Migrants’ Remittances and the Host Country

Billions of dollars cross national borders every day. These financial flows take different forms including currency, corporate investment, and foreign aid. Yet, since 2015, migrants’ remittances have outnumbered them all in low- and middle-income countries. And this trend tells only part of the story. Remittances – that is, migrants’ monetary transfers across national borders – have been on the rise for decades. According to the World Bank, the amount of global remittance flows skyrocketed from $1.93 billion in 1970 to $817.66 billion in 2023. Existing research shows remittances benefit the recipients. They help recipients spend more on healthcare and education, and they provide greater access to public services. Remittances also improve the quality of political governance and contribute to democratic reforms. But less research tells us the causes of remittance flows and whether the country that hosts immigrants plays a role. In particular, do politics in the host country affect remittance flows?

We argue politics in the host country matter. More specifically, we argue politics affect the enforcement of immigration policy that, in turn, affects remittances. The enforcement of immigration policy affects immigrants’ earnings by jeopardizing their residence. If an immigrant expects to be deported in the near future, they have an incentive to save and invest their earnings outside of the host country in case they are deported. In contrast, if an immigrant does not expect to be deported in the near future, they have an incentive to save and invest their earnings in the host country. Think of it as ‘saving for a rainy day.’ Immigrants want funds in case something bad happens. Notice this incentive depends on the intensity of enforcement. Where local officials enforce immigration policy more intensely (by deporting more people), immigrants have a strong incentive to save and invest outside the host country. Where local officials do not enforce immigration policy so intensely, immigrants have a weak incentive to remit money out of the host country. In short, we expect greater enforcement to generate higher remittance flows.

Secure Communities and Remittances to Mexico

We test our thinking in the context of the United States’ Secure Communities Program. The program was federally mandated, and its intent was to more easily identify and deport undocumented immigrants. It marked a shift from its voluntary (and less effective) predecessor, the 287(g) program. Secure Communities exploited a new biometric, file-sharing technology. When potential immigrants were arrested, local law enforcement officers shared their fingerprints with the FBI and Department of Homeland Security. If the fingerprints did not match existing records, then local law enforcement was asked to detain the arrestee for 48 hours until Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) could assume custody. The program made deportations soar. For example, ICE deported 68 immigrants from Tennessee in 2009, that is, the year before Secure Communities was rolled out in the state. Three years later, ICE deported 1,351 immigrants from the state. Variation in deportations across the U.S. provides a great setting for a test of our thinking.

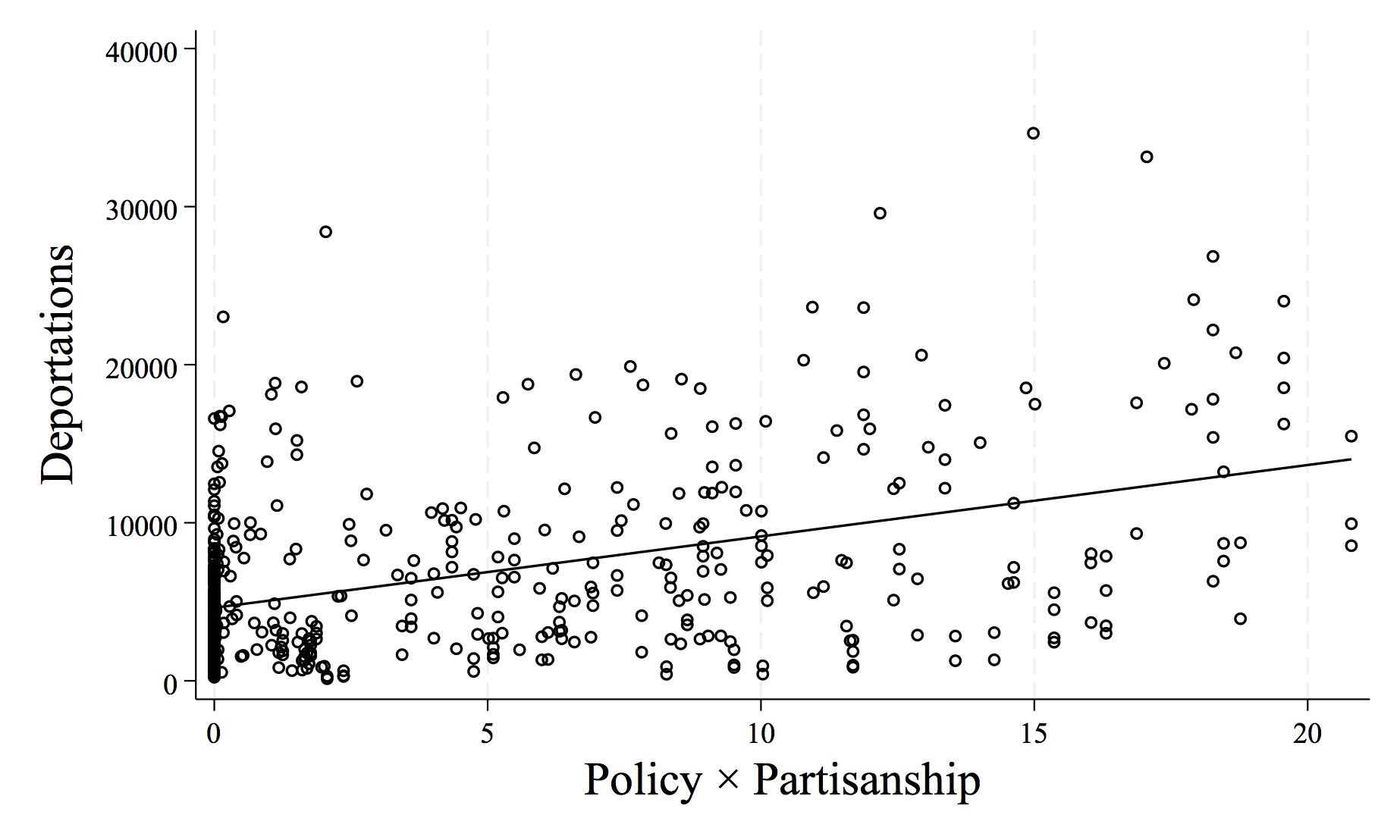

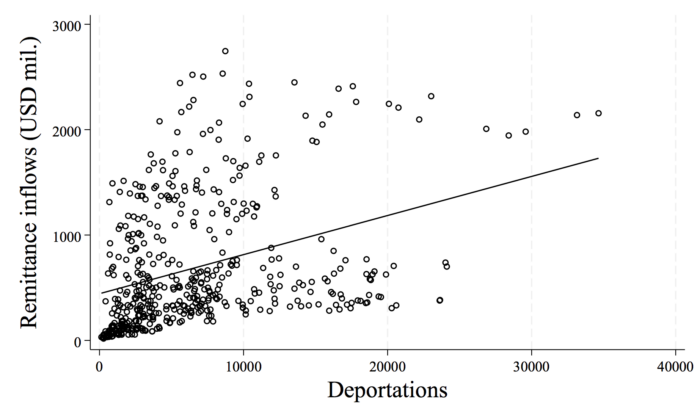

For this test, we use data on Mexican states between 2003 and 2017. We use data on Mexican states since Mexicans form the largest group of immigrants in the U.S. (at the time of study). Also, the Mexican government provides high-quality data on remittance inflows. Our method is a two-stage analysis. In the first stage, we study the relationship between Mexican states’ exposure to Secure Communities, their exposure to Republican support, and their number of deportees from the U.S. Prior studies show Republican areas enforce Secure Communities more intensely than Democratic areas. In the second stage, we study the relationship between the number of deportees to each Mexican state and their amount of remittance inflows.

Deported Money

The results of our analysis support our expectations at both stages (Fig. 1 and 2). First, we find politics in the host country affect the number of deportees to the recipient country. Mexican states with greater exposure to Secure Communities and to Republican voters receive significantly more deportees than other Mexican states. Second, we find the number of deportees to each Mexican state affects its remittance inflows. Mexican states with more deportees under Secure Communities receive significantly more remittances than other Mexican states. In fact, an additional 100 deportees lead to 2.2 million dollars more in remittances, while an additional 6000 deportees (which is not uncommon) leads to 130 million dollars more in remittances. In supplementary analyses, we find this relationship is not due to other factors, such as Mexican states’ exposure to higher wages or employment in the U.S. The supplementary analyses also affirm undocumented, rather than documented, migrants are the contributors to these large remittance inflows.

The results bear a few implications. First, they help fill a gap in existing research. Recall most research focuses on the effects of remittances in the recipient country. Our study turns attention to the causes of remittance flows and the role of the host country. The results demonstrate the importance of politics in the host country to the flow of migrants’ remittances. Second, the results highlight the important distinction between the adoption of policy and its enforcement. Prior studies of Secure Communities focus on its adoption and, thus, assume it is enforced equally everywhere. Yet, local officials enforced the policy differently. Our results highlight that these differences lead to financial differences among the Mexican states. Last, our results imply that intense enforcement creates a financial loss for the host country. Again, we find Mexican states with more deportees under Secure Communities receive significantly more remittances than other Mexican states. A few thousand deportees is equal to hundreds of millions of dollars in lost spending and investment in the U.S. Related research suggests less enforcement, even an amnesty, would reduce flows of money out of the country, which would likely mean continued savings and investment in the host country.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “U.S. Enforcement Politics and Remittance Dynamics in Mexico” by Matthew Smoldt, Valerie Mueller, and Cameron Thies.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Matthew Smoldt is PhD candidate in the School of Politics and Global Studies (SPGS) at Arizona State University (ASU).

Valerie Mueller is Associate Professor in SPGS at ASU and a Research Fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Cameron Thies is Dean of James Madison College and Foundation Professor at Michigan State University.