Earlier this month, the United States joined more than 40 other countries in announcing the coordination of war crimes investigations in Ukraine. By signing a political declaration in the Hague—the headquarters of the International Criminal Court (ICC)—the Biden administration took its latest step toward recalibrating the US relationship with the ICC. The policy shift was a marked departure from the previous administration. Faced with an impending ICC investigation into alleged US war crimes in Afghanistan, Trump officials attacked the legitimacy of the court and even sanctioned the ICC chief prosecutor. Biden, while opposed to the ICC’s investigation, repealed the asset and travel restrictions and worked toward a relationship reset – policies that may have contributed to the ICC’s decision to “deprioritize” its probe of US actions.

Both Trump and Biden could have ignored the ICC’s investigation of US troops. The United States, after all, is not a party to the Rome Statute, and the Afghanistan investigation was unlikely to lead to a conviction. Yet both administrations felt compelled to respond, albeit in different ways. Why and how do governments defend themselves when they’re accused of violating international law?

Our article “Strategies of Contestation: International Law, Domestic Audiences, and Image Management” examines how governments accused of violating international law can strategically craft responses to mitigate reputational damage. International relations scholars commonly argue that codifying norms through international law intensifies the reputational costs of bad behavior. Yet leaders do not passively accept such costs. Instead, they use strategic rhetoric to minimize negative consequences and shape how citizens view the government. In some cases, leaders may even highlight an international law violation to signal core values to supporters.

Citizens care about many different aspects of a government’s behavior. Some administrations are admired for their foreign policy skills, others for their honesty and integrity. Drawing on organizational theory, we provide a simplified framework for thinking about a government’s overall image. Four qualities may be particularly important to supporters: a government’s perceived moral authority, its performance and general competence, its lawfulness and commitment to legal rules, and its allegiance to citizen interests.

When governments respond to reputational crises, they face tradeoffs between different qualities, and so craft approaches that appeal to the values of their political supporters. A government with many cosmopolitan supporters may want to signal its lawfulness and integrity, while a populist government may be more interested in showing citizens that it looks out for their interests.

What do governments say to defend their behavior? In the context of international law, we argue that image management strategies display varying levels of antagonism toward international rules. Atonement strategies are the least combative, as they do not seek to undermine (and indeed may even reinforce) the value of international law. A government may apologize for its actions or the policies of its predecessors. It may also commit to better behavior in the future.

Disassociation strategies, in contrast, try to distance the government from the bad behavior. The violation may be “accidental” or the result of “a few bad apples.” When the media reported on prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, for example, the Bush administration responded that the actions were “disgraceful conduct by a few American troops who dishonored our country.”

Finally, attack strategies directly challenge international authority. A government may highlight bias in international reporting or complain about the unfairness of international rules. Former President Trump, for example, frequently used attack strategies to criticize the World Trade Organization.

We expect that in practice, strategic leaders will opt for image management techniques that appeal to their domestic political coalition. A leader with supporters who generally favor international law is unlikely to aggressively attack an international rule. For this reason, we test our argument through a survey experiment, which allows us to randomly assign image management strategies following international law violations.

Our experiment begins with background on a relevant international treaty related to torture, trade, or chemical weapons. Respondents assigned to the torture issue area, for example, learn that the US belongs to the Convention Against Torture and that the treaty’s rules prohibit transferring individuals to countries where they are likely to be tortured. We then present a hypothetical scenario where a future US government is accused of a specific violation. An expert body publishes a report about the behavior, generating a debate.

In the experiment, the US government may respond in several different ways. In the control condition, the government says nothing. In the image management conditions, however, the US government responds with a rhetorical defense reflecting the atonement, disassociation, or attack strategies described above.

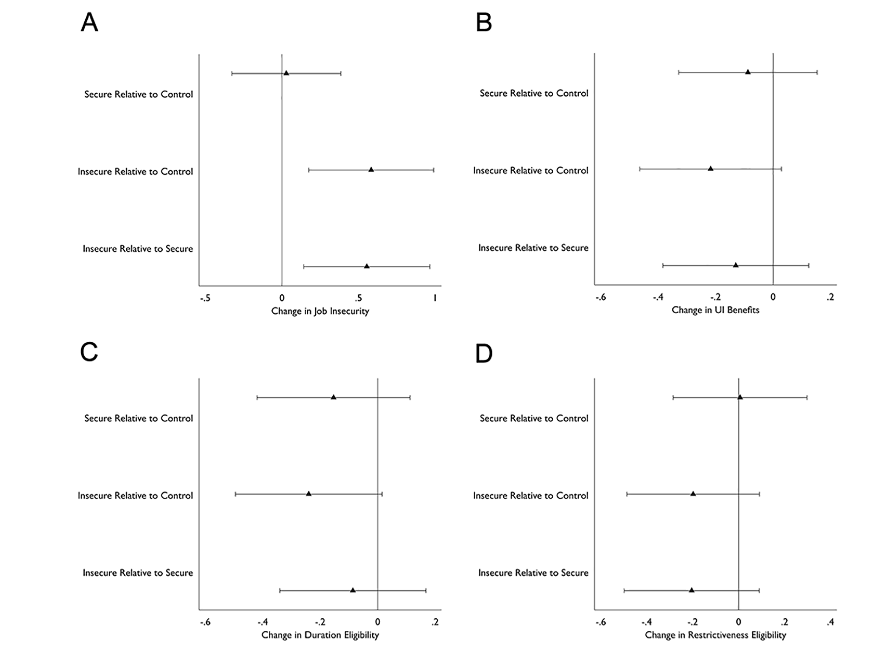

We find that the government’s response affects core dimensions of its image. While all image management mitigate costs compared to the control, atonement is particularly effective at signaling that a government is moral and lawful. In contrast, attack makes respondents view a government as less lawful but significantly more willing to look out for its citizens. Finally, disassociation has positive but muted impacts across all four parts of a government’s image.

Given such tradeoffs, how does a government pick an optimal strategy? It identifies the one most likely to appeal to its supporters. Not all citizens care about the same characteristics. We find that hawks—those that favor a stronger role for the US military in foreign policy—are more likely to support a government that looks out for its citizens. They are also less likely to support governments that signal an interest in abiding by legal commitments.

What does all of this mean for foreign policy? International law violations can become politically salient, even when the issue itself might matter relatively little. Allegations are political opportunities for governments to shape their images with supporters. And as populist sentiment grows, leaders may be increasingly inspired to attack international law for political ends.

This blog piece is based on the article “Strategies of Contestation: International Law, Domestic Audiences, and Image Management” by Julia Morse and Tyler Pratt, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 3.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Julia C. Morse is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on international organizations and global governance, with particular attention to issues of monitoring, compliance, and regime complexity. You can read more about her work here and follow her on Twitter: @JuliaCMorse