Anti-immigrant rhetoric is on the rise in many countries. Often, we assume that this rhetoric is based on racism or ethnocentrism since immigrants arriving to most countries in the Global North often come from different ethnic backgrounds, religions, or races than host populations. Politicians argue that immigrants will fundamentally change the culture and import their divergent beliefs. But, do host communities worry about immigrants’ political beliefs? And what happens if the immigrants share many cultural traits, like race, religion, and language with the communities where they settle?

Why political misperceptions lead to anti-immigrant sentiment

The potential electoral impact of immigrants can be a factor in anti-immigrant sentiment. A third of countries extend the right to vote – particularly in local elections – to resident non-citizens, and many migrants can eventually become citizens and gain full voting rights. Eventual political rights mean the public may worry about how migrants will change electoral outcomes. If locals imagine that migrants hold very different views than they do, they may fear that large-scale immigration will lead to the election of politicians that they don’t support.

How do locals know what political views migrants hold? On the one hand, perhaps migrants eschew the politics of the regime they left. They are voting with their feet, after all. On the other hand, not all migrants leave for political reasons; many have economic or security reasons to migrate. These migrants may approve of the policies of their home government even if they choose to leave or may hold a range of political views. Alternatively, host communities may associate migrants with the countries and politics that they left. Even extreme governments at some point got at least some mass support: Hugo Chavez, for instance, won 56% of the vote in 1998 and continued to draw strong popular support for years.

Politicians and the media in countries that host immigrants have reason to portray migrants as holding extreme political views as well, especially during elections. In the US, Donald Trump played up a conspiracy theory that Democrats have allowed migrants into the US illegally so that they can vote for the Democrats. In Latin America, presidential candidates regularly warn that left-wing politicians will bring “Castro-Chavista” ideas. Such statements can associate opposing parties with extreme views they don’t hold. They also allow politicians to restrict voting access to only their supporters or claim that their loss is due to fraud. Such common portrayals of immigrants as bringing not just their culture–but also their politics–led us to explore the extent of political misperceptions and whether they drive anti-immigrant sentiment.

Voters misperceive migrants’ views: the case of Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia

We test our theory in the context of the mass arrival of Venezuelan migrants to Colombia. Venezuela and Colombia have much in common: they were both Spanish colonies; they were briefly one country; they are Catholic-majority, mixed-race, and Spanish-speaking. However, they have had vastly divergent politics in the last 25 years: until the last election, Colombia had never elected a left-leaning president, while Venezuela has been governed by left-wing populists who have become increasingly authoritarian.

We asked a random sample of 1000 Colombians in two cities, Cali and Cúcuta, Colombia, to assess the political attitudes of Venezuelans in Colombia. At the same time, we surveyed a random sample of 1,600 Venezuelans in those cities about their actual political views.

What we found were stark misperceptions. Colombians vastly overestimate Venezuelans’ support for leftwing politics and their support for the current Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro: 40% of Colombians think that most Venezuelan migrants support the political left and 23% think Venezuelan migrants support Maduro. In fact, these are minority views: only 12% of the Venezuelans support the left and only two Venezuelans (not percent, two people) in our survey support Maduro. Amazingly, Venezuelans were more likely to support the political Right than their Colombian counterparts.

We found similar misperceptions about other political attitudes and behaviors, such as being approached to sell votes and joining armed groups. Locals misperceive migrants’ political attitudes and associate Venezuelans with the leftist regime they fled, even when Venezuelans themselves disavowed their government.

Misperceptions about political views are not just a function of ethnocentrism

One concern we might have is that locals use political concerns — something that is socially acceptable — to hide less socially acceptable views, like racism. To understand if this is the case, we asked our respondents to choose a hypothetical migrant to receive resettlement benefits. Using what is known as a conjoint experiment, we randomly changed the attributes of the two migrants, including their origin (Venezuela or internally displaced in Colombia), their skill level (high, medium, or low), likelihood of employment (cannot work, unlikely to find work, likely to find work), reason for leaving (fear of crime, fear of arrest by the government, poverty, violence by armed groups), race, gender, and importantly, political ideology. Because we as researchers do not know why the participant has chosen any given profile, respondents can express their true views.

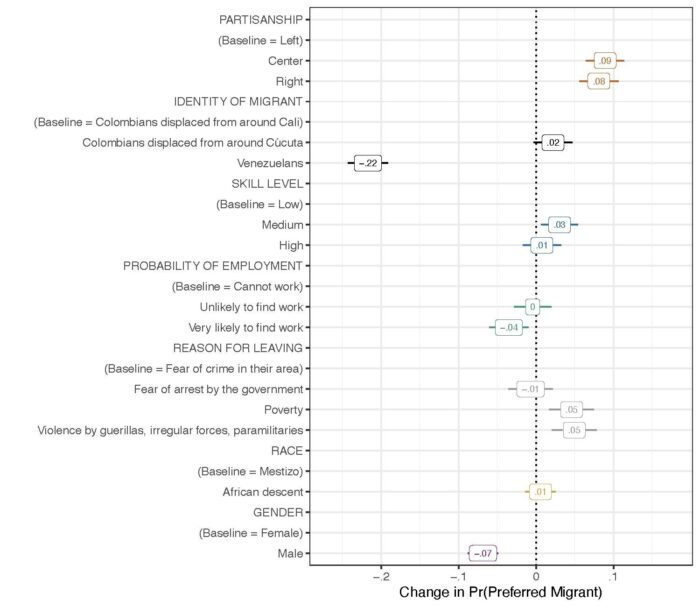

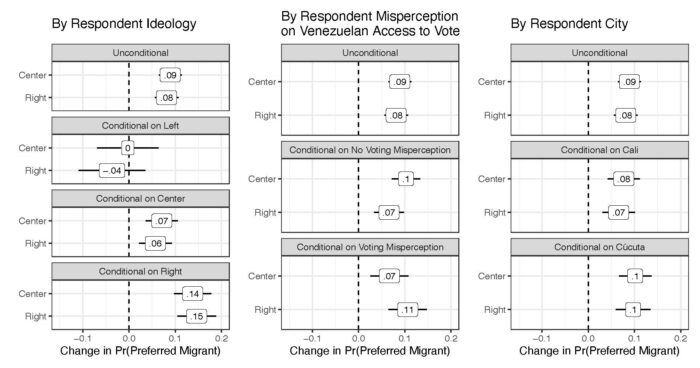

Figure 1 shows how much each attribute matters–or the average marginal component effects. While, perhaps unsurprisingly, Colombians prefer to give resettlement benefits to fellow Colombians, the next most important factor was the political views of the hypothetical migrant. Migrants who are center or right-leaning are much preferred to those who lean left. Figure 2 shows that this preference is stronger among Colombians who are themselves center or right-leaning, potentially suggesting a concern about tipping local election outcomes against their favored party.

Conclusion: Locals should not fear migrants fleeing extreme ideologies

Throughout history, citizens have been concerned about the political ideology of immigrants. Americans were skeptical that a Catholic voter or politician could be independent from the views of the Pope until the 1960s. From the beginning of the Red Scare in the 1920s through the end of the Cold War, those fleeing communism were viewed with suspicion that they might be secret communists.

Yet we find that immigrants fleeing extreme governments more often than not oppose those ideologies — they are genuinely voting with their feet. The political consequences of migration will likely be the opposite of those feared by host countries. In Colombia and the US, as Venezuelans gain the right to vote, they will likely push the electorate further to the Right, not the Left.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Left Out: How Political Ideology Affects Support for Migrants in Colombia” by Alisha Holland, Margaret E. Peters, and Yang-Yang Zhou.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Alisha Holland is a Professor in the Government Department at Harvard University. She studies the comparative political economy of development, with a focus on Latin America.

Margaret E. Peters is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at UCLA and a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Non-Resident Fellow. She studies the political economy of migration and refugees.

Yang-Yang Zhou is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College and a CIFAR Fellow in the Boundaries, Membership, and Belonging Research Program. She studies the political causes and consequences of migration.