While not universal, it remains a common refrain that one can’t or shouldn’t evaluate claims of intersectionality with an interaction model. Many of these claims stem from uncertainty about how interaction models work and, indeed, on what even constitutes an interaction model. In our article, we demonstrate that a large class of claims regarding intersectionality, whether quantitative or qualitative in nature, can be evaluated only within an interactive framework. We go on to provide advice on how to interpret interaction models and present results in the context of quantitative intersectionality research. It’s our hope that the theoretical and methodological advice we offer will help to maximize the substantive information obtained from empirical analyses of intersectionality.

While there are different approaches to studying intersectionality, there’s a broad consensus that a fundamental tenet of intersectionality is that it denies the separability of categories of difference such as race, gender, sexuality, class, and disability. While this tenet, which can be considered a necessary condition for a claim to be intersectional, is often taken as given, it is, in fact, a falsifiable claim that can be evaluated in a given setting. An empirical analysis of a particular scenario, for example, might reveal that some outcome of interest is driven solely by gender, solely by race, or separately by both gender and race. Any of these results would falsify a theoretical claim of intersectionality between gender and race in this particular context.

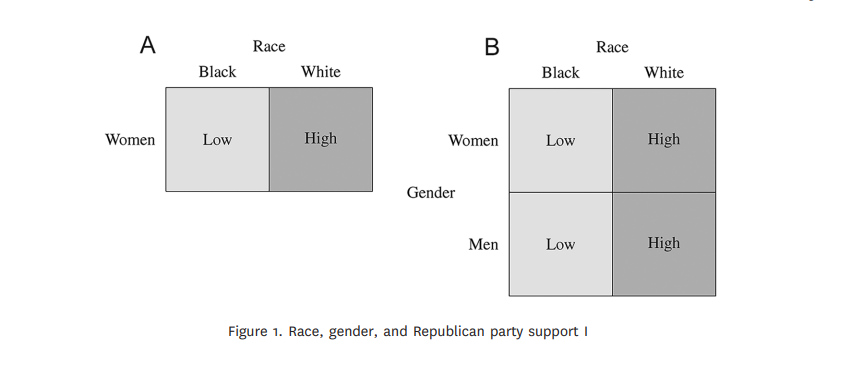

As we demonstrate, claims of intersectionality can only be evaluated within an interactive framework. Evidence of intersectionality can never be directly obtained by studying a single identity group. Nor can it be directly obtained by looking at whether a category of difference, such as race, creates a cleavage within an identity group. This is because heterogeneity within an identity group, such as women, can be consistent with the absence of intersectionality, and homogeneity can be consistent with the presence of intersectionality. Evaluating a claim of intersectionality requires comparing groups that exhibit variation across all the possible combinations of values for the theoretically-relevant categories of difference. This means, for example, comparing four different identity groups when we have two dichotomous categories of difference. Comparing fewer groups than this makes it impossible to determine the necessary quantities of interest to identify evidence of intersectionality. The comparisons required to identify the presence of intersectionality define an explicitly interactive or fully-crossed research design. This is true irrespective of whether scholars use quantitative or qualitative methods to make these comparisons; this isn’t a quantitative-qualitative divide. Among other things, our argument also demonstrates the necessity of including both marginalized and non-marginalized groups in empirical analyses that seek to evaluate a claim of intersectionality.

Many scholars of intersectionality adopt a quantitative approach in their research. Some employ or discuss the use of interaction models. Unfortunately, there’s considerable uncertainty in the literature regarding these types of models, and mistaken beliefs are common. We’ve attempted to correct many of these mistaken beliefs and reduce confusion by providing practical advice on how to specify, interpret, and present the results from interaction models in the context of intersectionality research. As we demonstrate, scholars can adopt either of two equivalent interaction models to evaluate an intersectional theory when the categories of difference are conceptualized as discrete. The ‘standard’ model explicitly specifies the interactions between the categories of difference. In contrast, the ‘alternative’ model includes dichotomous indicators for each of the identity groups created by the categories of difference. While these two models look different, they are, in fact, just different representations of the same model or research design. Their equivalence highlights the fact that comparing outcomes across different identity groups (whether quantitatively or qualitatively) is fundamentally the same as examining how the categories of difference that define the identity groups interact to shape outcomes. We then demonstrate how evidence of intersectionality implies the presence of an interaction effect. Put differently, “no interaction effect, no intersectionality.” Among other things, our methodological discussion illustrates how interaction models are incredibly flexible and can easily deal with complex forms of proposed intersectionality involving multichotomous and possibly unranked categories of difference. It also shows that split-sample strategies, which are commonly employed to evaluate a claim of intersectionality, are implicit interactive research designs.

If we think that applying an intersectional framework is important for understanding the world, then it’s incumbent on us to carefully and systematically think through all the implications of our theories. At a minimum, this means moving beyond a simple claim of intersectionality. Finding evidence of an interaction effect, while necessary, isn’t sufficient to corroborate an intersectional theory. This is because any observed interaction effect is always consistent with a wide variety of ways in which the theoretically-relevant categories of difference intersect, some of which may be inconsistent with our underlying theory. We show, for example, that there are fully fifteen theoretically possible ways that two dichotomous categories of difference can intersect to influence some outcome of interest. In this case, scholars must make what we call “five key predictions” if they wish to determine whether the empirical results they obtain support their particular intersectional story as opposed to one of the other fourteen possible intersectional stories. To date, few existing studies of intersectionality exploit all of the implications of their theory.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Evaluating Claims of Intersectionality” by Ray Block Jr., Matt Golder, and Sona N. Golder.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Ray Block is the Laurence and Lynn Brown-McCourtney Endowed Career Professor in the McCourtney Institute for Democracy and Associate Professor in the Departments of Political Science and African American Studies at the Pennsylvania State University. He is also the inaugural Michael D. Rich Distinguished Chair for Countering Truth Decay at the RAND Corporation. His substantive research focuses on racial, ethnic, and gender group politics, voting behavior, and public opinion in the United States. You can find further information here and follow him on Twitter: @rayblock1.

Matt Golder is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the Pennsylvania State University. His substantive research focuses on political representation, while his methodological research focuses on the use of interaction models to test conditional claims. You can find more information on his website.

Sona Nadenichek Golder is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the Pennsylvania State University and in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen in Norway. Her research focuses on political institutions, especially as they relate to coalition formation and gender representation. She is a former lead editor of the British Journal of Political Science and a current editor for the Oxford University Press book series, Oxford Politics of Institutions. You can find more information on her website and follow her on Twitter: @sonagolder.