The increasing ethnic diversity of our democracies, as well as the pervasive ethnic/racial inequalities which structure them, have considerable implications for the political process. One such implication is the degree of electoral participation of ethnic minority groups relative to the White majority. Past research from several national contexts has pointed to an ethnic/racial gap, whereby ethnic minorities are less likely to be registered voters and less likely to turn out in elections. Classic political science perspectives attribute the majority-minority participation gap to differences in socioeconomic status between the two groups, emphasizing the role of income, social class, or education. Nonetheless, these factors have weak explanatory power in accounting for enduring ethnoracial disparities in registration and turnout.

In this paper, we shed new light on the ethnic/racial gap in voter registration by viewing it through the lens of geography. We argue that, given the substantial spatial concentration of ethnoracial minorities in disadvantaged residential areas across Western democracies, the characteristics of residential environments play a key role in the reduced electoral participation of ethnoracial minorities. We explore two main channels linking residential environments to voter registration.

The first channel is that living in a deprived neighborhood has deleterious consequences for political participation. Citizens living in poor areas generally have a lower capacity to collectively organize around common goals, such as addressing social problems like violence or disorder. Living in poor areas also often comes with negative social representations, which affects the self-worth of residents living there. Feelings of exclusion and stigma fuelled by discrimination in employment or housing markets create a sense of second-class citizenship. Research indicates that when individuals feel that they lack political influence or are personally discriminated against they are more likely to become politically disengaged. Hence, ethnoracial minorities living in poor areas may be less likely to register to vote.

The second channel is that the neighborhood ethnoracial composition promotes voter registration among discriminated ethnoracial minorities. In particular, living in areas with a strong co-ethnic presence may compensate for the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage. Recurrent ingroup contact among members of discriminated groups may cultivate a sense of collective ethnic identity and increase awareness of systemic discrimination against one’s own ethnic group, which has been found to boost participation. Moreover, ethnic minorities may become motivated to participate in politics in areas where they perceive their electoral influence to be high, while party elites are more likely to make systematic efforts to mobilize ethnic minorities in constituencies with a strong minority presence.

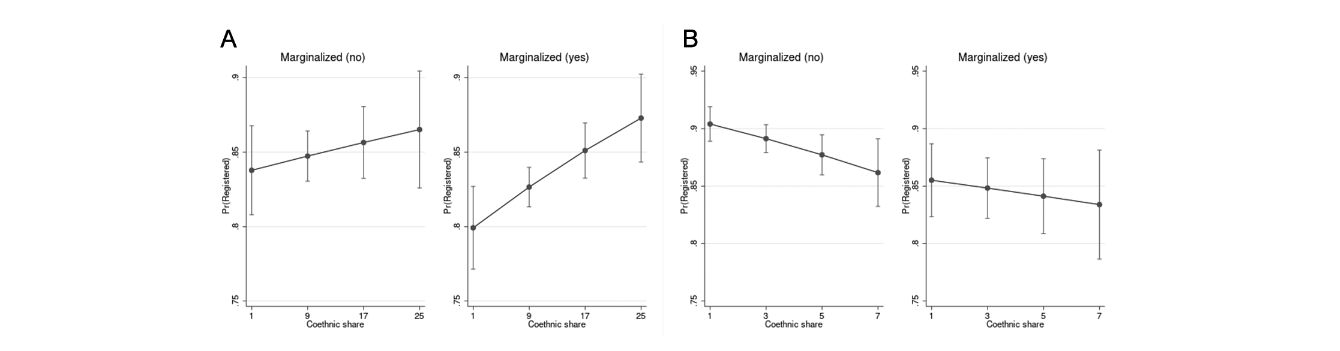

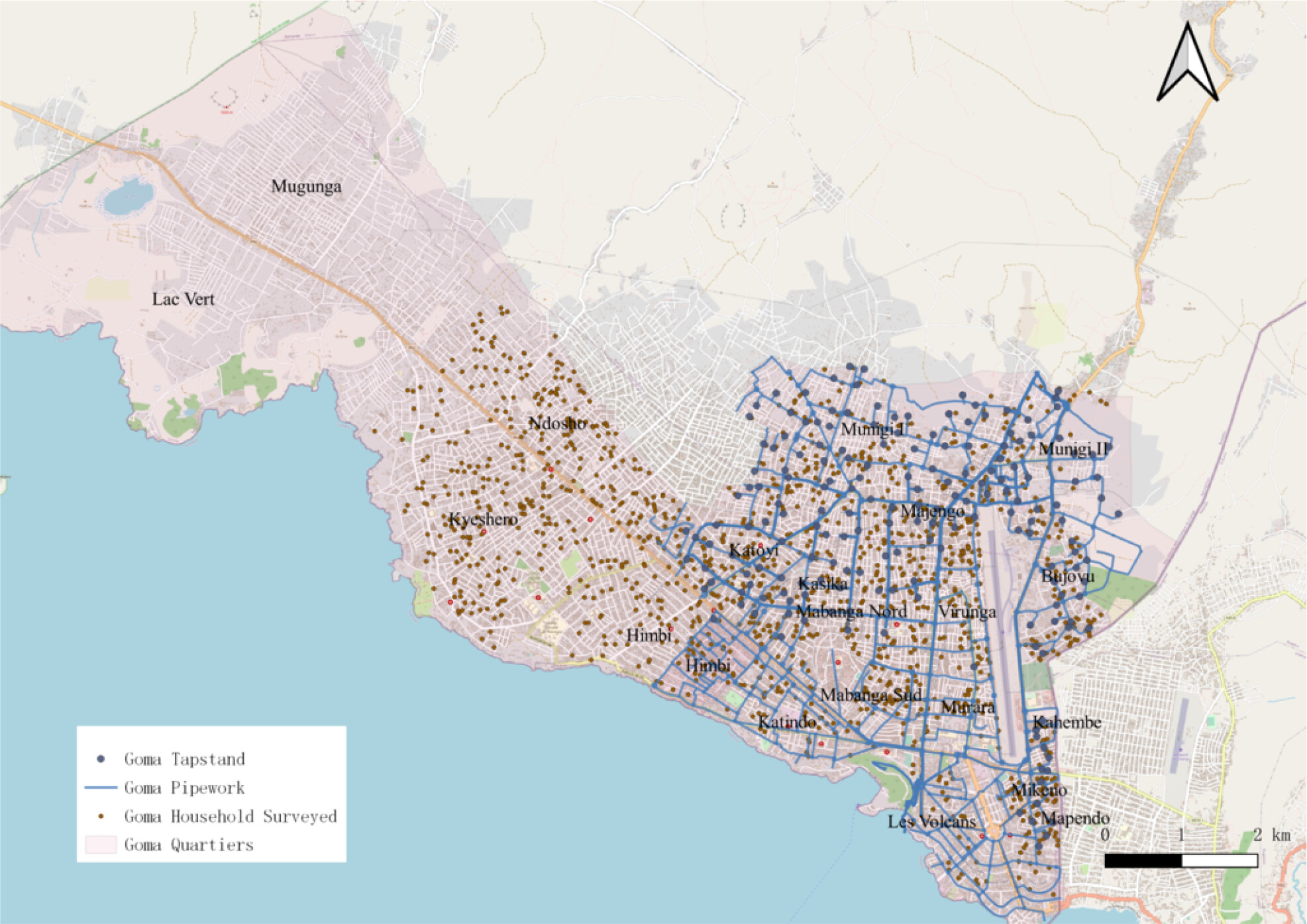

We test these two mechanisms drawing on the case of France, combining twenty years of linked census data, the Permanent Demographic Sample, with a large-N survey on immigrant integration, Trajectories and Origins (TeO). Despite a pervasive colorblind national rhetoric that downplays the importance of race/ethnicity as an organizing principle of social and political life, our data show that voter registration among ethnic minorities is between 13 and 24 percentage-points lower than among the French majority. Our findings provide evidence in favor of both spatial disadvantage and co-ethnic proximity effects. Living in a deprived neighborhood hinders the likelihood of registration among most citizens. Yet, spatial proximity to co-ethnics increases registration among citizens of Sub-Saharan, North African and other non-European origins – the most discriminated minorities in France. Complementary analysis from the TeO survey shows that awareness of discrimination and feelings of marginalization boost electoral registration and turnout among African-origin voters who live in co-ethnic dense neighborhoods. Collective consciousness of discrimination is hence the likely mobilizing factor in neighborhoods where African-origin groups are concentrated.

Our findings come with several implications for understanding political mobilization in France and potentially other contexts as well. They illustrate that despite the objective hurdles for participation posed by socioeconomic disadvantage and the place-based stigma experienced in disadvantaged spaces, there is significant potential for political mobilization as a possible defense against discrimination. The findings also suggest that discrimination does not necessarily dampen political mobilization – as prior studies have suggested – when discrimination is experienced collectively through spatial proximity. The enduring marginalization of minorities – via spatial segregation and widespread discrimination – may therefore not sideline them from the political process. These processes are instead likely to reinforce ethnic/racial polarization – not only in political participation, but also more broadly in political attitudes and voting behavior. Future research should continue to investigate the forms and mechanisms of these important forms of ethnic and racial political stratification.

Notes

Fig. 1: Registration by ethnoracial group, the neighborhood coethnic share, and marginalization: A, north and sub-Saharan African; B, southern European. Data source: Trajectories and Origins (2008)

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Do Neighborhoods Empower or Disenfranchise? Coethnic Concentration, Spatial Disadvantage, and Voter Registration in France” by Haley McAvay and Pavlos Vasilopoulos.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Haley McAvay is Senior Lecturer of Sociology at the University of York. Her research focuses on migration, ethnoracial inequality, spatial inequality, social stratification and discrimination.

Pavlos Vasilopoulos is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of York. His research interests include political psychology and political behavior.