On January 20th, 2025, Donald Trump may replace Joe Biden as president of the United States. If this change in party control of the White House occurs, President Trump and his aides will then proceed to fill political appointments with their chosen nominees and get to work reversing Biden administration policies in domains like environmental regulation and immigration. Indeed, common scholarly and journalistic accounts place such ideological conflict at the center of government work. However, in a sprawling executive branch comprised of hundreds of agencies and over 2 million civil servants, much of what these agencies and people do is not particularly ideological. Their work includes weather forecasting at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), cancer research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and keeping official civilian time at the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST).

In a recent article, I develop a novel measure of partisan disagreement about what 93 US federal agencies should do using the perceptions of 1,195 federal civil servants regarding the frequency and intensity of disagreement between Republicans and Democrats in Washington. There is wide variation in the magnitude of partisan disagreement that agencies face. Some agencies must manage high levels of conflict, like those working on environmental and immigration policies, while others operate in relative calm.

In theories of bureaucratic politics, preference divergence between agencies and elected officials, or between elected officials themselves, is a key determinant of outcomes ranging from congressional delegation decisions to presidents’ appointment strategies to civil servants’ career choices. Important scholarship develops measures of agency ideology to characterize this conflict. This scholarship categorizes agencies as liberal, conservative or neither based on expert perceptions of their typical policy views, the self-reported policy views of civil servants who work there, or civil servants’ campaign donations. If political elites anthropomorphize agencies and ascribe to them an ideology or set of policy views, then such measures are clearly important for understanding agencies’ political environments. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency is “liberal” because civil servants working there tend to support efforts to reduce climate change, creating conflict between civil servants and President Trump and his appointees. Similarly, the union that represents US Border Patrol agents endorsed Donald Trump for president in 2016, which is congruent with US Customs and Border Protection being a “conservative” agency. However, if some agencies’ tasks are not ideological, how well does agency ideology measure conflict between elected officials that such agencies face? Moreover, if agencies’ political environments are best understood by focusing on issue politics, how well does agency ideology measure conflict across agencies’ diverse tasks and missions?

Where disagreement is highest and lowest

Figure 1 displays the 15 highest and 15 lowest estimates of partisan disagreement. The agencies at the top of the scale deal with the most contested policy areas in American politics, including environmental regulation (Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], US Fish and Wildlife Service), immigration (US Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS]; US Customs and Border Protection [USCBP]), gun control (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms and Explosives [ATF]), Medicare and Medicaid (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]), food stamps (Food and Nutrition Service [FNS]), and taxation (Internal Revenue Service [IRS]).

The agencies at the bottom of the scale tend to be nonideological or benefit from bipartisan support. These agencies provide nonideological services (Bureau of the Fiscal Service [BFS]) or perform nonideological tasks (National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], National Transportation Safety Board [NTSB], National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST]). These agencies also tend to be scientific agencies that conduct research and provide information (National Science Foundation, NIST, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Agricultural Research Service) or agencies that serve constituencies who have bipartisan support (Veterans’ Employment Training Services, Small Business Administration).

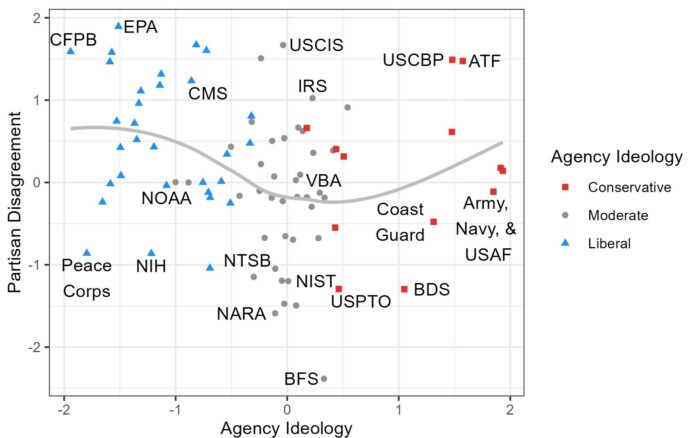

Scholars often use estimates of agency ideology to determine when agencies will be in conflict with presidents and their political appointees, coding liberal agencies as aligned with Democratic presidents and in conflict with Republican presidents, conservative agencies as aligned with Republican presidents and in conflict with Democratic presidents, and moderate agencies as never in conflict. Figure 2 plots the relationship between agency ideology and partisan disagreement, demonstrating that there is considerable heterogeneity in partisan disagreement across the range of agency ideology. The relationship revealed in Figure 2 has three key implications. First, agencies with similar estimates of agency ideology may face different levels of partisan disagreement (e.g, EPA vs. National Institutes of Health [NIH], US Customs and Border Protection [USCBP] vs. Army, Navy, and Air Force [USAF]). Second, agencies with similarly extreme agency ideology estimates may face very different levels of partisan disagreement (e.g., EPA vs. Army, Navy, and Air Force [USAF]). Third, agencies near the center of the scale, which scholars often characterize as moderate and, therefore, never subject to ideological conflict, face both very high and very low levels of partisan conflict (e.g., US Customs and Immigration Services [USCIS] – the agency which oversees the controversial Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program vs. National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST]).

Conclusion

Agencies face vastly different levels of partisan disagreement. If the White House does change partisan hands come January 20th, we can expect large changes in policy agendas at agencies like the EPA, USCIS, and USCBP while agencies like NIH, NIST, or the military service branches are likely to experience much smaller changes (see Figure A.5 in Richardson (2024)). These measures of partisan disagreement improve our ability to characterize agencies’ political environments and understand where the effects of politics on agency operations are likely to be large, moderate, or nearly nonexistent.

Note

Fig. 1: Estimates of partisan disagreement. Horizontal lines are the 95% Bayesian credible interval. Acronyms in parentheses denote the executive department that contain the agency if applicable.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Characterizing Agencies’ Political Environments: Partisan Agreement and Disagreement in the US Executive Branch” by Mark D. Richardson.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse