Women wait in queues to cast their votes outside a polling station during the 2019 Indian general election. Image: Anuwar Hazarika/NTB.

Inequality in voting turnout across genders implies inequality in political representation. This represents a democratic problem as men and women have different political preferences, and as inequalities in political participation may reproduce other types of inequalities and create a mismatch between policies and actual social preferences. Simply put, when more diverse groups vote, the elected government is more likely to reflect the variety of needs and interests in society.

Employment, in particular for women, is thought to increase turnout and political participation more broadly by increasing incomes; changing power relations in the household; attitudes and identities; increasing access to networks; and make political interests more salient. On the other hand, employment is time-consuming and may therefore reduce participation. In a recent paper, we test how employment affects female political participation in India.

Studying the causal effect of women’s employment on women’s turnout is difficult. We cannot merely compare workers to non-workers as they may differ in a myriad of other ways that is difficult to control for. We identify the relationship by exploiting variation in the availability of jobs in the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS). NREGS is the largest workfare program in the world, employing 40 to 50 million rural households every year. We focus on the largest state in India, Uttar Pradesh, with a population of more than 200 million people, where we have data from over 50,000 polling stations.

The NREGS program provides more than just a salary. It offers women an opportunity to join a community, to build networks, and to engage in conversations about politics. The work is conducted in groups, often bringing together women from diverse backgrounds, castes, and neighborhoods, creating a space for dialogue and connection. This community-building aspect of the program may be crucial in sparking political discussions and improving political knowledge among women, which in turn may lead to higher voter turnout.

We find that the program increases female turnout, and we argue that the effect is caused by increased employment rather than other program-induced changes or omitted variables. While the NREGS work does offer an income, it is typically not substantial enough to be the primary motivator for increased political participation. In fact, the number of days worked in NREGS is capped, and individuals in the program work on average around 30 days per year. We also find larger effects in areas where the program has the largest effects on whether or not women are working, rather than in areas where it is more likely to only increase income. Furthermore, we find no effects on men, who are much more likely to work regardless of NREGS; no effects on party choice, which would be expected if the program increased turnout via pork barrel spending; and no effects on the local concentration of party vote shares, which would be expected if the effect was driven by block voting and mobilization of women voters.

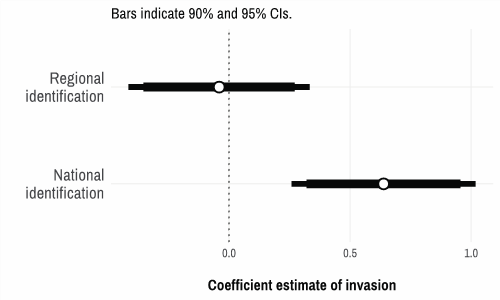

We provide further support for our interpretation of the main result using data collected by Prillaman in the neighboring state of Madhya Pradesh. Standing on Prillman’s shoulders, we show that NREGS employment leads to a larger number of friends in the village, a larger number of people whom women discuss politics with, and to greater political knowledge. Interestingly, we find no effects on bargaining power within the household. We also show that NREGS increases meeting attendance and non-electoral political participation more broadly. In combination with the evidence against block voting, these findings are therefore most consistent with increases in autonomous political participation, rather than elite-induced or mobilized participation. This is important, as autonomous political participation has the potential for furthering women’s agency and making the preferences of the electorate more aligned with those of the population.

Our paper contributes to the small but growing literature on the causal effects of employment on turnout. Previous literature has mostly used trends in the general employment to identify effects and the results are overwhelmingly from developed countries. We specifically contribute by estimating the effects of an actual policy. In the only study with a design to identify causal effects outside of Europe or the US, Aalen et al. (forthcoming in the JOP as well) find that factory employment in autocratic Ethiopia has no effect on turnout intentions but that it lowers participation in community meetings. Aalen et al. argue that their negative finding is due to the extremely poor working conditions in their setting. Our paper contributes to the understanding of scope conditions, in particular considering that we find positive effects of employment in a relatively poor country with low gender equality in general. One possible interpretation is therefore that the work environment has to be minimally hospitable for any positive effect on turnout to materialize. Finally, we are able to study turnout over a relatively long time period, which is important as the effects of employment have previously been found to be temporary.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Female employment and voter turnout – Evidence from India” by Anders Kjelsrud and Andreas Kotsadam.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Anders Kjelsrud is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Oslo Business School, Oslo Metropolitan University. His research focuses on political economy and development economics. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @AndersKjelsrud

Anders Kjelsrud is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Oslo Business School, Oslo Metropolitan University. His research focuses on political economy and development economics. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @AndersKjelsrud

Andreas Kotsadam is a Senior Researcher at the Frisch Centre in Oslo. His main research interests are behavioral economics, development issues, and inequality. You can find further information regarding his research

Andreas Kotsadam is a Senior Researcher at the Frisch Centre in Oslo. His main research interests are behavioral economics, development issues, and inequality. You can find further information regarding his research