In March 2022, the Senate Judiciary Committee held confirmation hearings for Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson. As the first Black woman nominated to the United States Supreme Court (USSC), the confirmation proceedings were filled with references to the historic nature of her nomination and its meaning for the country. Judge Jackson, along with both Democrats and Republicans on the committee, spoke of her race, gender, and background as a public defender and Circuit Court judge, either underscoring her unique qualifications for the position, or suggesting she would be an overtly political and inappropriate justice. The attention to her individual characteristics is in tension with a longstanding body of work that sees judicial legitimacy as based in the institution and specific case outcomes rather than in the characteristics of judges. However, scholarship also tells us that the American public reacts to the identities of those in elected political office: people tend to prefer descriptive representatives (i.e. those who look like them) and White voters penalize candidates of color. In our recent JOP article, we ask: how do judges’ identities shape the American public’s trust in the courts?

First, it is important to recognize that we are in a politically polarized moment. Americans increasingly use their partisan and ideological identities to determine their in-groups and out-groups. This means that we tend to view our ideological kinfolk more positively and see those we disagree with as less trustworthy.

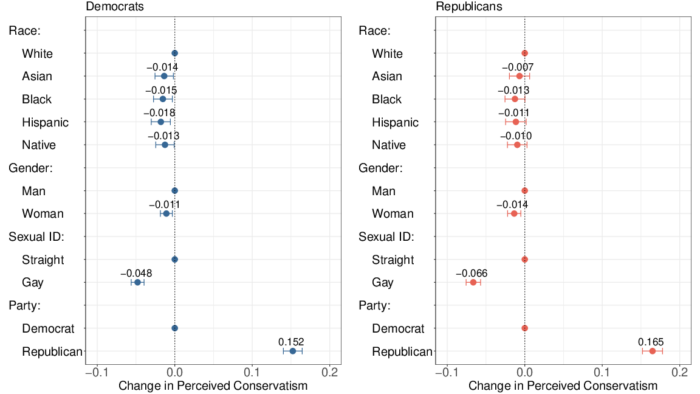

Second, political psychology research points to the way that people categorize identity groups ideologically. When people see identities, they tend to make assumptions about their ideological position. People arrange gays and lesbians to the left of heterosexuals, Democrats to the left of Republicans, and women to the left of men. We argue that the public uses judges’ identities to first, make inferences about their ideological placement, and second, determine their fairness, political impartiality, and trust in the Court broadly. We argue that rather than seeking identity congruence with judges (i.e. women supporting women judges), respondents seek ideological congruence—and they use identity categories (race, gender, sexuality, party) to do so.

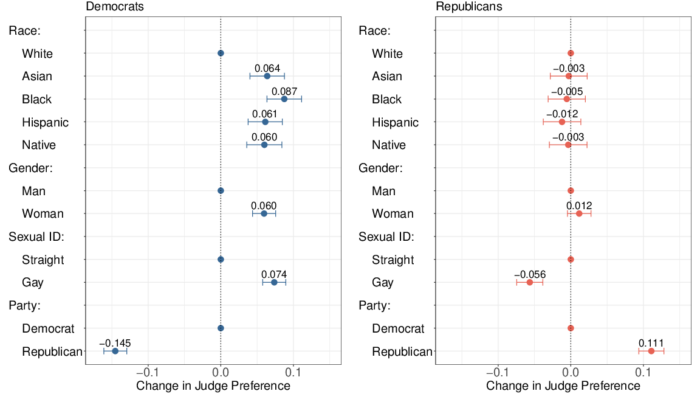

Together, we then expect that the public will perceive judges of color, women judges, and gay judges as more liberal than judges who are White, men, or straight. We further expect that Democrats will perceive judges who belong to marginalized race, gender, or sexual identity groups as better able to preside fairly, be more impartial, and would trust the USSC more if these judges were to join the bench. Our expectations for Republicans are the reverse: they will see judges with dominant identities as more trustworthy, impartial, and inspiring of trust in the Court broadly.

We fielded a conjoint experiment in October 2019 to over 4,000 Americans to test these expectations. We told respondents they would read about a case and consider potential judges who might be assigned to hear it. The case involved a fictional plaintiff suing her employer for discrimination. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of five types of discrimination: sex, racial, sexual orientation, gender identity, or religious. Then respondents saw pairs of judges and were asked which judge they trusted more to hear the case fairly and to briefly explain why. Respondents then placed judges on a seven-point scale from very liberal to very conservative, placed them on a seven-point scale from impartial to politically motivated, and indicated on a four-point scale how much they would trust the USSC if each judge joined the bench. Each judge’s profile listed seven randomized characteristics: race, gender, sexuality, partisanship, age, law school type and ranking, and previous job. Each respondent saw five judge pairings, meaning they evaluated ten potential judges. As the judges’ attributes are randomized, we can recover causal estimates of the different attribute values: e.g., what is the effect on trust of a judge being straight versus being gay?

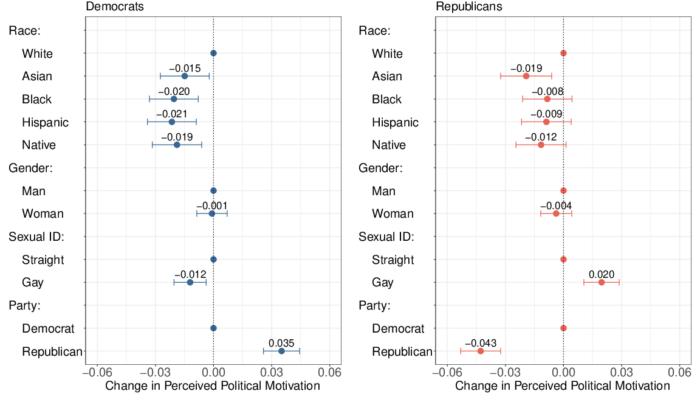

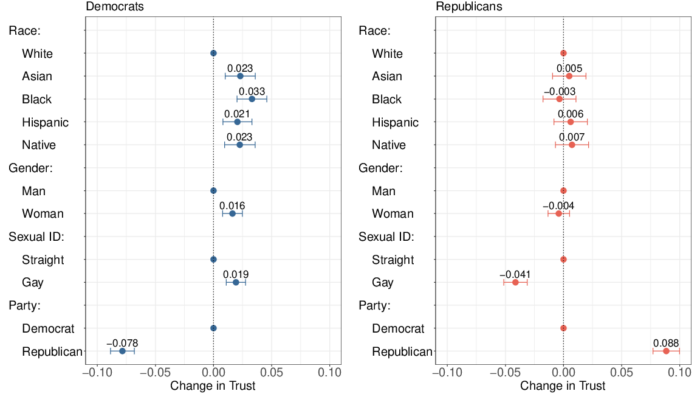

Our findings show both Democrats and Republicans perceive ideological differences by judges’ identities (Figure 1). This then maps onto their perception of individual judges as fair (Figure 2), impartial (Figure 3), and inspiring of trust in the USSC broadly (Figure 4): Democratic respondents prefer judges with marginalized racial, gender, and sexual identities while Republicans prefer those with dominant identities (although they are relatively indifferent to gender and race at least in our design where partisanship is known). The effects of judge sexuality are often the largest of any identity effects except partisanship, and Republican respondents are particularly distrustful of gay judges.

We also examine the qualitative data from respondents’ explanation of their choice. One-quarter of respondents mention a judge’s race, sexuality, or general minority status. Reflecting the partisan divergence in reactions to judges’ identities, some answers point to marginalized identities as a positive and others as a negative. For example, one respondent chose a judge “because he is gay and knows about discrimination” while another preferred a judge “because he is outside of being a lesbian [sic].” A few statements (3.9%) were explicitly intolerant; one person wrote they chose a judge because “she’s not a crusty old one,” while another stated “I don’t like gay people.” In short, respondents paid attention to judges’ identities and invoked them in their choices both in support of and in opposition to judges with marginalized identities.

Finally, we explored whether the type of discrimination in the case might matter. We found limited evidence of systematic differences across case type. When a judge’s marginalized identity was salient (e.g. gay judges presiding over a sexual orientation discrimination case), respondents were more likely to mention marginalized identities in the qualitative data. However, respondents did not consistently react more strongly to those same identities in the quantitative data.

Recent media coverage of the USSC highlights the deepening distrust in the institution and the justices. While distrust may stem from current scandals in financial disclosures or specific case outcomes, our work highlights an underappreciated mechanism for how the public determines their trust in courts. Despite claims from Justices that the courts are not political, it seems that the public perceives ideological differences in judges on the basis of their partisanship, but also their racial, gender, and sexual identities. Beyond simply assuming differences in judges’ ideology, Democrats and Republicans prefer judges who they see as ideological kinfolk.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “‘Because He Is Gay’: How Race, Gender, and Sexuality Shape Perceptions of Judicial Fairness” by Ana Bracic, Mackenzie Israel-Trummel, Tyler Johnson, and Kathleen Tipler.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Ana Bracic is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University. Her research focuses on questions of human rights, discrimination, the persistence of social exclusion, and ground-level effectiveness of human rights institutions, such as NGOs. Most of her research relies on lab-in-field and survey experiments. More information about her work, including her recent book Breaking the Exclusion Cycle: How to Promote Cooperation between Majority and Minority Ethnic Groups (OUP 2020, winner of Best Book published in 2020 from APSA Experimental Research Section), is available on her website.

Mackenzie Israel-Trummel is an Assistant Professor of Government at William & Mary. She studies American political behavior, and her interests include the politics of identity and the carceral state. More information about her work is available on her website and follow her on Twitter: @DrMackIT

Tyler Johnson is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oklahoma. His research agenda focuses on how information (be it media coverage, campaign advertising, or a candidate’s biography) affects attitudes toward political actors and issues. More information about his work is available on his faculty profile and follow him on Twitter: @tylerinoklahoma

Tyler Johnson is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oklahoma. His research agenda focuses on how information (be it media coverage, campaign advertising, or a candidate’s biography) affects attitudes toward political actors and issues. More information about his work is available on his faculty profile and follow him on Twitter: @tylerinoklahoma

Kathleen Tipler is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oklahoma. Her research interests are in the areas of American

constitutional politics, applied political theory, and law and society. She is particularly interested in questions of legitimacy, approaching those questions from the perspective of democratic theory. More information about her work is available on her faculty profile and follow her on Twitter: @ktipler47