Newspaper headlines at Waterloo station on July 7 2005. Image: Ellywa // wikimedia.org

It is well established that terrorist attacks change attitudes towards core freedoms. On average, we tend to become more supportive of harsh measures meant to reduce the terrorist threat. What is more contentious is when we switch attitudes, why do we do so, and who is more prone to give up freedoms for the sake of more security. Psychologists and social scientists advance some conjectures to explain our willingness to give up our liberties following a terrorist attack. For some, our reaction is driven by fear, which (irrationally) changes our appraisal of the risk of becoming, ourselves, the target of terrorism: We overreact. For others, we are induced by political elites, be they politicians or the media, to support illiberal policies: We are primed. And, of course, these conjectures are not mutually exclusive.

Can we discern which explanation is more likely? To do so perfectly would entail entering into the mind of each and every one of us to understand how we feel and think when a terrorist attack occurs. Yet, much can be learned from observing how fast we react to terrorism in historical occurrences of terrorist attacks. If we respond out of fear, we should expect our attitudes toward freedoms to change promptly after an attack. If we impulsively overreact to terrorism, we should expect stronger reactions closer to the time of the attack. If policymakers politicize fear and prime our responses, we should expect a delay in our attitudinal shifts in favour of harsh security measures.

Still, how can we observe when attitudes toward freedoms switch in the context of a terrorist attack? We do the following: We exploit the occurrence of the London bombings on July 5, 2005, during the fieldwork period of the British Social Attitudes Survey, carried out between May and November 2005.

To the young reader, we remind that what London experienced that day was one of the most dreadful terrorist attacks hitting the United Kingdom, which killed 52 people and injured 770 others. The bombings of the public transportation system in London were unexpected and sent shock waves not only domestically but to the whole international community.

The survey we use included questions asking people their support for very harsh measures intended to minimize the risk of future attacks. People were asked their views on policies allowing tapping their phones and opening their mail; having compulsory identity cards for all adults; banning certain peaceful protests and demonstrations; forbidding certain people from saying whatever they want in public. And not only that. The survey also asked people whether they agree with allowing suspects of terrorism to be detained without charge; to be denied a fair trial; to be electronically tagged; to be tortured.

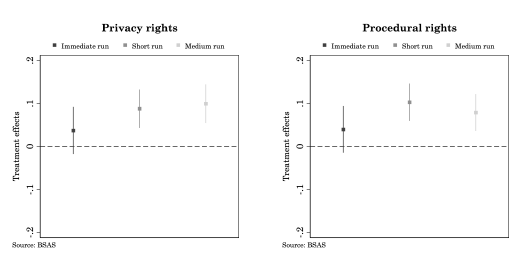

We compare how people responded to these questions before the attacks to the responses given after the attack. In addition, we track the changes in attitudes in three time periods, the immediate run (first week after the attack), the short run (first month minus the first week), and the medium run (second month until the end of the survey). Ideally, the immediate run would capture the impact of the terrorist shock alone, the short run would correspond to the shock coupled with external influences such as the media and politicians, and the medium run would recover reactions after respondents had time to process information. In short, we seek to adjudicate whether the public reacts impulsively, out of fear or irrationality, as some contend, or in a more “reasoned” fashion, as others claim.

The graphs below show our main findings. We separate the effect of the London bombings on privacy rights (banning protests and free speech, controlling e-mails, and imposing a compulsory ID card) and on procedural rights (arbitrary detention, torture, tagging suspects, denial of a free trial).

We observe no obvious reaction in the immediate run. People did not change their views in the first week after the attack, neither on rights meant to protect their privacy nor on rights meant to protect the rights of terrorist suspects. People did change their attitudes, and become more supportive of curtailing core civil liberties starting from the second week after the bombings (during the short run). Approval of these measures then stabilizes, at increased levels, in the medium run.

Not everyone changed their views on civil liberties though. Those with no university degree, and those who voted for the Conservative party in the previous national election, were more prone to demand harsher policies. Still, even these people did not immediately change attitudes. Their support for measures that severely cut back both their rights and the rights of suspects came with a delay, during the short run.

This delayed change of attitudes appears to run against the idea of an emotional and irrational public immediately willing to give up their freedoms out of fear. It took a week for people to change their views and to demand more security.

What can explain this delay?

We provide some evidence of a media effect. The changes in attitudes appear to coincide with the framing of the bombings by the media (especially tabloids): from a chronicled description of the attack in the first week to an emphasis on the perpetrators, their Islamic ties, and the measures needed to tackle the threat in the weeks that followed.

Understanding when and how shifts in public opinion occur is as urgent now as it was in 2005. Current national emergencies may have changed, but the incentives to use public attitudes to justify changes in policies that curtail liberties remain constant. Think of the “refugee crisis”, which led to sending asylum seekers to Rwanda or jailing them in “shelters” until their applications are reviewed. If our research is of any indication, media persuasion may be a driving force behind changes (or a lack thereof) in support for closing borders.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Wait and See? Public Opinion Dynamics after Terrorist Attacks” by Mariaelisa Epifanio, Marco Giani, and Ria Ivandic

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Mariaelisa Epifanio is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Politics, University of Liverpool. Her research focuses on counterterrorist regulation, terrorism and public opinion, and racial bias in law enforcement. You can find further information regarding her research here.

Marco Giani is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Economy, King’s College London. His research focuses on comparative politics and political economy. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter.

Ria Ivandic is a Lecturer at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford and Associate Researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research interests are in political behaviour, political economy of discrimination and the economics of crime. You can find further information regarding her research here and follow her on Twitter.