The phrase “defund the police” entered the public imagination in summer 2020, as the nation became engulfed in social unrest as a result of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police. At the time, elected officials in cities around the country openly embraced the seeming popular idea of police reform in general, and decreasing or re-allocating police budgets specifically. But opinion polls quickly revealed high support for the police among the general public, and little apparent support for cutting local police budgets. Just a few months later, city politicians who previously supported the “defund” movement were backtracking, calling for more policing in the face of rising violent crime rates.

Did George Floyd’s murder actually have an effect on public support for local police funding? Such a question is difficult to study for several reasons. Before the events of 2020 made it a political issue, pollsters had rarely asked about support for police budgets on surveys. So while support may have seemed high on surveys in 2020, it is not clear what it would have been in the absence of Floyd’s murder and the subsequent unrest. Another reason this is hard to study is that those most affected by crime and police violence – poor and minority residents of large urban areas – are under-represented on national surveys.

In an article recently published in this journal, I address these challenges by looking to direct democracy referendums on police budgets in two large urban areas: East Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Fort Worth, Texas. For historical reasons, cities in these two states have the ability to levy separate taxes dedicated to funding sheriff (in Louisiana) or police (in Texas) departments. In both states, voters must regularly re-approve these taxes in elections: about every ten years in Louisiana, and about every five years in Texas. By 2020, these taxes funded millions of dollars in police funding in the two cities: 17% of the sheriff’s budget in East Baton Rouge and 27% of the police department budget in Fort Worth.

Also in 2020, both of these cities were due to hold referendums on their police taxes, and thus, on millions in police spending. While the referendums were originally scheduled for spring, the cities’ respective states each forced them to postpone the elections until July 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. While city officials did not anticipate Floyd’s murder and the subsequent unrest, the police funding referendums happened to occur just weeks afterward.

Using these referendums to study police funding attitudes comes with several advantages. First, because the referendums happened on a regular basis prior to 2020, it is possible to establish a baseline of what police funding support would be in the absence of Floyd’s murder. Second, unlike police reform referendums that were initiated and voted on after Floyd’s death, elites in these cities could not strategically influence whether measures got on the ballot or their content. Third, studying these elections allows us to zoom in on key demographics, including Black residents and those living in close proximity to local police violence, that are difficult to study using national surveys.

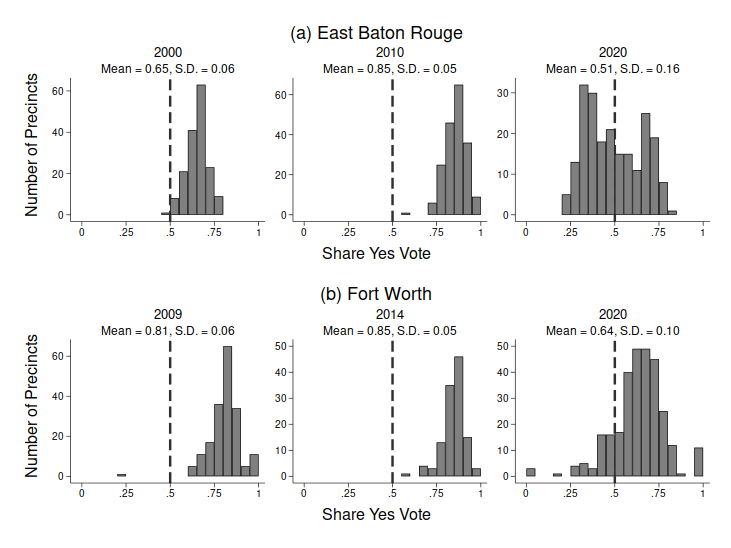

The figure below shows the number of precincts casting different levels of votes in favor of police funding by election in each city. Prior to 2020, support for police funding was almost universally high, with virtually no precincts casting a majority of their votes against. In 2020, in both cities, average support is lower, and there is a much greater spread in support, with many precincts voting against funding.

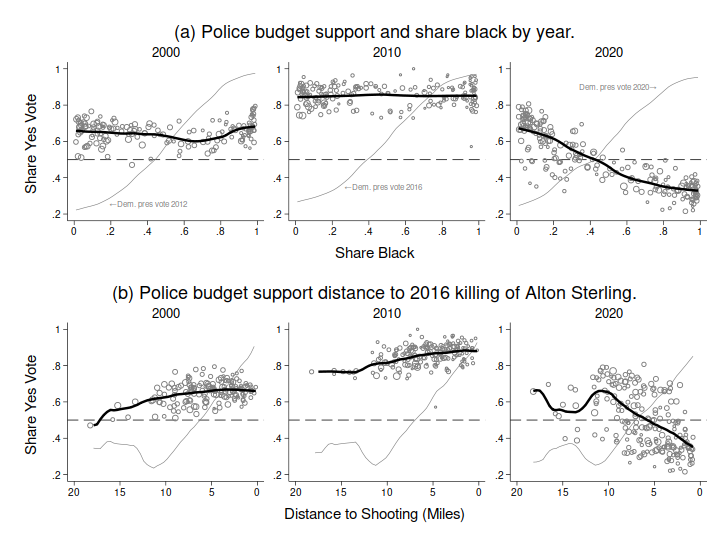

Which precincts became especially less likely to vote in favor of police funding? In the figure below, I focus on the results from East Baton Rouge. In 2000 and 2010, there was no relationship between the racial makeup of a precinct and support for police funding. In 2020, however, there is a sharp drop in support as the share of Black voters in a precinct increases. Similarly, support also drops in precincts that are closer in proximity to the 2016 killing Alton Sterling, which at the time spurred large local protests.

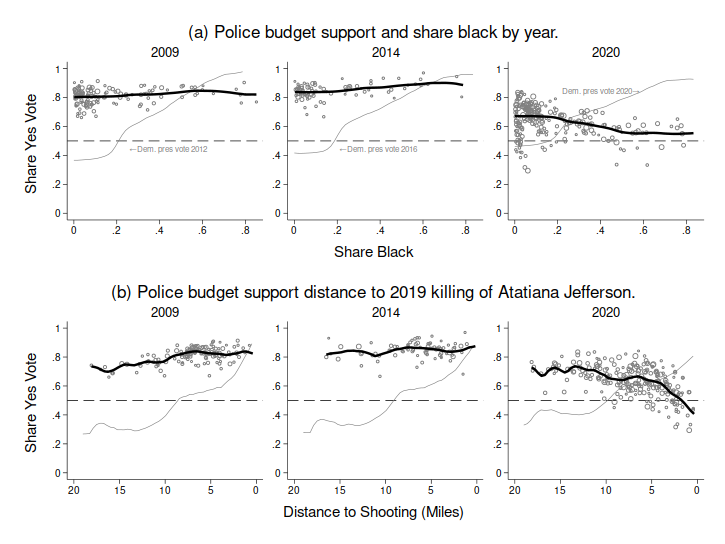

Of course, there were many other differences between 2020 and prior election years, and it is possible that these other differences – and not Floyd’s murder – explain the changes in voting patterns. As a check against this explanation, the gray lines in each graph show the relationship between the share voting for the Democratic presidential candidate and race/distance to the Sterling killing. Supporting the interpretation of the change in voting patterns being due to Floyd’s murder and not some confounding factor, these relationships are essentially the same before and after 2020.

In the figure below, I repeat the analysis for Fort Worth. Once again, there is no relationship between the share of Black residents and support for police funding in 2009 or 2014, but there is a negative relationship in 2020. Local police violence also matters: in 2020, support for funding declines with proximity to the most salient police killing in this city, that of Atatiana Jefferson in 2019.

Thus, at least in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s murder, these two cities both saw a sharp decline in support for police budgets, especially in Black neighborhoods and in areas in close proximity to past police violence. “Defund the police” was not simply a political slogan, but was genuinely embraced by some voters in a real election, and initial moves by officials in other cities to cut police budgets may have had significant public support. Future work, perhaps using the surge in police-related referendums since 2020, can investigate whether elite backtracking from “defund” was also consistent with public demands.

This blog piece is based on Michael Sances’ forthcoming The Journal of Politics article titled “Defund My Police? The Effect of George Floyd’s Murder on Support for Local Police Budgets”. The empirical analysis for the article has been successfully replicated by the JOP and all replication files are available in the JOP dataverse.

About the Author

Michael Sances studies representation and accountability through the lens of US state and local government. Recent research projects include the impact of the Affordable Care Act on political behavior, the causes and consequences of cities’ use of fines and fees as a revenue source, and spatial voting in mayoral elections. He teaches courses in American politics and research methods. He received his PhD in political science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2014, and has previously served as a postdoctoral scholar at Vanderbilt University and an Assistant Professor at the University of Memphis. Visit his webpage and follow him on Twitter: @mikesances.

Michael Sances studies representation and accountability through the lens of US state and local government. Recent research projects include the impact of the Affordable Care Act on political behavior, the causes and consequences of cities’ use of fines and fees as a revenue source, and spatial voting in mayoral elections. He teaches courses in American politics and research methods. He received his PhD in political science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2014, and has previously served as a postdoctoral scholar at Vanderbilt University and an Assistant Professor at the University of Memphis. Visit his webpage and follow him on Twitter: @mikesances.