Today, over half of the world’s population lives in cities. While developing countries remain predominantly rural, urbanization is expected to add 2.5 billion people to the global urban population by 2050, with 90% of this increase slated for Asia and Africa. India alone is expected to contribute 404 million individuals to this figure.

Where should these migrants live when they move to a city? Prices for urban housing can be out of reach for the rural poor, and many new arrivals live in informal settlements which can be plagued by problems of informality and poor service delivery. One particularly common government policy to address this problem is the subsidized sale of government-constructed homes to lower- middle class households. Such policies exist in India, Brazil, Uruguay, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, and elsewhere.

I study of the political effects of these common programs in Mumbai, India. Inspired by the work on NIMBYism among homeowners in the United States, I depart from frameworks of clientelism and patronage common to the study of India and measure effects not on voting, but everyday community-level demands to improve local public services. We might think of this type of behavior as civic participation.

The program I study is implemented in Mumbai by the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA). Because this program, like most others run by state housing boards, allocates apartments through a randomized lottery system, a study of winners and non-winning applicants is effectively a naturally occurring policy experiment. For the 2012 and 2014 lotteries, I procured from MHADA phone numbers and addresses for winners and a random sample of applicants. From an eligible sample constructed from this dataset, I randomly selected 500 households from each treatment condition to interview with the help of a Mumbai-based organization.

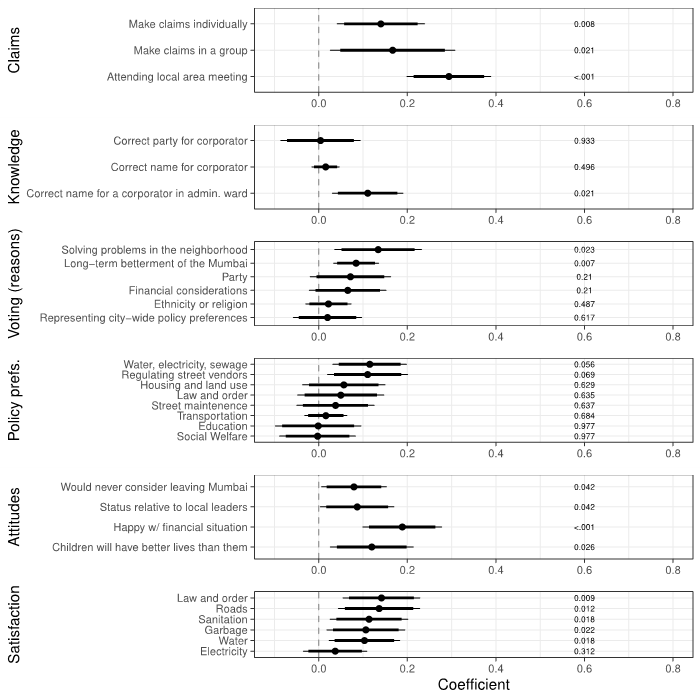

I estimate effects on local political participation as measured through this survey. I find that winners are about 29 percentage points (pp) more likely than non-winners to report attending local municipal meetings where they meet with representatives and discuss community improvements. They are also 11 pp more likely to report approaching bureaucrats and representatives to make complaints about community issues. This reported action is accompanied by demonstrated changes in knowledge, as winners are 11 pp more likely to be able to correctly name their local elected municipal officials.

This political participation is not confined only to those living in the new apartment buildings. Winners are not required to move to the homes, but can rent them out. Nevertheless, those who rent out the homes might want to participate in local politics to improve communities to increase the rental or resale values of the homes. Indeed, fifty-nine percent of landlords travel over an hour to the lottery homes to participate in local meetings in the communities in which they own homes but do not live. This effort suggests strong incentives for organizing separate from the effects of social pressure within a community.

Why do we observe these changes in behavior? On explanation is that winning the home may make recipients feel wealthier and increase their capacity to participate in local politics. Recent work in behavioral economics finds that the stress created by poverty can make it difficult to focus on long-term goals and lead to short-sighted behavior. Positive income shocks can increase psychological well-being, happiness, and time horizons, thereby reducing the cognitive or time- related cost of action. In line with this explanation, I estimate that winners are 19 percentage points more likely than non-winners to claim to be “happy” with the financial situation of the household. They are about 8 percentage points more likely than non-winners to respond that they “would never leave” when asked if would ever consider relocating from Mumbai, suggesting increased time horizons. A companion paper published in The Journal of Development Economics explores these household economic effects more fully.

I also argue that these changes in behavior are self-interested. As demonstrated by the literature on NIMBYism, subsidized homeownership can create interest groups of beneficiaries who are particularly motivated to work together to protect their benefits. To illustrate this mechanism, I also measure effects on stated motivations for voting in local elections. Relative to non- winners, I estimate that winners are 13 percentage points more likely to state neighborhood problems as a reported reason for voting, thus supporting increased interest in local problems as a mechanism for my findings. I also find changes in citizens’ policy preferences with respect to local government. I find an 11.5 pp increase in responses that the local government should prioritize improvements to water, sanitation, or electricity services, and an 11 pp increase in responses mentioning the importance of regulating street vendors. These results all suggest that protecting property values is a key motivation for the measured effects on local level political participation.

On the other hand, the results may be driven by the fact that program could generate new expectations of what government can or will provide, thereby further increasing the expected utility of action. Yet I measure no effect on policy preferences surrounding housing or social welfare, both of which the intervention provide.

Overall, I show that benefitting from this large intervention changes policy preferences and leads individuals to increase their reported participation in claim-making and knowledge of local government. I argue that these effects are driven by increased political capacity due to beneficiaries’ newfound wealth and increased self-efficacy. I further argue that this claim-making is motivated by a specific desire to protect the new wealth. Other wealth and income transfers that effectively boost beneficiaries’ political capacities and change their motivations possibly have similar effects.

Homeownership subsidies are wealth transfers, and wealth both confers power and motivates people to exercise power. As cities grow, these subsidies will only become more consequential because of both the growing potential for home value appreciation and the increasing number of people city politics will reach.

This blog piece is based on the article “Home-price subsidies increase local-level political participation in urban India” by Tanu Kumar, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, April 2022.

The empirical analysis of this article has been succesfully replicated by the Journal of Politics and replication materials are available at the The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the author

Tanu Kumar- William & Mary’s Global Research Institute

Tanu Kumar is a postdoctoral fellow at William & Mary’s Global Research Institute. She studies urban politics and political behavior, mainly in India. She seeks to understand the effects of policies aimed at managing rapid urban growth. She focuses on how policy both shapes, and is shaped by, the behavior of citizens and local-level officials. You can find further information regarding her research on her website and follow her on Twitter @tanu_kumar1.