The Covid-19 pandemic crash-tested governments’ ability to protect their citizens in an emergency—a test many spectacularly failed. After fumbling every health policy decision—public facility closures, quarantines, and travel restrictions imposed and lifted seemingly at random—policy-makers got yet another chance to get it right, once the first scarce supplies of Covid-19 vaccines became available. The new question of the day was who to prioritize for the vaccines—an issue of ethics and evidence, the former contested, the latter in short supply.

Two Competing Prioritization Plans

Gun-shy from their previous failures, politicians took the path of least resistance: giving the scarce vaccines to the groups with the highest vulnerability–the most elderly and healthcare workers. Once these two groups were out of the way, however, it became less obvious who was the next most deserving of the life-saving vaccine. The path of least resistance reached a fork: continue with age-based priority or allow groups with high occupational exposure to jump the queue.

We all know what happened: different countries, and sometimes, municipalities within them (for example, US states) took different approaches. Some stuck with strict age-based prioritization, others advanced groups such as teachers, grocery workers, and first responders. Given the dearth of research on the novel virus, these decisions were often made haphazardly and, most importantly, without a clear separation along ideological lines. This was especially the case in the United States, where the Trump administration punted the authority over vaccine prioritization to individual states.

A Natural Experiment

When politicians flail, political scientists are often the ones to benefit. The haphazard vaccine distribution set up a unique natural experiment: some local jurisdictions were assigned to prioritize based on age, while other remarkably similar jurisdictions (but in a neighboring state) were assigned to prioritize based on occupation. For example, Wheeler County in North Central Oregon looks and feels almost identical to Sierra County in Northeast California—both are home to quiet and sparsely populated former mining settlements. But circa March, 2021, a stranded traveler would have but a sure way to find out which of these two counties they were in by stopping at a local CVS pharmacy: Sierra County, CA, was giving vaccine priority to grocery workers, while Wheeler County, OR, was vaccinating individuals of age 65 and older. My job as a researcher was easy, really: all I had to do was collect such twin counties and compare them for trends in Covid-19 cases (and hospitalizations and deaths) before and after California opened vaccine lines to grocery workers (and Oregon did not).

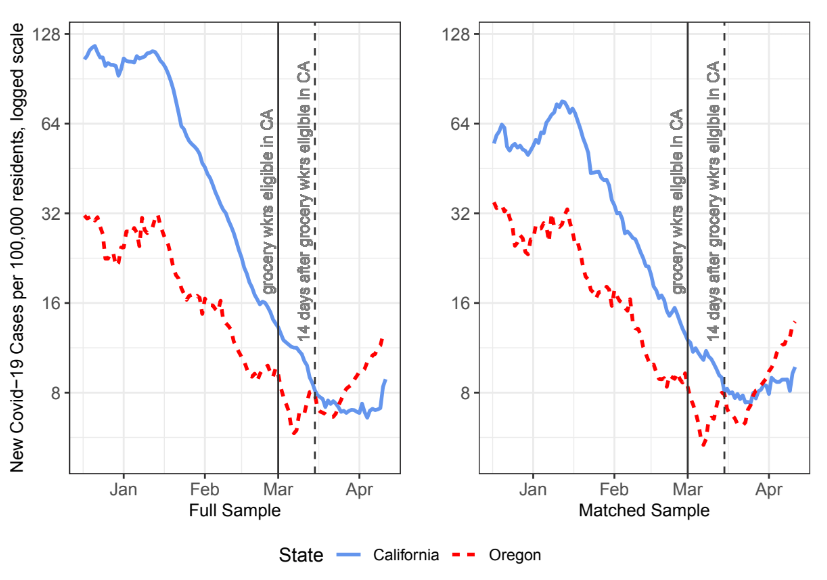

Figure 1 shows the results of this comparison. The daily number of new Covid-19 cases followed a similar trend in the two states between the start of vaccinations in December 2020 and the middle of March, 2021: both experienced a brief period of increasing cases between early to mid-January, 2021, followed by a consistent decline up until early March. In the treatment period—once California expanded vaccine eligibility to grocery store employees on March 1, 2021 (whereas Oregon did not), the two trends diverged. The point of divergence falls somewhere between March 1 and March 15—the latter date is when the grocery employees who had been vaccinated on March 1 would have achieved between 50–80% immunity. After this time, the trend of new Covid-19 cases in California continued to decline, whereas Oregon’s started to increase. At this point Oregon surpassed California in cases per 100,000 residents, its lead peaking in mid-April, 2021 (2 weeks after Oregon also opened vaccine eligibility to grocery workers).

Why Prioritizing Grocery Workers Actually Saves More Lives

These results have a scientific explanation. From the perspective of network theory, contagion—its speed, reach, and main pathways of transmission—depends on the structure of the network. The rate of contagion, in particular, depends on the presence of a few highly connected actors with cross-cutting connections to less connected others. It follows that disabling (or weakening) the transmission potential of the network’s most central actors is the fastest and most effective way to reduce or stop contagion.

As the pandemic raged on, individuals who were most likely to limit their social interactions, as to protect themselves against the virus (for example, due to a pre-existing condition), effectively self-selected into less central network positions. Prior to widespread vaccine availability, most of the general population dramatically reduced their social interactions, with the highest level of social isolation reported by individuals aged 65 and older.

Since essential-service providers, such as grocery delivery people, are the toughest social links to eliminate, giving them vaccine priority is also the most effective way to reduce the risk of infection–for the most vulnerable individuals and everyone else. Conversely, age-based vaccine prioritization is less likely to reduce the spread of the virus, as the key transmitters, such as front-facing grocery employees, tend to skew younger.

Policy Implications

With the Covid-19 pandemic still underway and vaccine access still limited (and uptake low) in many countries, this research provides a theory- and data-informed cost–benefit analysis of giving higher vaccine priority to public-facing essential workers. A key nuance is that, while carrying a disproportionately high potential for spreading the virus, grocery employees make up only a small fraction—less than 1 percent—of the population. To put this into perspective, even given the initial vaccine scarcity, vaccinating every single grocery employee would have delayed vaccine access for other groups by less than a week—a negligible delay given the substantial effect on reducing new case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths, as shown in the analysis.

By fleshing out the trade-offs of different priority sequences, this article opens an informed conversation about the benefits and costs of public health policies as they relate to future disease outbreaks. Beyond public health, this research highlights the value of applying network theory to understand other network-driven social processes, such refugee and migration flows, policy and innovation diffusion, or social media influence.

Notes

Fig. 1: Temporal Trends (State Averages) in Covid-19 Cases, December, 2020–April, 2021

This blog piece is based on a forthcoming article “How to Stop Contagion: Applying Network Science to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution Plans” by Olga Chyzh.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Olga Chyzh is an associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on political methodology, network analysis, political violence, and repressive regimes. You can find further information regarding her research here and follow her on Twitter: @olga_chyzh.