When deaths rise or the economy collapses in a crisis, governments in democracies fear for their survival. Everybody knows that unhappy voters can boot them out at the next election. But throwing out the government may not be the end of the story. We examine whether people also blame democracy for bad government performance and turn to authoritarian alternatives. To shed light on this question, we conducted a survey experiment with 22,500 respondents in twelve countries across four continents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

History has provided no shortage of financial crises, natural disasters, wars, or pandemics for governments to manage. In a democracy, one may think that bad crisis management simply leads to government turnover. As a political science folk theory has it, voters in consolidated democracies throw out bad politicians without questioning democracy. However, this account may be too simplistic. Other theories suggest that people see a crisis as a critical test not just for the current government but for democratic politics more broadly. In the COVID-19 pandemic, several commentators and leaders shared this view. For example, US President Joe Biden asserted that democracy must demonstrate to the people that it “still works.” He did not take for granted that when people’s lives and livelihoods are at stake, it’s politics as usual.

Experimental evidence from the worst pandemic in a century

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a useful setting to test whether bad crisis management by the government causes people to change their attitudes about democracy. The crisis entailed a dual challenge, regarding both the health and the economy. We embedded an original survey experiment in a comparative survey on the pandemic fielded in July of 2020.

In the experiment, each survey respondent received comparative information about the health and economic situation in their country. Importantly, the experimental vignettes randomly emphasized different facts and benchmarks. Using this random variation generated from the experiment, we used instrumental variable analysis to leverage differences in people’s satisfaction with the government that were unrelated to their background characteristics and prior political views. This approach enabled us to provide plausibly causal estimates of how much (if at all) dissatisfaction with how the government is handling the crisis also shifted attitudes about democracy.

Democratic dissatisfaction and a silver lining

Analyzing the data from the experiment, we find that comparatively bad performance in the pandemic tends to make people more critical of their government and the way democracy functions in their country. Concretely, we estimate that a one-point decrease in satisfaction with the head of government caused by information about bad performance roughly leads to a half-point decrease in satisfaction with democracy in the country. This suggests a sizeable pass-through from government performance to satisfaction with how democracy works. It’s important to note that this is an average effect in the sample. Not all respondents reacted the same way.

However, in our analysis, increasing dissatisfaction with their government in the crisis typically does not cause people to reject democracy as a principle of government. Nor do they become systematically more enthusiastic about authoritarian alternatives. While blame for bad performance extends beyond the government to the practice of democracy more generally, democracy as an ideal by and large remains unaffected.

The implications of these findings for the health of democracy are ambiguous. It is not the case that when deaths rise or the economy tanks in a pandemic, people automatically blame democracy. Our evidence shows that people use comparative performance information to inform their evaluations of political leaders and democratic practice, though democracy as a principle remains largely uncontested. Beyond the survey we examined, one might hope that the combination of dissatisfaction with democratic practice and commitment to democratic ideals opens the door for democracy-enhancing reforms. Unfortunately, this outcome is far from guaranteed. Another possibility is that political entrepreneurs with an authoritarian streak tap into public dissatisfaction while paying lip serve to democratic ideals.

Note

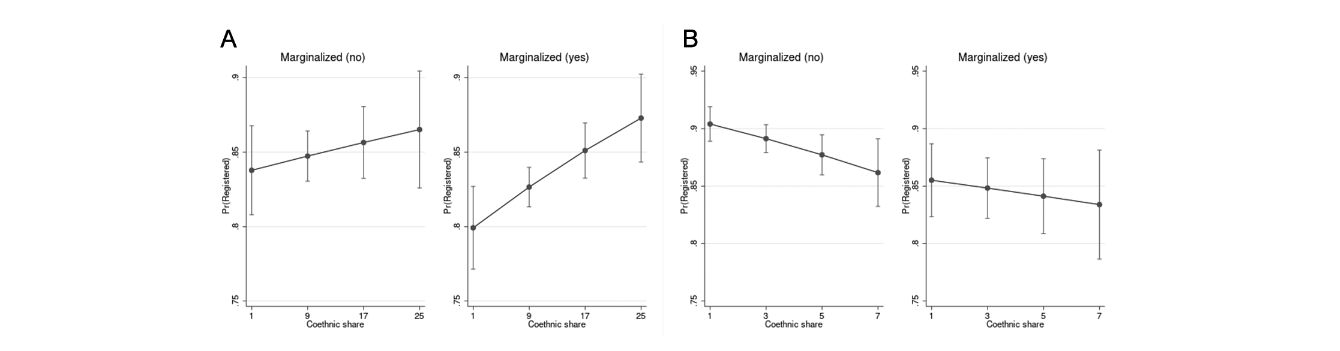

Fig. 1: The figure shows instrumental variable estimates of the impact of satisfaction with the head of government during the pandemic on satisfaction with democracy in their country. The vertical bars are 95% confidence intervals. The analysis includes 22,541 survey respondents. For details, see Table 3 in the article (models 5-6).

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Government Performance and Democracy: Survey Experimental Evidence from 12 Countries during COVID-19” by Michael Becher, Nicolas Longuet-Marx, Vincent Pons, Sylvain Brouard, Martial Foucault, Vincenzo Galasso, Eric Kerrouche, Sandra León Alfonso, and Daniel Stegmueller

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Michael Becher is a professor at IE University. He studies the functioning of democracy with a focus on political institutions, accountability, representation, and inequality. He also studies labor unions in the workplace and beyond. You can find more information about his research here.

Nicolas Longuet-Marx is a PhD candidate at Columbia University. He works on topics in political economy, environmental economics, and empirical industrial organization. You can find more information about his research here.

Vincent Pons is a professor at Harvard. He examines the foundations of democracy: how democratic systems function, and how they can be improved. You can find more information about his research here.

Sylvain Brouard is a senior research at CEVIPOF-Sciences Po. His research focuses on political behavior and on legislative processes in contemporary democracies.

Martial Foucault is a professor at Sciences Po. His research ranges from political economy to political behavior. You can find more information about his research here.

Vincenzo Galasso is a professor of economics at Bocconi University. His research deals with political economics, aging, social security and the welfare state. You can find more information about his research here.

Eric Kerrouche is a senior researcher at CEVIPOF-Sciences Po. His research focuses on decentralisation, parliaments and parliamentary representatives, and public opinion.

Sandra León Alfonso is a professor at Carlos III University. Her research examines issues related to federalism, voting and elections, and distributive politics.

Daniel Stegmueller is Associate Professor at Duke University. His research interests lie at the boundary of political economy, political behavior, and political sociology. You can find more information about his research here.