Legislative committees have substantial power over the legislative process. Most enjoy negative agenda control—meaning that they can prevent any bill from moving to the floor and receiving a final vote—and nearly all have considerable authority to rewrite bills. Because committees are so influential to shaping policy and influencing outcomes, political scientists typically think of committee seats as strictly “good” and implicitly think that having more is always better for a legislative party than having less.

It may seem strange, then, that majority coalitions in legislatures do not just keep all committee seats for themselves. Why give minority members any access to influence at all?

Our article, “Allocating Costly Resources in Legislatures,” makes a point that most legislative research has looked past: committee service is time-consuming and this can make committee membership burdensome. Committees have lots of meetings (where absence is often punished) in which they sift through information, hold hearings, mark up bills, and take lots of votes. Some of this work can be passed off to staffers, but not all of it. While this work allows committee members to exert policy influence, it can often consume time they would prefer to spend elsewhere—like performing constituency service or fundraising.

Given that committee seats yield policy influence, but also consume a substantial amount of time and resources, understanding how majority coalitions allocate committee seats to majority and minority members is an important (and fun!) problem to solve. We argue that the majority should keep just enough committee seats for itself to be able to maintain control —that is, keep the minority from doing things the majority doesn’t like, such as attaching an unattractive amendment or preventing a majority-friendly bill from making it to a final passage vote—and give all remaining seats to the minority. We identify what we call a “minimum safe majority” as the number of seats the majority should keep for itself. This number is: a minimum majority of seats (e.g., 3 of 5, or, 7 of 13) plus or minus some contextual or institutional wiggle room. For example, in the case of contextual factors, we argue that as the majority becomes more ideologically diverse, it should require extra seats to counterbalance defections from the party-line.

The specific hypotheses that we derive from the argument are:

H1a: When the minimum safe majority coalition is large relative to the majority’s margin of chamber control, minority parties will be undercompensated in committee memberships.

H1b: When the minimum safe majority coalition is small relative to the majority’s margin of chamber control, minority parties will be overcompensated in committee memberships.

Note that by keeping just enough committee seats for itself to control the agenda and heaping all the excess committee seats on the minority, the majority gets to conserve the time and resources of its own members, allowing them more latitude for fundraising and constituency service, etc. As a bonus, the time and resources of minority members are spent down on extraneous committee assignments, potentially leaving them at electoral disadvantage.

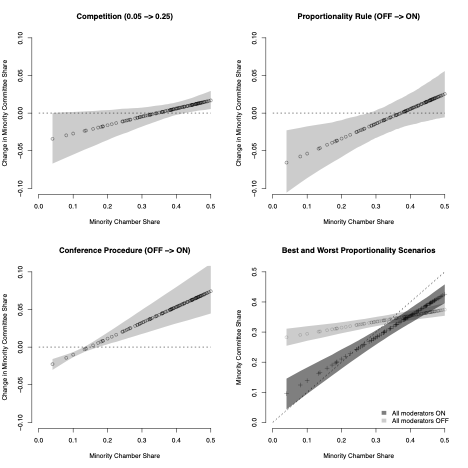

We also discuss reasons the majority may choose to be “fair” rather than exploit its seat assignment powers. A fair distribution of committee seats is defined as being (perfectly) proportional to overall chamber seat shares—e.g., if the minority controlled 45% of all legislative seats, fair committee divisions would allocate the minority 45% of committee seats. There are three moderators that we consider: “electoral competition”, “conference rules” (that mandate consultation between majority and minority leadership in committee seat assignments), “proportionality rules” (that dictate the share of committee seats allocated to each party).

We test our central hypotheses (and consider these moderators) by gathering data on the partisan allocation of committee seats in the 97-114th US Houses, 103-114th US Senates, and 96 state legislative chambers for the 2013-2014 session (we exclude Nebraska because it is technically nonpartisan and Connecticut because all standing committees are joint between the House and Senate).

As an aside: because our model yields sharp expectations for many parameter estimates—4 of 11 expectations are strictly directional (positive or negative), 7 of 11 are predicted to fall in a precise interval—our empirical tests are a little different from (and more fun than) the traditional assessment of directional probabilities and we hope you read the paper to check those out.

What do the data show? We find that committee assignments, in general, are consistent with our argument—the majority undercompensates the minority when margins are slim, but overburdens the minority more excessively as seat margins grow. The data do not support our expectation that ideological cohesiveness decreases the minimum safe majority, but do support our expectation that concentrated procedural power decreases the minimum safe majority. Further, the three factors we suggest should restrain the majority’s propensity to exploit its powers all exert the expected effect on seat allocations. The division is more “fair” when electoral competition is high, conference rules are present, and proportionality rules are present. Indeed, when all three are present, committee divisions are just about perfectly proportional. But, when all three are absent, committee divisions are almost entirely unresponsive to overall seat shares. These relationships are plotted in the figure below.

Dividing up committee seats in legislative bodies is process motivated by a complex of considerations, and our results reflect some of this complexity. However, our argument and our data demonstrate a clear—previously unappreciated—insight: committee seats are valuable, but can also be burdensome, and thus we should not expect legislative majorities to always take as many committee seats as they can get their hands on.

This blog piece is based on the article “Allocating Costly Resources in Legislatures” by Tessa Provins, Nate Monroe and David Fortunato, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 3.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Tessa Provins is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research focuses on the institutional design of legislatures and the effect of specific legislative features on the behavior of individual legislators and political parties. Her research also examines the role of institutional design on legislative process and policy outcomes. You can find more information here and follow her on Twitter: @TessaProvins

Nathan W. Monroe is Professor of Political Science and Tony Coelho Endowed Chair of Public Policy at the University of California, Merced, and the director of the Center for Analytic Political Engagement (CAPE). Much of his teaching and research focuses on legislative process–especially agenda setting–at the state, federal, and international level. His research has appeared in the leading journals and book presses in political science, as well as a number of interdisciplinary journals. You can find more information here.

David Fortunato is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the University of California, San Diego and an Associate Professor of International Economics, Government and Business at the Copenhagen Business School. He researches the structure of policymaking institutions and how they decisions made by both governments and voters. You can find more information here and follow him on Twitter: @DavidFortunato