The relationship between the public and elected leaders is among the most studied phenomena in political science. Executives undoubtedly prize and prioritize their maintenance of power, implying that they undoubtedly heed public opinion that determines it.

When it comes to foreign policy, though, a wealth of research suggests that public attention is limited and short-lived. As a result, mass opinions on foreign affairs are less clear and stable. One possible inference is that presidents can dismiss them more than on domestic affairs, although this bears some risk in the event of a foreign policy flub. Another possibility is that leaders can shape them to their advantage.

Here again, loads of literature demonstrates that executives aim to lead public opinion whenever and however they can. They watch polls to gauge the public mood, run their own polls to test political and rhetorical strategies, time communications to mute or amplify messages, curate media interfaces to convey key messages, and more. Missing among these efforts is a systematic examination of what exactly they say.

Framing Public Opinion

Using framing theory, which explains how speakers bound and define issues for an audience, I examine how U.S. presidents justify the use of military force to the public. Military mobilizations are key occasions when the public perks up and seeks information on foreign affairs. They imply a new crisis or major stage of an ongoing conflict, which coincide with presidential information advantages. Altogether, they are moments when the president has the prerogative to speak, and the public is intensely incentivized to listen.

Executives explain their reasons to the public in ways that maximize public buy-in. When the rationale for military force sits well with the domestic population, they tell it like it is. When the primary motivation is less savory to mass audiences, presidents downplay, spin, or entirely neglect it. Ultimately, they define what that military intervention is and is not about at the outset, structuring public attitudes and subsequent debates in one powerful speech.

Popular, Therefore Honest, Justifications

Ample previous research catalogs the conditions under which the public supports war. When it is perceived as legitimate, right, and achievable, voters are more prone to endorse the use of force. Knowing this, presidents will accurately articulate these reasons any time they obtain because they elicit the desired support without risks of backlash over misinformation or manipulation.

So what are legitimate, right military missions? I argue that the public is likely to support strategic and humanitarian force and counterterrorism. Strategic interventions are mounted to maintain power balances, stability, and a favorable world order. People perceive them as salient and consequential for national interests, especially in regions of geopolitical interest.

Publics widely support humanitarian force that alleviates human suffering, especially of the innocent and defenseless. All else equal, most people have a moral compulsion and compassion to end mass misery, whether caused by nature or man. Such missions are seemingly simple and easy to understand. They’re also hard to criticize, making elite bipartisan support more likely.

Last, American public awareness of terrorism skyrocketed after 9/11 and remains consistently salient. Feeling vulnerable to this threat, citizens want to see counterterror efforts from the government. Media favor reporting on terror attacks, reinforcing the public’s sense of threat and mobilizing support for the president’s counterterror agenda.

In sum, when military force is dispatched in response to terrorism, humanitarian relief, or strategic challenges, the public is more prone to back it and the president. Therefore, presidents have clear incentives to justify these instances to the public honestly.

Unpopular, Therefore Censored, Justifications

The public is less amenable to economic and territorial rationales for war. Economically motivated uses of military force appear disproportionate, unnecessary escalations from economic or legal solutions. Activating the military option, then, might also signal greed or interest group meddling that smacks of corruption.

Territorial military interventions are globally common, but for several reasons I argue that the American public doesn’t prefer them. Territorial wars tend to be the most escalatory, severe, and recurring, requiring intensive commitments during and after fighting. Oftentimes, it’s not clear which side is “right” in their claims on the territory. Norms of sovereignty and democratic principles of property rights might also condition the public to see them as less legitimate.

Nonetheless, at times leaders are compelled to activate the use of force for these aims. Rather than facing public disapproval with transparent justifications, rather than attempting to explain the complex reasons behind these choices, I argue that presidents sidestep both by strategically framing them. This might mean a mere deemphasis, highlighting more popular albeit secondary motivations. But it might also mean censoring them, laundering them through popular justifications instead.

Examining What Presidents Say

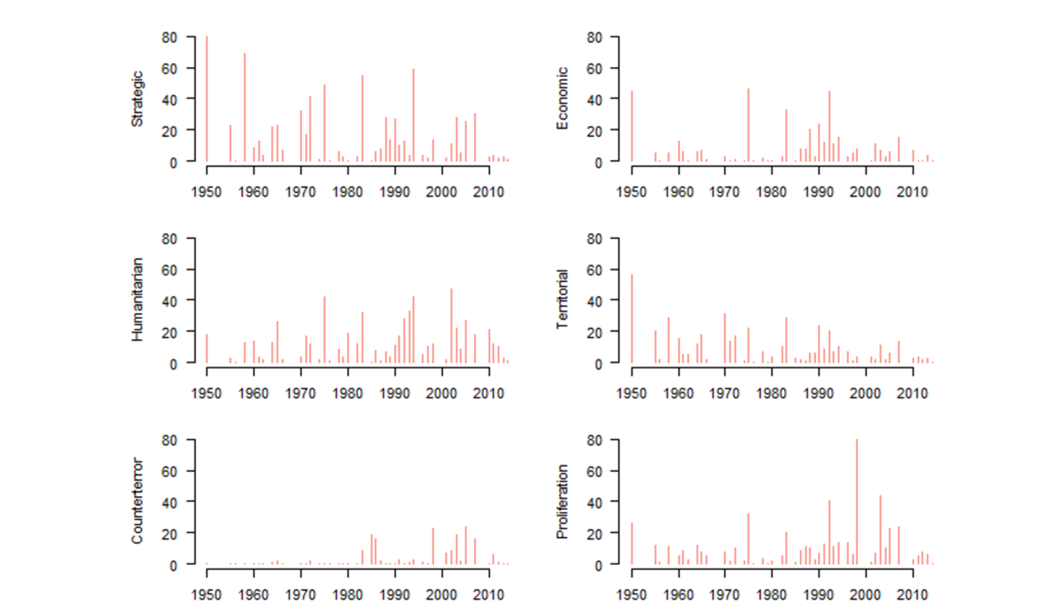

I assembled a corpus of U.S. presidential speeches and remarks that justify the use of force from 1947 to 2014, spanning 62 military interventions. Using a theory-driven dictionary, I then used quantitative text analysis to generate a dataset of how many communication frames related to these motivations featured in each speech.

Next, I merged these with the International Military Intervention dataset, a reputed source that includes variables for the reasons underlying military force, and used statistical analysis to determine if the latter predicts speech frames. Indeed, I find that strategic, humanitarian, and counterterror interventions feature significantly more references to these rationales. For instance, when strategic motivations are present, the number of strategic speech frames is expected to increase by 579%.

Conversely, leaders avoid economic and territorial frames whenever possible. 23% of economically motivated interventions have zero economic frames and 14% have only one. Meanwhile, they are rife with popular communication frames. To illustrate this trend for a territorial conflict, in the 1958 Taiwan Strait dispute, Eisenhower used the highest number of territorial frames (29) in the whole dataset. Yet in that speech, he employed nearly 2.5 times more (69) strategic frames.

This article shows when, why, and how executives aim to lead public opinion, and the evidence begs questions across many research agendas.

Notes

Fig. 1: Justification frames over time

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Air Force Academy, Department of the Air Force, or Department of Defense.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “US Military Intervention and Presidential Communication Frames” by Kerry Chávez.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Author

Kerry Chávez, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Military and Strategic Studies Department at the U.S. Air Force Academy. She is also a nonresident research fellow with the Institute for Global Affairs and an advisor for Project Air and Space Power at the Irregular Warfare Initiative. Previously she was a two-time nonresident research fellow with the Modern War Institute at West Point. Her research focusing on the politics, strategies, and technologies of modern conflict and security has been published in several venues.