All around the world, police departments rely on information from citizens to do their jobs efficiently and effectively. While officers spend some of their time patrolling, in busy departments, officers spend most of their shifts responding to calls for service. Even when the police drive on patrol or walk a beat, they don’t do so at random but instead focus on areas that they expect are more likely to require their attention. The information they use to make these determinations comes from various sources, but especially from citizen calls and tips. By relying on citizens to provide information about the community, the police turn the population into a network of eyes and ears, amplifying their ability to monitor the community and allowing them to serve where they are needed most.

In wealthy countries, providing information to the police is trivial for most citizens. In the United States, a person can call 911 from any phone anywhere in the country and be quickly connected to a local emergency dispatcher. However, this type of emergency hotline is far less common and far less reliable in many developing countries. Even where hotlines exist, usage is often low. Experts we spoke with estimated that in most developing countries, only 25%–50% of civilians are aware of an emergency hotline. In the rural Philippines where we conducted our research, much like in thousands of other communities around the globe, citizens wishing to request the police’s assistance must track down an officer, go in person to the local police station, or call the phone number of the specific station in their area where the phone may or may not be answered. Not surprisingly, citizens may hesitate to pay these “search costs” to contact the police, preferring instead to deal with problems through informal means that hamper government legitimacy and reduce public safety.

Recognizing the importance of a centralized hotline, in 2017, the Provincial Police Director in Sorsogon, Philippines, created a province-wide SMS and voice emergency hotline. We worked with the police in Sorsogon to evaluate its effectiveness. Since we did not wish to withhold police services from residents, the hotline was made immediately available to all residents of the province. To determine its impact, we randomized the villages and neighborhoods in which it was advertised. With the help of the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the local governments, we blanketed the randomly-selected “treatment” areas with 55,000 stickers and dozens of large banners that contained the hotline number. Police officers also went door to door explaining the hotline to residents and encouraging them to use it for any issue, small or large.

To make sure that any results were really due to the hotline and not the police’s engagement activities during the advertising, in a second set of areas, the police distributed another 55,000 “placebo” stickers that did not contain the hotline number but were otherwise similar. Officers also went door to door, encouraging residents to contact them with any issues, but did not mention the hotline. Finally, a third set of areas – the control group – did not receive any stickers or police visits.

We surveyed a representative sample of residents province-wide before and after the hotline advertisement to measure its effectiveness. We found that the hotline increased people’s willingness to contact the police, even after accounting for the effects of the police’s door-to-door efforts. Advertising the hotline increased crime reporting by more than 11% among people who had experienced a crime.

This result may seem obvious, but its power lies in the hotline’s simplicity: a single smartphone manned by an officer at the provincial headquarters, who relayed requests to the appropriate municipal station via existing radio channels. The hotline is so simple and inexpensive that it could be introduced nearly anywhere.

Of course, the outcome we really care about is reducing crime. Here, our results were mixed. In the six months of our study, we did not detect any differences in rates of robberies, burglaries, assaults, or drug distribution. The hotline’s only apparent impact on safety was on insurgent activity: residents of areas where we advertised the hotline reported that they were less affected by insurgents compared to residents elsewhere. And concerningly, these same residents reported lower satisfaction with the police than those living in the rest of the province.

What explains this pattern? While we can’t say for sure, the evidence points to a difference between the types of problems citizens reported to the police and the types of problems on which the police focused their efforts. We know from surveying PNP officers that the police view deterring insurgents as a priority. On the other hand, the citizens living in Sorsogon say that ordinary crimes like public intoxication, disputes between neighbors, and assault are the most important threats to public safety that they face. If the police received requests for help on a range of issues but were not responsive to some, it would explain citizens’ decreased satisfaction.

Explicitly encouraging people to contact the police but not responding to the public safety issues they report could harm citizen-police relations. Over time, as citizens fail to see results from the hotline, they may stop using it entirely. Therefore, our study comes with a cautionary note: Cooperation between the police and citizens is a two-way street. The police rely on citizens to provide information, but in return, citizens expect the police to pay back their efforts by dealing with the problems they report. Technological solutions like hotlines can help with one stage of this process but cannot singlehandedly deliver public safety. Only by working together through both stages of this process can citizens and the police achieve their shared goals.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Fire Alarms for Police Patrols: Experimental Evidence on Coproduction of Public Safety” by Matthew Nanes, Nico Ravanilla, Dotan Haim.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

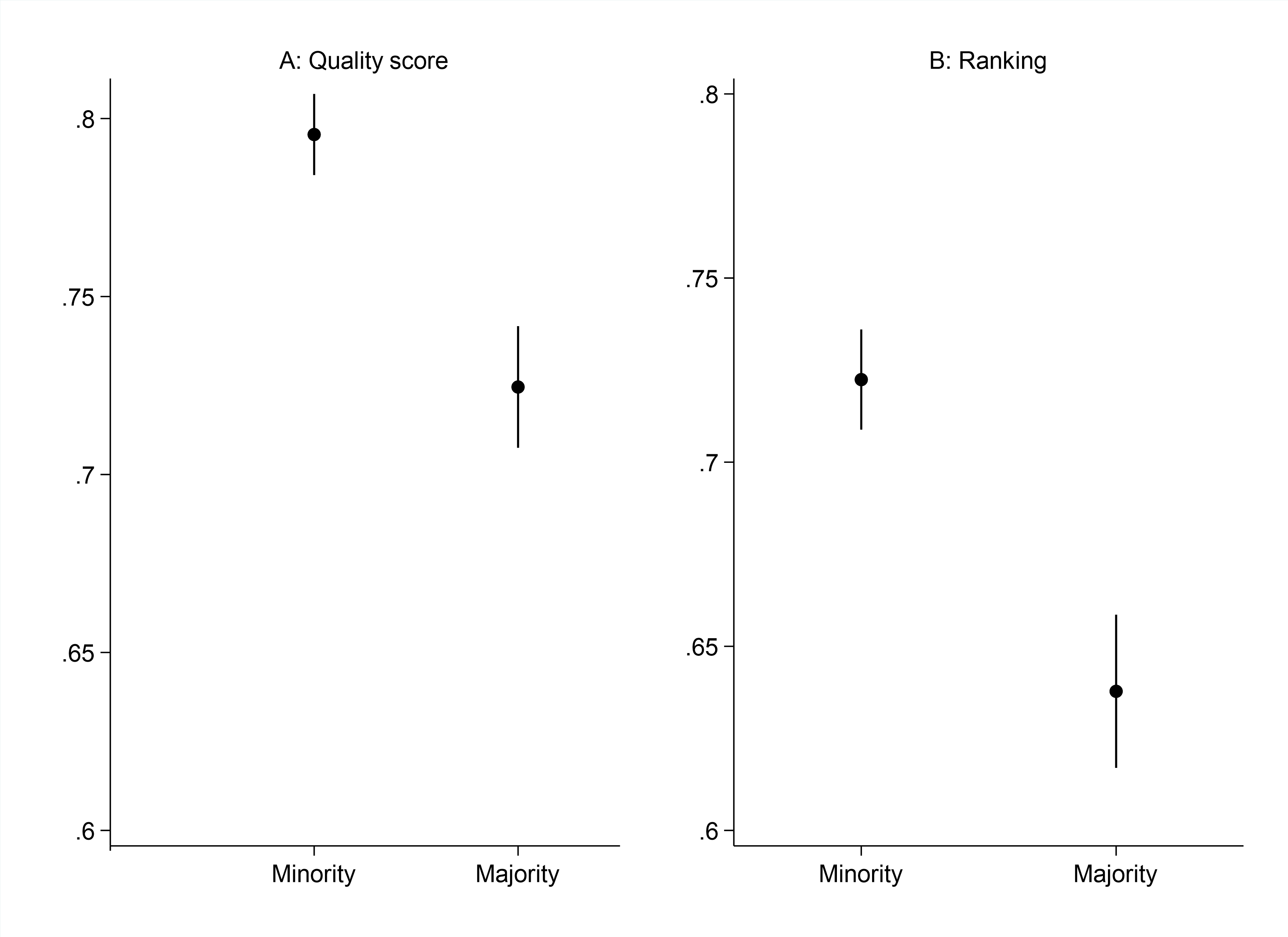

Matthew Nanes. Associate Professor of Political Science, Saint Louis University. Nanes researches domestic security institutions and citizen-state relations, particularly in places plagued by violent intergroup conflict. For example, how does minority integration into the police rank-and-file affect citizens’ willingness to cooperate with police officers? Does marginalization from state security forces motivate anti-state violence? He explores these questions using survey and experimental research in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. For additional information visit his website.

Nico Ravanilla. Associate Professor of Political Science, University of California, San Diego. With his work spanning the political economy of development, governance and policy analysis, Ravanilla focuses on improving governance by improving the quality of the elected government in developing democracies. Methodologically, he designs randomized experiments and searches for natural experiments to answer causal questions relevant to his research. Heavily focusing his research in Southeast Asia, particularly the Philippines, Ravanilla also broadly applies the theoretical insights and policy lessons of his research to other countries in the developing world. More information can be found on his website.

Dotan Haim. Assistant Professor of Political Science, Florida State University. Haim studies conflict, policing, and social networks, with a focus on Southeast Asia. In his work, he uses large-scale social network analysis and randomized field experiments to examine how insurgency and crime can hinge on the nature of the social ties between civilians, government security forces, and local politicians. For more information visit his website.