When the media reports on federal judges, it often refers to the presidents who appointed them. This tendency reflects that many people think that ideology influences judges’ decisions. A wealth of research supports this sentiment. We believe something is missing in this account: the importance of interpersonal relationships among judges in determining the influence of ideology. Faced with enormous caseloads, we expect that appellate judges vary in the deference they give to trial judges based on their knowledge of those colleagues. In the absence of such knowledge, appellate judges are likely to rely on ideological cues.

In our article, “How Interpersonal Contact Affects Appellate Review,” we explore the role of interpersonal relationships, facilitated by contact, on judicial decision-making. Judges generally want to exercise oversight efficiently, especially when they have insufficient resources. When a lower court decision is likely to be correct, there is no reason to expend considerable effort reviewing it. Instead, busy appellate judges rely on cues to determine which cases need scrutiny. When reviewing an appeal, judges can discern whether the lower court ruling is liberal or conservative.

Appellate judges generally prefer to uphold lower court decisions that align with their policy preferences and reverse those that do not. In the absence of other information, the appellate court judge’s ideological alignment with the lower court decision plays a primary role in decision-making. But, lower court judges’ decisions do not necessarily reflect their ideology. For example, they can be motivated to follow existing law by professional socialization, efficiency concerns, or reputation-building. When an appellate judge knows about the trial judge’s skills and biases regarding these other issues, that information may affect the reversal decision.

Geography can help federal appellate judges obtain a higher level of information about some trial court judges. Court of appeals judges review decisions made by district judges in their circuit. Although these appellate judges travel to work with their colleagues, they spend most of their time in home chambers dispersed throughout the circuit. Those chambers are often in courthouses that also office district judges. In 2010, for example, there were an average of five district judges working in courthouses with at least one circuit judge. Judges are more likely to have contact and overlapping social networks when their chambers are in the same city. This geographic proximity allows appellate judges to acquire higher levels of information about the district judges.

When two judges do not know each other well, the appellate judge has less information about the lower court decision’s quality because her ability to develop an independent assessment of the trial judge’s characteristics has been substantially limited. Under these circumstances, the ideological direction of the ruling below plays a comparatively larger role in the decision to reverse. Thus, appellate judges who don’t know the trial judge very well will be less likely to reverse a lower court decision as their ideological alignment with the decision increases.

On the other hand, frequent interpersonal contact can provide an appellate judge with a rich source of information. She may learn that a trial judge is of lower quality than his credentials indicate or that he performs his job with a great deal of care. To the extent that this information suggests that the trial court judge has decided the case correctly, the appellate judge should defer to his decision even when ideological considerations would suggest otherwise. At the same time, when that information indicates that a judge is not skilled, the appellate judge might be more likely to reverse even when the decision appears to align with her ideological leanings. After all, because their decisions are subject to further review, intermediate appellate court judges care about the legal correctness of a decision and its ideological implications.

Working in the same building as the trial court judge enables an appellate judge to access a broader range of information when reviewing that judge’s decisions. In such cases, appellate judges can overcome some of the challenges created when they don’t know much about the lower court judge. Sometimes those considerations will suggest reversal when ideological considerations align; other times, the opposite will be true. On balance, therefore, the introduction of additional information should lessen the effect of ideology on the decision to reverse. Therefore, when two judges interact frequently, the relationship between the appellate judge’s ideological alignment with the lower court decision and reversal should be smaller.

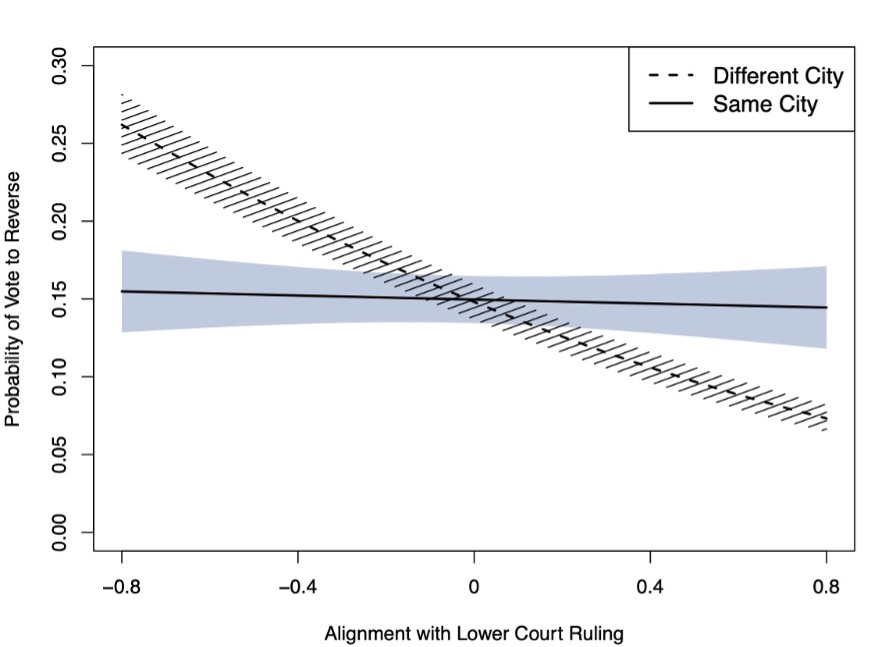

We test our theory with a set of federal search and seizure cases from 1953 to 2010. The results support our theory. Figure 1 illustrates our findings. When circuit judges consider decisions from district court judges with whom they don’t share courthouse space, the influence of ideology is apparent. However, there is no evidence that the role of ideology has any effect when the trial and appellate judges have offices in the same courthouse.

When the appellate and trial judges have offices in different courthouses, the outcome is affected by how much the appellate judge agrees ideologically with the lower court ruling. When the appellate judge and a lower court ruling are both similar (both conservative or liberal), the probability the circuit judge will vote to reverse is less than ten percent. However, when there is a substantial disagreement, the likelihood of voting to reverse can be as high as 25%.

When the appellate judge and lower court judge share the same courthouse, the probability of a reversal vote remains quite constant around 15%. That rate stays the same regardless of the ideological alignment of the trial and appellate court judges.

These findings suggest that interpersonal relationships can condition the importance of ideology on judicial behavior. Contact among appellate and district judges dampens the influence of ideology. Thus, institutional features that influence the extent to which judges have personal relationships with one another, such as circuit size and the presence of in-person networking events, may have heretofore unappreciated consequences for whether a district judge’s decisions stand.

This blog piece is based on the article “How Interpersonal Contact Affects Appellate Review” by Michael J. Nelson, Morgan L. W. Hazelton, and Rachael K. Hinkle, The Journal of Politics, volume 84, number 1, January 2022.

Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the Authors

Morgan L.W. Hazelton is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and School of Law (by courtesy) at Saint Louis University. She earned her J.D. from the University of Texas at Austin and Ph.D. from Washington University in St. Louis. Hazelton studies how features of court systems influence the decisions that both litigants and judges make. You can find further information regarding her research here and follow her on Twitter:@hazeltonphdjd.

Morgan L.W. Hazelton is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and School of Law (by courtesy) at Saint Louis University. She earned her J.D. from the University of Texas at Austin and Ph.D. from Washington University in St. Louis. Hazelton studies how features of court systems influence the decisions that both litigants and judges make. You can find further information regarding her research here and follow her on Twitter:@hazeltonphdjd.

Rachael K. Hinkle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY, and a Research Fellow at the Baldy Center for Law and Social Policy. Hinkle studies judicial politics with particular attention to gleaning insights through the use of computational text analytic techniques. You can find further information regarding Hinkle´s research here.

Rachael K. Hinkle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY, and a Research Fellow at the Baldy Center for Law and Social Policy. Hinkle studies judicial politics with particular attention to gleaning insights through the use of computational text analytic techniques. You can find further information regarding Hinkle´s research here.

Michael J. Nelson is the Jeffrey L. Hyde and Sharon D. Hyde and Political Science Board of Visitors Early Career Professor in Political Science, Associate Professor of Political Science and Social Data Analytics at The Pennsylvania State University, and Affiliate Faculty at Penn State Law. Nelson researches and teaches about courts in the United States and abroad with special attention to public support for courts and judicial elections. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter:@mjnelson7.

Michael J. Nelson is the Jeffrey L. Hyde and Sharon D. Hyde and Political Science Board of Visitors Early Career Professor in Political Science, Associate Professor of Political Science and Social Data Analytics at The Pennsylvania State University, and Affiliate Faculty at Penn State Law. Nelson researches and teaches about courts in the United States and abroad with special attention to public support for courts and judicial elections. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter:@mjnelson7.