Populist leaders are often seen as antagonistic to international organizations (IOs). They publicly criticize these institutions, withdraw funding from them, and sometimes even exit them. However, beneath the surface of apparent hostility lies a more nuanced relationship between populism and international cooperation. In our article, “Private Participation: How Populists Engage with International Organizations,” we uncover how populist leaders strategically interact with IOs behind closed doors.

Populism in Global Governance

Populists are known for their anti-elite, anti-foreign, and pro-sovereignty rhetoric. This stance often makes populists criticize multilateral cooperation; IOs are often thought of as being operated by and for the global elite with significant costs to national sovereignty. Thus, examples abound of populists attacking IOs, including Donald Trump’s criticisms of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and World Health Organization (WHO), as well as Viktor Orban’s disparagement of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Our research provides a more nuanced picture of how populists approach IOs. We show that populists engage with IOs discreetly—away from public view—to reap the benefits of multilateral cooperation without sparking domestic backlash. Such private participation allows populists to maintain the appearance of defiance while still leveraging the resources and support that IOs offer.

Evidence from the IMF

To explore private engagement, we examined archival data from the IMF. Specifically, we analyzed around 55,000 confidential statements made by IMF Executive Directors in meetings of the Fund’s Executive Board from 1987 to 2017. These statements, which are only declassified after several years, provide a window into the behind-the-scenes negotiations and positions of member states (see Table 1).

Controlling for a range of relevant factors, our findings show that populist-led countries submit approximately 80% more of these statements than non-populist countries, indicating a higher level of private engagement by populists, contrary to their public disdain for the institution.

Furthermore, sentiment analysis reveals that the tone of these private statements is as positive as those from non-populist countries. Such positivity suggests that populists, despite their public criticisms, engage constructively with the IMF to secure economic assistance and technical advice. This engagement helps them avoid the reputational and material costs of overt participation while still benefiting from the IMF’s resources and expertise.

We also show that while populists readily utilize private channels, they are less likely to engage IOs in public—such as through structural adjustment programs at the IMF—because the costs of doing so are significantly higher than for non-populists.

Implications for Global Governance

Our study offers new insights into the complex relationship between populist leaders and IOs. It challenges the conventional wisdom that populists are merely hostile to global governance. Instead, our research shows that populists strategically choose private over public engagement to maximize benefits while minimizing domestic political costs. In other words, populists balance their need for IO support with their pro-sovereignty, anti-elite political rhetoric.

This dual strategy of populist leaders—public defiance coupled with private participation—has significant implications for the future of international cooperation. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for policymakers and scholars aiming to navigate the challenges posed by populism as populist leaders and candidates accrue power across the globe while contesting the extant global order.

Note

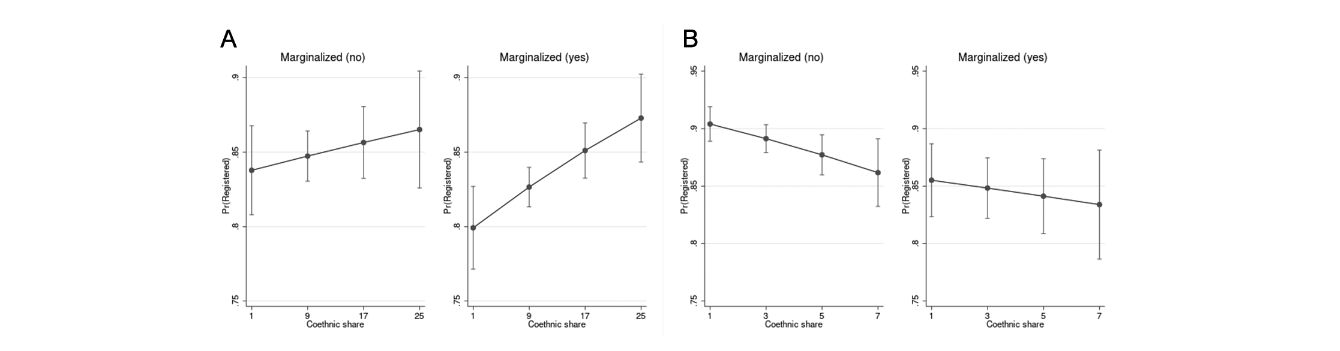

Tab. 1: Illustrative Grays.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Private Participation: How Populists Engage with International Organizations” by Allison Carnegie, Richard Clark, and Ayse Kaya

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Allison Carnegie is a Professor of Political Science at Columbia University.

Richard Clark is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame.

Ayse Kaya is a Professor of Political Science at Swarthmore College.