International development actors–such as donor and lender governments, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), firms, and local governments–have strong incentives to cultivate favorable local and international reputations. A growing research agenda has examined whether and how individual actors can generate favorable overseas public opinion and “soft power” via aid and other forms of development capital. However, this research has largely neglected a basic feature of many overseas development projects: the involvement of multiple actors. Many international development projects involve multiple financiers and implementers, and multiactor projects have grown more ubiquitous and diverse following the rise of “emerging” donors and lenders such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye.

Attitudes Toward International Development Actors in the Democratic Republic of Congo

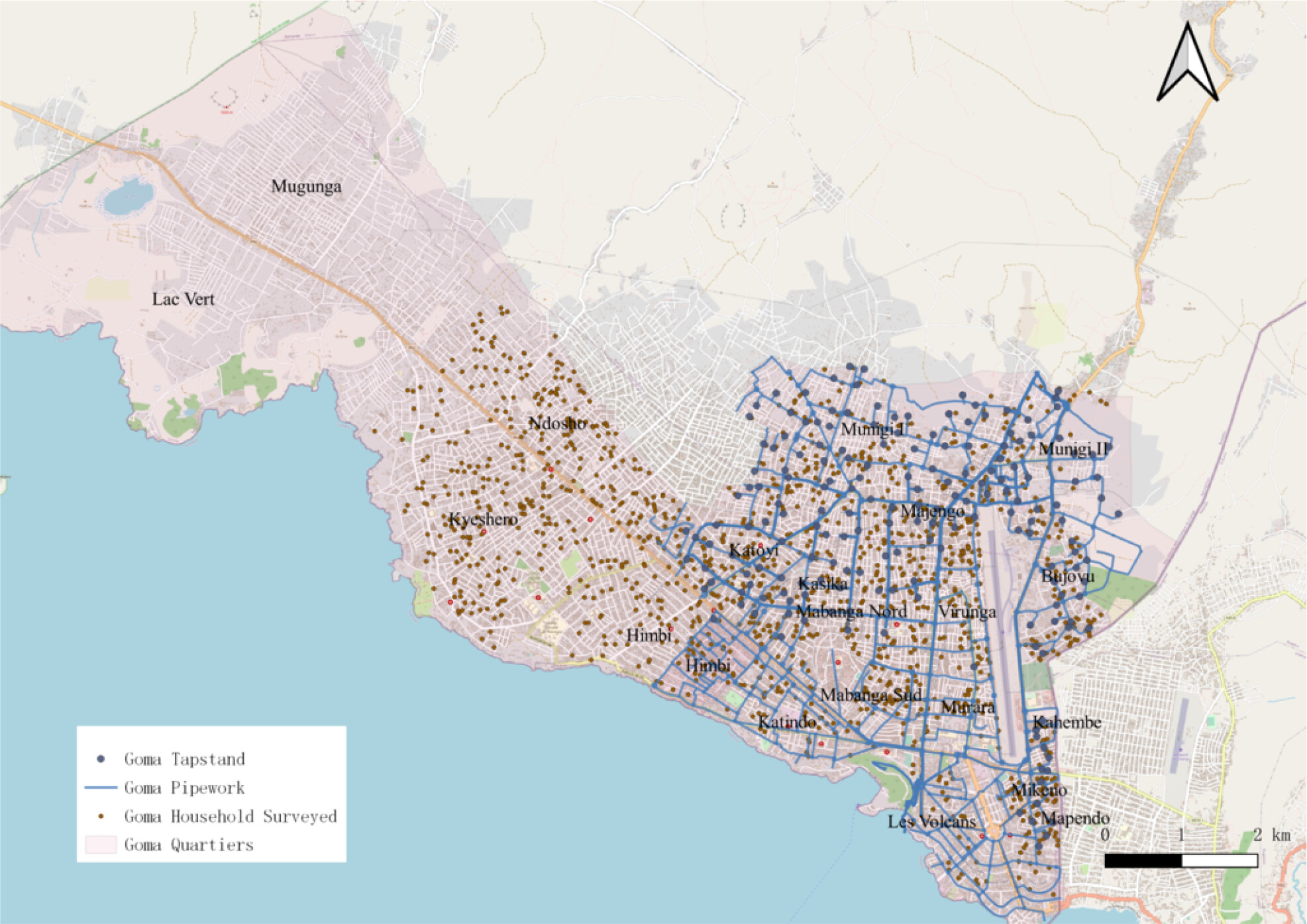

How do citizens in developing countries perceive international development projects involving multiple actors, and who receives credit or blame when positive or negative outcomes occur? Our recent study examines these questions by surveying public opinion in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a region with urgent development needs and a complex landscape of international development actors. In March 2021 we fielded a survey of over 2,500 households in Goma and Bukavu in Eastern DRC. The survey included an experimental portion in which respondents were informed about a recent water infrastructure project involving two foreign actors: a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) and a European-funded INGO. Some respondents were informed of both actors, while others were only informed of either the Chinese or European partner.

We purposefully selected these two actors because they have very different reputations and known comparative advantages. Chinese SOEs are often viewed as providing development “hardware” such as infrastructure with faster speed and less bureaucratic red tape, but are more commonly associated with labor and quality issues. In contrast, INGOs are often seen as “principled actors” in international development. Compared to SOEs, INGOs are seen as delivering projects more slowly but with higher quality and more stringent standards. This combination of actors was also broadly based on the Mercy Corps IMAGINE Program in the DRC, a real-world infrastructure project involving Chinese firms and a European-funded INGO that we analyzed in another recent article. As the below figure shows, we intentionally surveyed individuals residing in communities both closer to and further from IMAGINE locations to ensure that proximity to the project did not drive our results.

Complementary Partners and Asymmetric Attribution

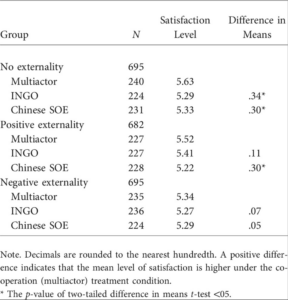

Our study found that respondents perceived a sense of complementarity between these two different actors. Across several tests, respondents were significantly more satisfied with projects involving both an INGO and a Chinese SOE, relative to projects involving only one of these actors. The below table provides the main results of our survey experiment, and shows that mean levels of satisfaction with the infrastructure project were higher among respondents who were informed of both SOE and INGO involvement.

To better understand and validate our survey results, our team conducted follow-up focus group discussions with over 140 survey respondents and a data quality audit. In focus group discussions, participants identified strengths of INGOs and Chinese SOEs and described them as complementary. For instance, focus group participants suggested there could be “strength in unity” between SOEs and INGOs collaborating on projects and that “each has their own field and there is always complementarity between people.” Respondents tended to see the INGO as adhering to stringent standards and the Chinese SOE as having faster implementation speed. They felt that combining these two attributes in a single project could potentially offer the best of both worlds.

However, despite perceived complementarity, we also found that Chinese companies and European INGOs did not necessarily accrue credit or blame equally within these partnerships. Instead, we observed “asymmetric attribution,” in which respondents were significantly more likely to attribute credit or blame to the INGO when a project produced positive or negative outcomes. Evidence from our survey and focus groups suggests that this result may be because people had higher ex-ante expectations for INGOs.

Multiactor Projects and the Future of International Development

Our study of collaboration between Chinese companies and European INGOs on overseas infrastructure is a first step toward understanding a growing but understudied phenomenon of multiactor international development projects. New constellations of international development stakeholders have emerged in recent years, particularly following the rise of “emerging” donors and lenders. For example, in addition to the Mercy Corps IMAGINE Program in the DRC, the International Committee of the Red Cross and inter-governmental organizations (IGOs) like the World Food Programme have cooperated or are considering cooperating with Chinese SOEs on infrastructure projects. The ubiquity of multiactor projects, particularly those involving actors with different development reputations, problematizes existing accounts of foreign aid and public opinion focused on straightforward scenarios involving attitudes toward individual donors and lenders.

Note

Fig. 1: Households Surveyed and IMAGINE Project Locations, Goma, North Kivu Province, DRC

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Complementary Partners? Attitudes toward Multiactor Development Projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo” by Austin Strange, Elizabeth Plantan, and Wendy Leutert.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Austin Strange is Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Hong Kong. He studies Chinese foreign policy, international political economy, and international development.

Elizabeth Plantan is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Stetson University. Her research focuses on state-society relations, environmental activism, and the comparative and international politics of China and Russia.

Wendy Leutert is Assistant Professor in the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies at Indiana University. Her research focuses on Chinese political economy, overseas investment, and international development.