Contemporary research on political leaders explains their decisions as driven by their desire to remain in power or their personal attributes. Scholarship taking each approach tends to have a blind spot with respect to research in the other tradition, with survival-based theories assuming all leaders will make the same decisions in the same circumstances and arguments focused on leaders’ background experiences, political orientation, and psychological traits frequently ignoring that self-interested incumbents also want to retain office. Drawing on insights from both approaches, I argue leaders’ general willingness to use military force, or hawkishness, conditions the reciprocal relationship between their political prospects and interstate crisis initiation.

The Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies of Hawks and Doves

My argument is built on several well-known results. I focus first on how leaders’ political prospects should influence conflict initiation. First, leaders care about their political survival and differ in their willingness to use force. Second, while the threat of losing power can deter leaders from initiating a crisis, starting a conflict is an attractive choice only for those leaders comfortable using military force. Compared to doves, then, hawks generally should be more likely to initiate a crisis and differences in the probability of initiation should be larger when leaders are politically secure. The intuition here is that the policy autonomy that comes with political security isn’t going to lead a pacifist to start a conflict, but could provide a hawk with enough political cover to do so.

Turning to the other direction of the reciprocal relationship, leaders’ hawkishness should also condition crisis initiation’s influence on their political prospects. First, the role national security considerations play in determining a country’s leadership is increasing in the tension of its relationships with foreign actors. Second, domestic audiences prefer hawkish politicians and policies when facing an external threat. These two observations jointly imply that while leaders’ hawkishness should not influence their chances of survival when conflict is unlikely, hawks’ and doves’ political prospects will diverge and doves will be more likely to lose power than hawks when crisis initiation is likely.

Leader Hawkishness, Political Survival, and Interstate Crises

I estimate how leader hawkishness influences the reciprocal relationship between political survival and crisis initiation between 1919 and 2001 using a structural approach that accounts for endogeneity between the two dependent variables. These analyses reveal several relationships, but I focus on two here.

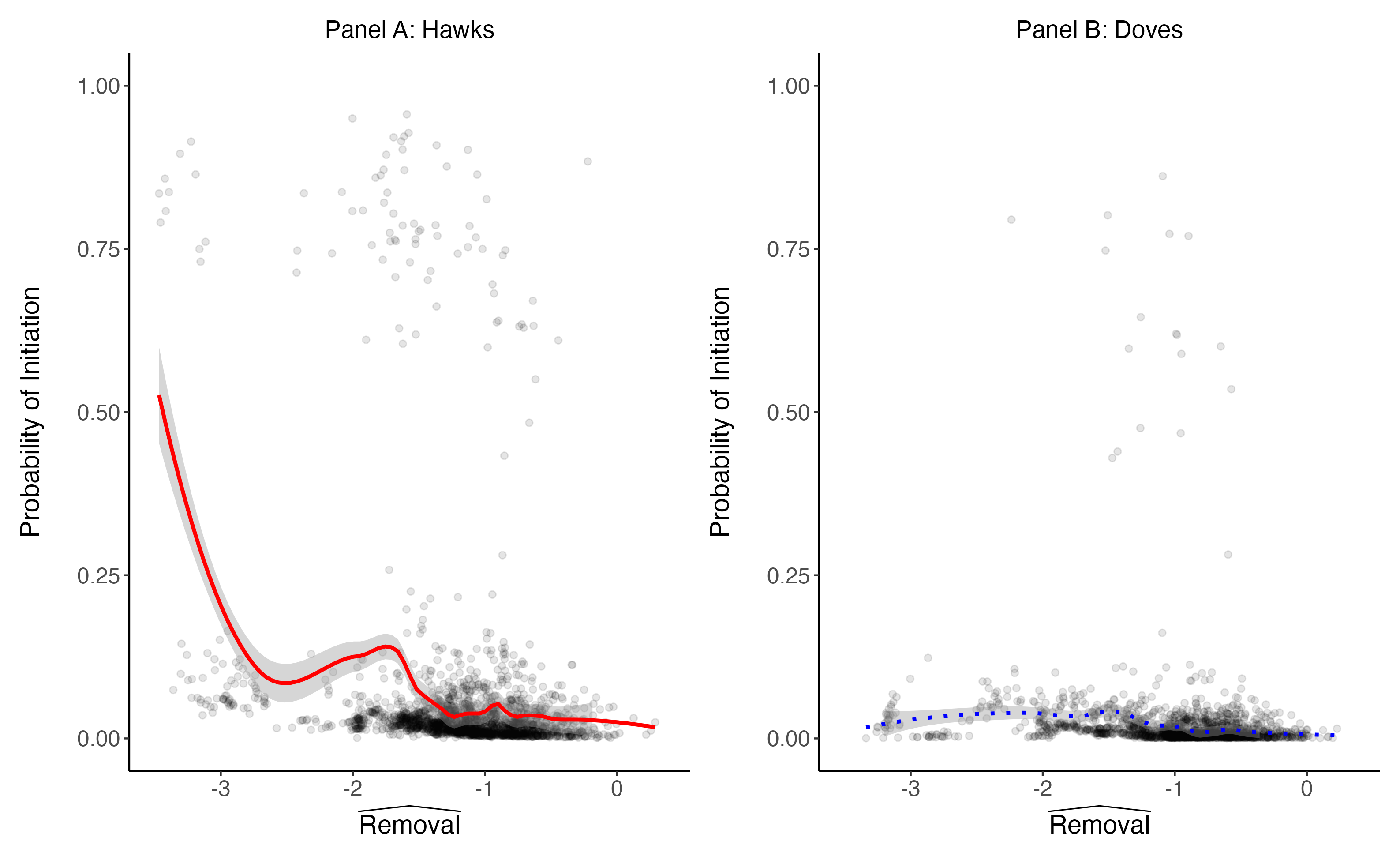

First, the extent to which hawks are more likely to initiate an interstate crisis than doves is decreasing in the likelihood of leader removal (Figure 1). That is, differences in the probability hawks and doves initiate a crisis are more pronounced when leaders are political secure than when they are likely to be removed from power.

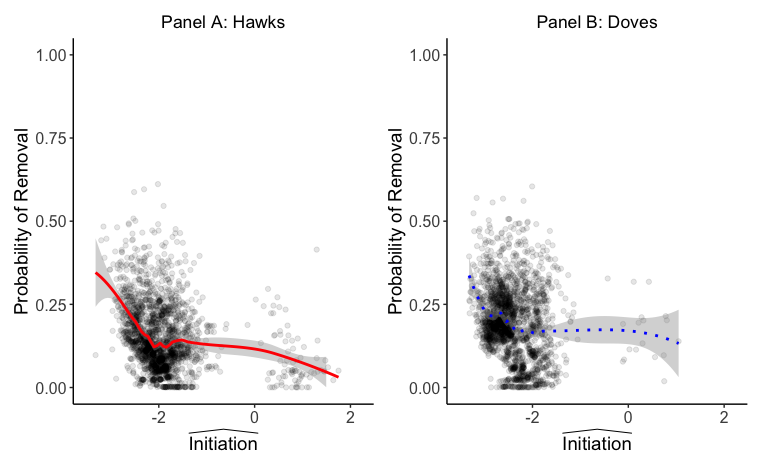

Second, doves are more likely to be removed from power than hawks when structural factors (like military capabilities, having an international rival, or an ongoing territorial dispute) make crisis initiation likely, but not when a crisis is unlikely to occur (Figure 2). This is consistent with foreign policy considerations having a greater influence on who leads a country during times of crisis and war and domestic audiences preferring hawkish politicians when their country faces an external security threat.

Who Comes to Power When a Crisis is Likely?

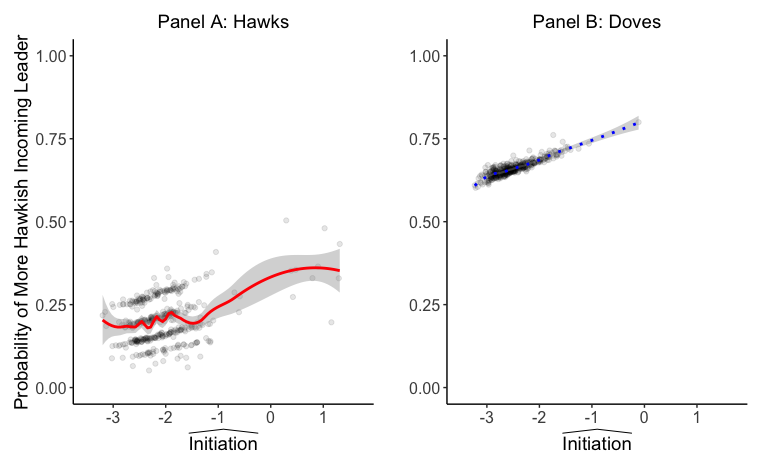

The above findings are noteworthy, but they don’t directly speak to an important question: who are domestic audiences bringing to power when structural factors make crisis initiation likely? The answer determines whether domestic audiences’ preference for hawkish leadership when threatened influences the probability their country will initiate an interstate crisis. I therefore estimated whether incoming leaders are more hawkish than outgoing leaders as a function of how likely crisis initiation is due to structural factors. Increasing the likelihood of crisis initiation is associated with more hawkish leaders coming to power (Figure 3). That is, leadership transitions systematically yield more hawkish leaders when crisis initiation is likely.

Two Implications

My findings have a number of implications for our understanding of foreign policy and international relations. I highlight two here. First, many of our theories likely hold too optimistic a view of how consistently domestic audiences constrain leaders from fighting. Domestic audiences that prefer peace would be well served to remove from power leaders who are predisposed to using force when crisis initiation is likely. Yet, when the chances of initiation are high, hawks are significantly less likely to be removed from office than doves and leader transitions systematically produce new leaders who are more hawkish than their predecessors. The delegation of decision-making authority to leaders who are predisposed to use force when crisis initiation is likely is hard to reconcile with the assumption that domestic audiences consistently sanction leaders who involve them in conflicts.

Second, and more broadly, my analyses demonstrate that analyzing interactions among leaders’ desire to remain in power, their personal attributes, and domestic audiences’ preferences can yield new insights about international relations. The patterns of crisis initiation I find cannot be explained if we assume leaders are driven by their continued political survival or their willingness to use force but can if we consider leaders’ decisions to be a function of both their political prospects and personal attributes. The patterns of leader survival I find are hard to square with the common assumption that domestic audiences punish leaders who initiate interstate conflicts. Accordingly, focusing on how leaders’ political prospects and personal attributes and domestic audiences’ preferences interact can improve our understanding of world politics.

This blog piece is based on a forthcoming article “Leader Hawkishness, Political Survival, and Interstate Crises” by Jeff Carter.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

Notes

Figure 1: The effect of the expectation of leader removal on the probability of crisis initiation for a hawk (A) and a dove (B).

About the Author

Jeff Carter is an Associate Professor at Appalachian State University and the Co-Director of the Correlates of War Project. His research primarily focuses on relationships between political leaders and interstate conflict, how governments pay for war, and state making processes. You can find further information regarding his research here.