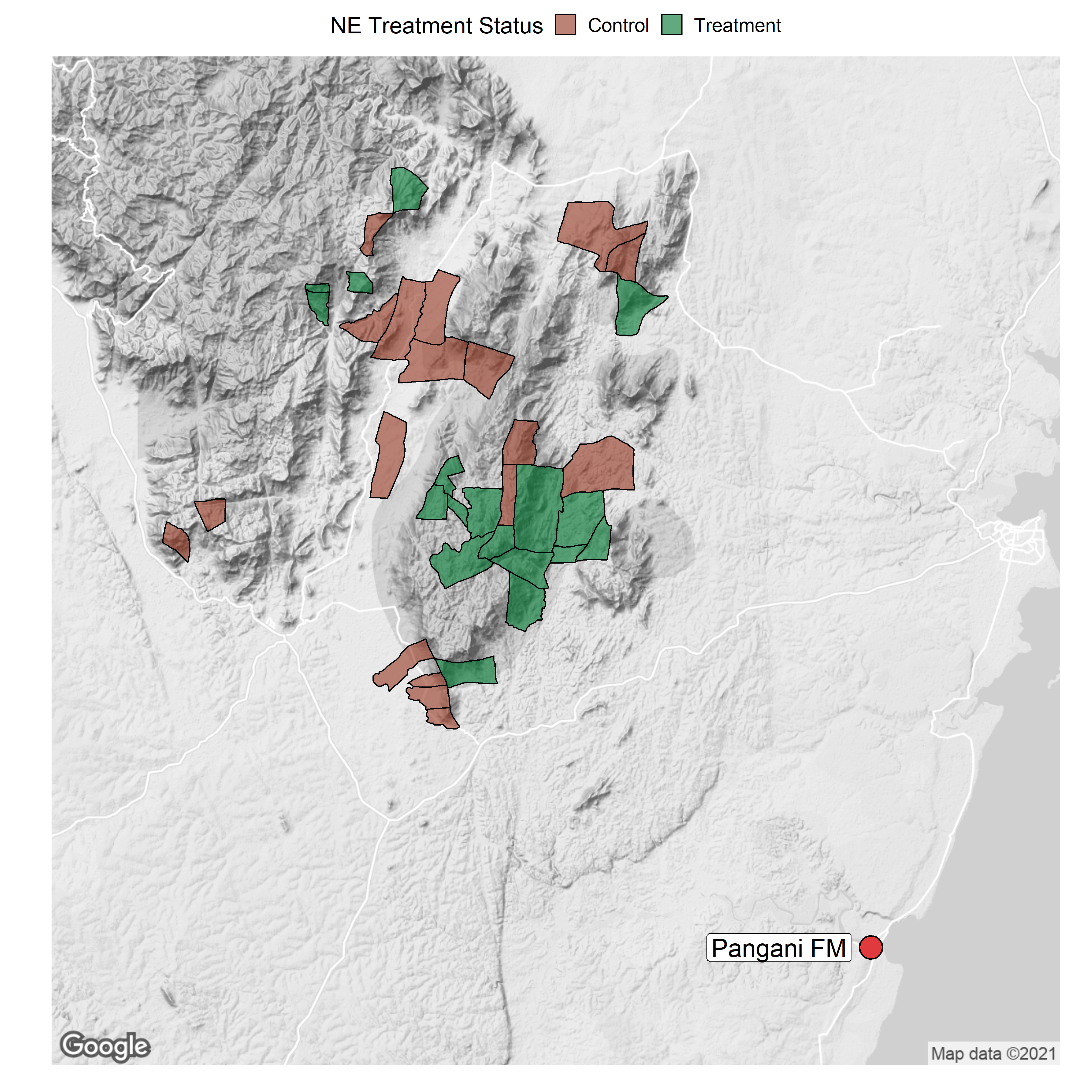

In Sweden, like in most other countries, local politicians must live in their municipality. Since most towns and cities constitute one big voting district, politicians do not have to live in different parts of the town. This article combines detailed data on the locations of politicians’ homes and a complete record of geo-coded building permits under these politicians’ control. Figure 1 illustrates where politicians and their voters live in a medium sized Swedish municipality.

The analysis looks at elections where a small proportion of votes separated the winning and losing bloc of political parties. We show that in places that had such close elections, the neighborhoods of winning and losing politicians are similar in terms of population, demographics, political participation, housing prices, and the types of buildings in the existing built environment. Our results show that the approval of new buildings shifts within the municipality when a new governing coalition takes power. After a close election, there are about 10% fewer permits for new multi-family buildings in the governing politicians’ home neighborhoods relative to the opposition politicians.

Why is there less new apartment construction in governing politicians’ own neighborhoods?

Voting patterns across parties or politicians do not appear to account for our results. Even if parties’ politicians tend to live in neighborhoods where the party receives more voters, this relationship cannot account for the findings about multi-family homes. The same is true for politicians’ preference votes. This indicates that politicians’ give preferential treatment to their own neighborhoods. Such preferential treatment could stem from a greater familiarity with the downsides of potential construction projects in “their own backyard”. A second reason could be politicians’ conscious or unconscious wishes to protect the value of their own property or avoid negative social reactions from neighbors and acquaintances. A third reason might be that residents’ local protests have more sway over politicians who live in the same neighborhood.

Implications for local inequality?

When politicians make decisions that favor their own neighborhoods, it can increase inequality in the community if politicians are overrepresented in certain areas. Our paper shows that local politicians often live in wealthier areas. These neighborhoods have more educated people, higher incomes, more homeowners, and fewer first-generation immigrants. Politicians from both left and center-right parties tend to live in more affluent neighborhoods than their voters. This suggests that politicians’ decisions to favor their own neighborhoods may increase inequality by benefitting already affluent areas within the municipality.

Note

Figure 1: Municipal councilors’ homes across neighborhoods in Partille municipality after the 2018 election. The map shows the location of politicians from the left and center-right blocs. The lines indicate electoral precincts, and the shaded colors show the balance of votes: red for left-wing and blue for center-right. The balance of votes is calculated based on the total number of votes going to either political bloc.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Politicians’ Neighborhoods: Where Do They Live, and Does It Matter?” by by Olle Folke, Linna Martén, Johanna Rickne, and Matz Dahlberg.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Olle Folke is Professor of Political Science at Uppsala University. He studies the selection of politicians from the population and consequences of such selection patterns. He also studies gender in the labor market with a focus on working conditions. You can find out more about his research here.

Linna Martén is a researcher at the Swedish Institute for Social Research at Stockholm University. Her research focuses on migration economics, labor economics, and political economics. You can find more information about her research here.

Johanna Rickne is Professor in Economics at the Swedish Institute for Social Research at Stockholm University. She studies political economics, gender economics, and labor economics. You can find more information on her personal webpage here.

Matz Dahlberg is Professor in Economics at Uppsala University and director of Urban Lab at Uppsala University. He works on questions related to urban and housing economics, public economics, and labor economics. For more information on his research, see here.