In a new paper titled “Can the Party in Power Systematically Win a Majority in Close Legislative Elections? Evidence from U.S. State Assemblies,” Dahyeon Jeong and Ajay Shenoy find evidence that parties can systematically win a slender majority of seats in close legislative elections, at the cost of winning fewer seats.

Most states pass new redistricting plans every 10 years as regular legislation, giving the party with a majority in the state legislature control—or at least a veto—over congressional redistricting. Given the high stakes of congressional elections, parties have an incentive to hold the majority in the year they draw congressional boundaries. However, election results are ultimately decided by voters. Can the ruling party nevertheless all but ensure it wins just above 50% of the seats in the crucial state assembly election that determines control of redistricting?

Winning just above 50% of the seats depends on any number of factors. But it should be close to the probability of winning just below 50% of the seats because the party cannot predict outcomes of all races and it may lose (or win) seats that it expected to win (or lose). For example, consider the following numerical example. Suppose a legislature has 99 seats. If the majority party wins each seat with a 55 percent probability it would win 50 seats with a 5.4 percent probability, similar to the 4.4 percent probability of winning 49 seats. Even if it channeled its resources towards winning only the most promising 55 seats, each with a 90 percent probability, it would have an 18 percent chance of winning 50 seats and a 16.5 percent chance of winning 49 seats.

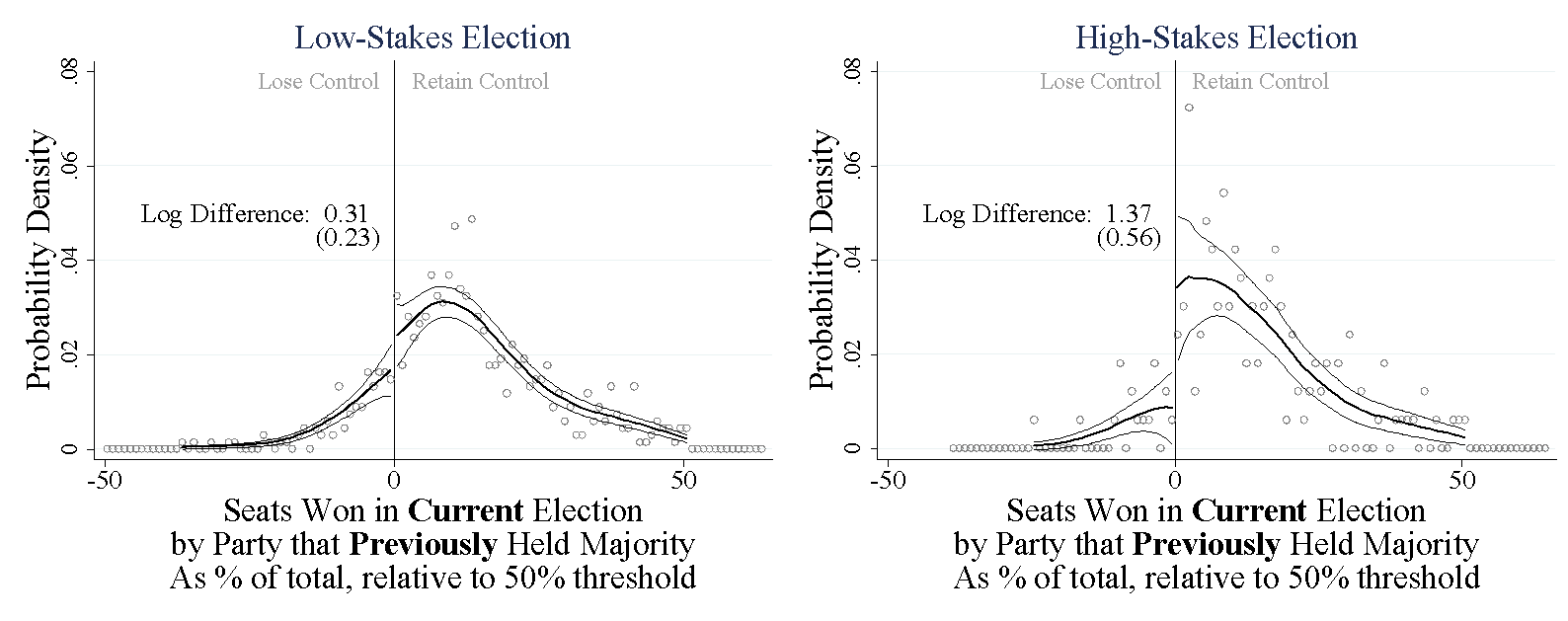

Using party composition data in the lower house of the state legislature for elections from the 1970-2010 redistricting cycles, this is precisely what we find for most elections. Figure 1 plots the density of the seat share won by the party that entered the election holding the majority. During elections that do not determine control of redistricting (call them “low-stakes elections”), the probability of winning a bare majority is not different from the probability of barely losing the majority (the left-hand panel). But in “high stakes elections”—elections that decide which party controls Congressional redistricting—the party that entered the election as a majority is 4 times as likely to barely retain the majority as to barely lose it.

What is surprising is not that the majority party is able to retain its majority, but that it wins just above 50% of the seats, a slim majority that is only possible if the party can predict the results of most races with certainty. The fact that this pattern is not found for elections that do not determine control of redistricting suggests that the pattern is likely not a natural feature of elections but the result of a conscious effort by political parties—a phenomenon we call precise control.

Figure 1. Probability Distribution: The Majority Party is Far More Likely

to Barely Win than Barely Lose a High-Stakes Election

How can the majority party ensure it barely retains its majority when the outcomes of elections are ultimately decided by voters?

This asymmetric finding between typical elections and high-stakes elections is supported by evidence that parties switch their objective from seat maximization in usual times to majority-seeking in elections that determine control of redistricting. James Snyder theorized in his 1989 paper that when a party’s objective is to maximize the probability of winning a majority (as opposed to maximizing the number of seats won), it focuses on channeling more resources towards holding safe districts.

We show that in high-stakes elections, parties change their spending to be consistent with majority-seeking tactics. Parties spend more; they concentrate their spending in key races, and they discourage incumbents from retiring. Since these tactics are inherently defensive, they are disproportionately more effective for the party that already holds a majority, potentially explaining why the majority party can exert precise control despite the opposition’s countermeasures.

Why should scholars and voters care if a state’s majority party can exert precise control? Let’s return to the example of the legislature with 99 seats. If the probability of winning 50 seats—a bare majority—is drastically higher than the probability of winning 49 seats, it suggests the party can systematically limit its losses to just retain its majority. The party must rank all races and focus its resources on the 50 most promising, tilting the odds in each race until it is all but guaranteed the seat is retained. As the 55-seat example shows, precise control is not possible if the probability of winning each seat is merely very high—it must be close to 1. Precise control is unsettling because its presence implies there is almost no chance the majority party will lose any of the seats it needs to win.

Precise control may increasingly have implications for policy as well. In the past, parties could not expect to pass substantive legislation with only a bare majority. But as state parties grow evermore ideologically polarized, party-line votes may become common. Eventually, a bare majority may suffice to pass bills on taxes or health care, making precise control increasingly attractive and of immediate relevance to policy.

This blog piece is based on the article “Can the Party in Power Systematically Win a Majority in Close Legislative Elections? Evidence from U.S. State Assemblies” by Dahyeon Jeong and Ajay Shenoy, The Journal of Politics, volume 84, number 1, January 2022.

About the Authors

Dr. Ajay Shenoy is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He studies political institutions in developing and fragile democracies. His other research interests include production and market imperfections in developing countries. He received his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Michigan and his B.A. in mathematics and political science from the University of Connecticut. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @AjaycencyMatrix

Dr. Ajay Shenoy is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He studies political institutions in developing and fragile democracies. His other research interests include production and market imperfections in developing countries. He received his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Michigan and his B.A. in mathematics and political science from the University of Connecticut. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @AjaycencyMatrix

Dahyeon (DJ) Jeong is an Economist in the Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) unit at the World Bank. His research interests include agriculture, labor, social protection, and political economy. He conducts policy-oriented research using experimental methods in developing countries. He received a Master of Public Administration from Cornell University and a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of California, Santa Cruz. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @dahyeon_jeong

Dahyeon (DJ) Jeong is an Economist in the Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) unit at the World Bank. His research interests include agriculture, labor, social protection, and political economy. He conducts policy-oriented research using experimental methods in developing countries. He received a Master of Public Administration from Cornell University and a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of California, Santa Cruz. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @dahyeon_jeong