American politics offers citizens many opportunities to deliberate together on matters of common concern. Public meetings, local boards, and juries all allow people to voice opinions, hear opposition, and reach decisions with real consequences.

But all of these venues for deliberation suffer from a common problem: they are less racially diverse than the publics they represent. In a time when Americans are increasingly concerned about racial representation in public policy, this raises an important question: would outcomes better reflect the views of racial minorities if these decision-making bodies were more diverse?

With this in mind, we conducted a study to test whether more racially diverse groups make decisions that better reflect the views of racial minority group members. This kind of question can be difficult to study because real-life groups, like juries and public meeting attendees, vary in their levels of diversity for systematic—and sometimes strategic—reasons. For example, attorneys sometimes try to limit the number of people of color on juries in cases where they suspect race will matter. If people of color are kept off these juries precisely when their input could affect the outcome, we won’t see many cases where they are able to do so.

For this reason, we used data from an experiment that randomly assigned people to mock “juries.” Random assignment helps us be confident that more diverse juries are no different from more homogeneous ones.

The experiment brought several thousand Americans together and divided them into six-person groups. These juries were tasked with deciding how much a corporation should be punished for an action (or inaction) that led to an injury. For example, one case involved a secretary exposed by her company to a computer that emitted harmful radiation. Juries in the study made two decisions in two rounds of deliberation: how harshly the company should be punished, on a scale from 0-8, and how much money the company should pay in punitive damages.

Why might a jury’s racial diversity matter in a case of corporate misbehavior? People of color generally—and in our study—prefer harsher punishments for corporations that break laws. This may be because people of color often bear a larger share of the cost for corporate misbehavior like pollution and civil rights violations. We, therefore, expected that groups with more people of color would prefer and reach verdicts that punished corporations more harshly.

Changing Minds

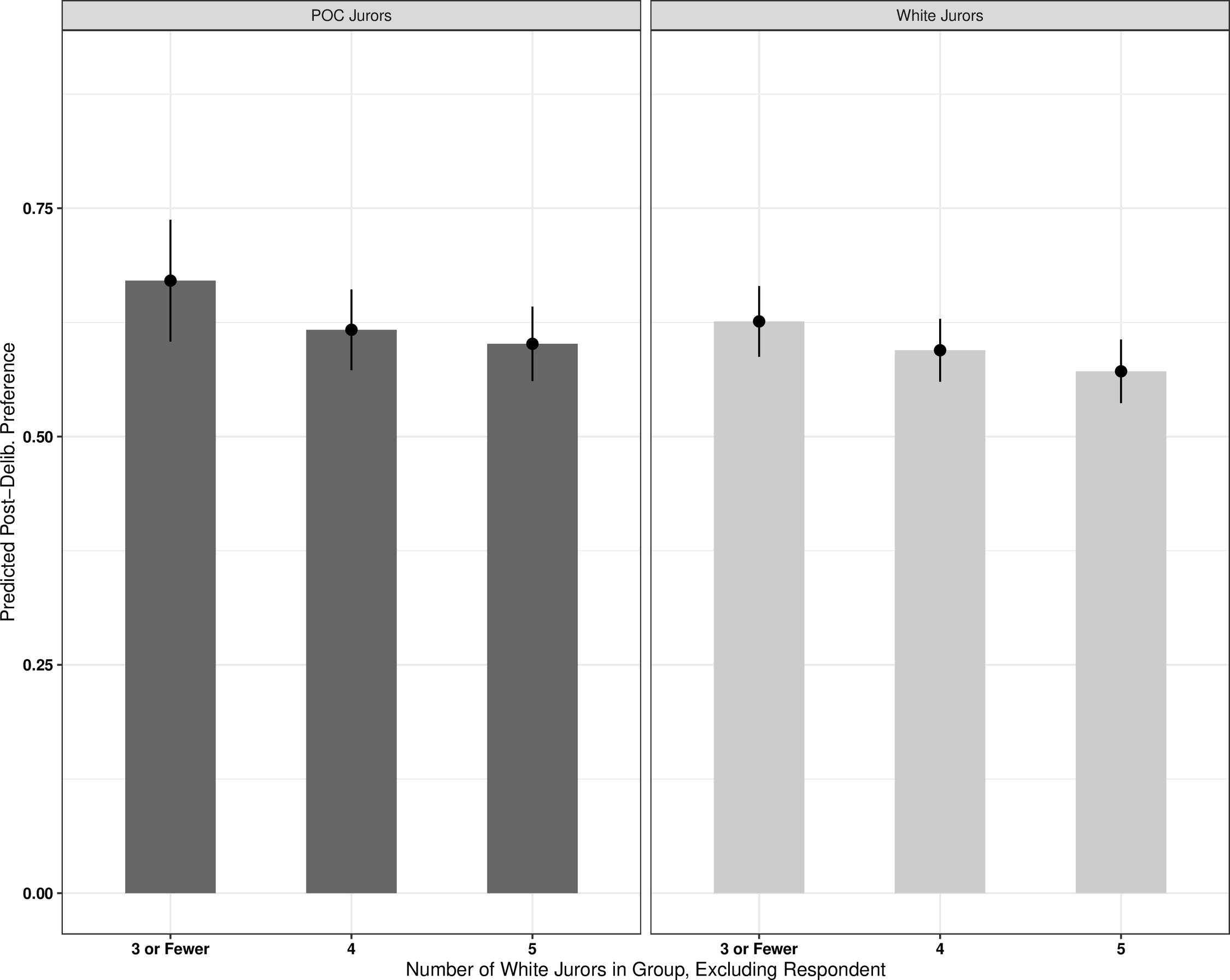

We first asked whether a group’s diversity affected the individual views of jurors. To test this, we looked at preferences jurors privately recorded between their first and second rounds of deliberation. At this point, they had already spent several minutes chatting with their fellow jurors about how the company should be punished, and they were preparing to enter another round of discussion about another outcome. If people of color are influencing their fellow jurors’ opinions, we would expect to see that jurors privately record preferences for harsher punishments at this point.

This is indeed what we find. Both white jurors and jurors of color prefer harsher punishments if they are deliberating alongside more people of color. This is shown in Figure 1 (Figure 2 in the paper): preferred punishments are largest in groups with the most people of color.

Shaping Verdicts

So, deliberating with people of color leads jurors of all racial backgrounds to prefer harsher punishments—punishments closer to the preferences of jurors of color.

But is this movement enough to shape the jury’s decisions? Each jury had to reach a unanimous verdict on how much to punish the corporation, so movement in the opinions of one or a few jurors may not be enough to shape the overall verdict. On the other hand, moving a pivotal voter’s opinion even slightly could be enough to shift the decision.

In fact, we find that juries with more people of color did not choose verdicts that were any harsher (or more lenient) than juries with only white members.

It appears that jurors of color can change some minds on their juries, but this does not translate into changing verdicts. This is not only because people of color tend to be outnumbered on their juries. White jurors with opinions very different from their jury’s are noticeably more successful than jurors of color at bringing their group’s verdict closer to their preferred outcome. In other words, jurors of color whose preferences diverge from those of the other jurors are doubly disadvantaged when trying to affect the verdict: their influence deficit is about 50% larger than the disadvantage white jurors who are similarly different from their jury’s experience.

In ongoing work, we are investigating why this might be. By looking at the transcripts of the mock jury deliberations, we are testing whether white jurors and jurors of color participate differently; that is, whether some jurors speak earlier in the deliberation or raise their preferred verdict more often.

In all, these findings suggest there is some promise to diversifying decision-making groups. In this case, individual minds were changed by the experience of deliberating with more diverse peers. On the other hand, it may be difficult for these changed minds to translate into changed decisions. More work is needed to understand when group decisions are more sensitive to diverse opinions.

This blog piece is based on a forthcoming article “The Effects of Racial Diversity in Citizen Decision-Making Bodies” by Christopher F. Karpowitz,Tali Mendelberg,Elizabeth Mitchell Elder, and David Ribar.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Christopher F. Karpowitz is Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy and Professor of Political Science at Brigham Young University.

Tali Mendelberg is the John Work Garrett Professor of Politics at Princeton University and director of the Program on Inequality at the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice.

Elizabeth Mitchell Elder is a Hoover Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

David Ribar is a consultant at the Boston Consulting Group.