Dictators use a variety of tools to maintain their hold on power. Many long-tenured autocrats both retain their office and maintain popular support through sustained economic stability. But autocrats also face bad economic times and, when their ability to provide public goods, buy off elites, or dole out patronage is constrained, they sometimes turn to another tool—repression. Conventional wisdom suggests that in these circumstances, repression (coercive, often violent, sanction by political authorities) is born of desperation and risks triggering popular outrage that can jeopardize the regime. Yet autocrats routinely repress in ways that seem arbitrary or senseless because they appear incommensurate with opposition threats, often indiscriminately targeting civilians. Why, then, do autocrats under economic constraints repress and why don’t civilians mobilize in response?

To answer this question, I study the strategic calculations of autocrats and civilians, and I find that sometimes even indiscriminate repression can have a deterrent effect on opposition mobilization. This is because repression affects civilians’ cost-benefit calculation in deciding whether to engage in antigovernment activity. Repression can make joining the opposition less appealing and incentivize civilians to go about their day-to-day lives, not necessarily as regime supporters but at least not as mobilized opponents.

To show how repression affects civilians’ choice of whether to engage in antigovernment activity, I focus on how civilians vary in their antipathy to the government prior to any repression. Some civilians strongly dislike the government and, importantly, their opposition is identifiable, though they have not yet coordinated with other regime opponents to mobilize a challenge against the autocrat. They may, for example, share criticism of government officials on social media or donate to causes not favored by the government. Because civilians vary in their level of antigovernment sentiment, I distinguish two different types of repression: repression that targets these visible opponents and repression that indiscriminately affects all civilians, regardless of their feelings towards the autocrat. The government can use either or both types of repression to prevent the mobilization of an opposition.

Targeted repression and indiscriminate repression have different effects on civilians. Thus, while the outcome of repression is the same whether it is targeted or indiscriminate—victims may be jailed, disappear, or suffer physical integrity violations—the government has different reasons for employing each. Targeted repression creates a direct security threat for those civilians who are visibly opposed to the autocrat’s rule. When the government increases the level of targeted repression, participating in antigovernment activity carries a greater risk of victimization. This creates a participation incentive that encourages those civilians who oppose the government to opt out of antigovernment activity, instead continuing to live their lives without making a move against the autocrat.

Indiscriminate repression, because it affects regime opponents and supporters alike, does not activate security concerns in the same way as targeted repression. In fact, because civilians are at risk whether they visibly oppose the regime or not, the direct costs of indiscriminate repression do not affect their calculus when deciding to participate in antigovernment activity.

Where my framework departs from most models of repression and opposition mobilization is that I directly trace the implications of the government’s choices for civilians’ material well-being. Specifically, I show how the repression of some civilians can affect the day-to-day lives of other civilians. It is useful to first think about this at an individual scale with a hypothetical example. Imagine an autocrat orders the arbitrary detention of a businessperson. That individual might own land or property that can be seized and redistributed, or government contracts with their business can be given to someone else. In this way, repression can indirectly change material opportunities for those civilians unaffected by indiscriminate repression. My model accounts for this kind of indirect effect on a macro scale. It is important to emphasize that civilians are not necessarily engineering material opportunities from repression, though sometimes civilians do leverage repression to settle scores, obtain government posts, or seek other economic favors. Instead, my model shows how even civilians who are completely uninvolved and may be vehemently opposed to repression can unwittingly see a shift in their material circumstances after the government represses. This creates a material well-being incentive that discourages participation in antigovernment activity.

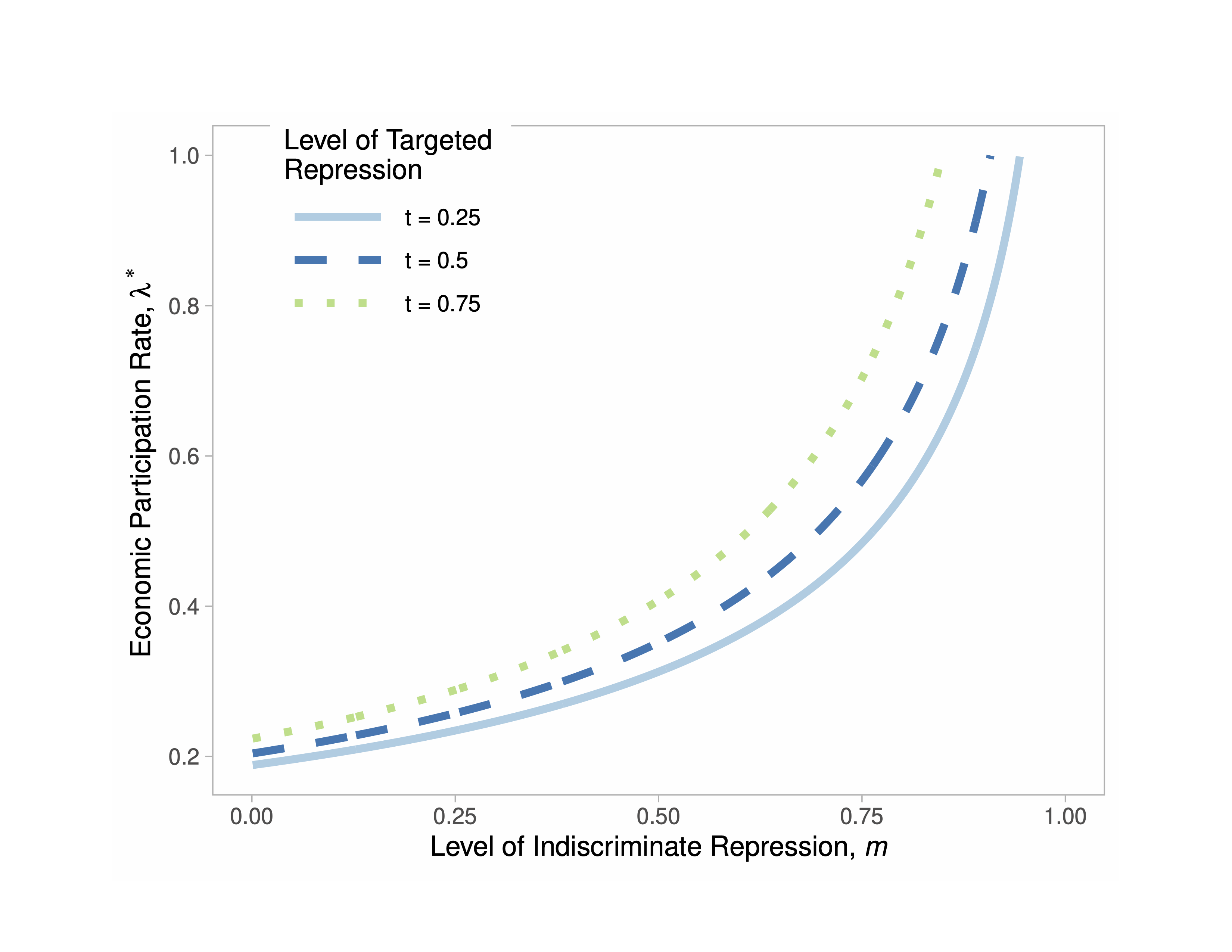

Figure 1 shows that higher levels of repression correspond to more civilians participating in economic activity rather than antigovernment activity. It also shows how targeted and indiscriminate repression are related. As the level of indiscriminate repression increases, economic participation increases and increases faster for higher levels of targeted repression. Because targeted and indiscriminate repression have different effects on civilians’ willingness to mobilize against the autocrat, the government may employ both types of repression concurrently. Moreover, I identify a set of conditions under which the regime gains by increasing targeted and indiscriminate repression together. This means that as the cost of targeted repression decreases—when governments are naturally expected to employ more targeted repression—the regime’s optimal strategy may be to increase indiscriminate repression as well. Complementarity between targeted and indiscriminate repression arises because each prevents opposition mobilization in related ways. First, targeted repression directly reduces the appeal of anti-government activity. Second, indiscriminate repression mitigates economic distortions created by the constrained circumstances under which the government represses. The participation and material well-being mechanisms that drive civilians’ behavior make both types of repression optimal for the government.

I find civilians face the greatest risk of repression from autocrats who face low costs to employing targeted repression, perhaps because they maintain a strong intelligence apparatus capable of identifying potential opponents, and are economically constrained and unable to use other policy tools like patronage to maintain their hold on power. My findings differ from previous work on indiscriminate repression because I focus on a different set of repressive tactics, both lethal and nonlethal, that are difficult to observe, measure, and therefore study. My framework allows me to identify the conditions under which autocrats are most likely to adopt preventive indiscriminate repression to deter opposition mobilization, which is an important precursor to policy interventions that aim to prevent such repression.

Notes

Fig. 1: Effects of targeted and indiscriminate repression on economic participation

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “The Wages of Repression” by Jessica Sun.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Author

Jessica Sun is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Emory University. Her research focuses on civil conflict and political violence, primarily using formal models to explain conflict outcomes and understand how autocrats stay in power. You can find more information about her research here.