With US federal funds rates hovering over 5%, many mourn the passing of an era of cheap credit in the global economy. High as they might seem, however, interest rates on mortgages and consumer credit have been low by historic standards over the past 25 years, leading to the idea that individuals can access credit to face temporary unemployment or disability instead of drawing from public insurance schemes funded by the taxpayer. Scholars refer to this system as a “credit-based social policy”.1,2 (Mertens 2017). A credit-based social policy seems attractive because it reduces public outlays that put immense pressure on taxpayer-financed spending. Furthermore, a credit-based social policy allows individuals maximum freedom in choosing protection commensurate with their level of risk aversion. On the flip side, a credit-based social policy “individualizes” economic risks that citizens might prefer to “socialize”. After all, some individuals may be frozen out of the credit market and therefore unable to protect themselves in case of bad luck.

Credit vs insurance?

Independently of the availability of cheap credit, many individuals already take advantage of the existence of private insurance against economic downturns — poor health, in particular — to complement publicly-available insurance schemes. Arguably, some of these individuals would prefer to entirely opt out of social insurance schemes if this were a possibility. Even when it is not, the availability of private alternatives softens the degree of popular support for social insurance.3 At this point, some risks — for example, the risk of unemployment — are not yet fully insurable. In other words, countries lack well-developed markets where financial institutions compete to offer policies against income loss. We contend that enhanced availability of bank loans can serve as a substitute for insurance against risks not yet covered by the market. Yet, we also submit that not everybody will be willing and able to forgo social insurance. In fact, we conjecture that only individuals working in sectors with low unemployment risk and those with high incomes would ever entertain the notion of substituting access to credit for social insurance.

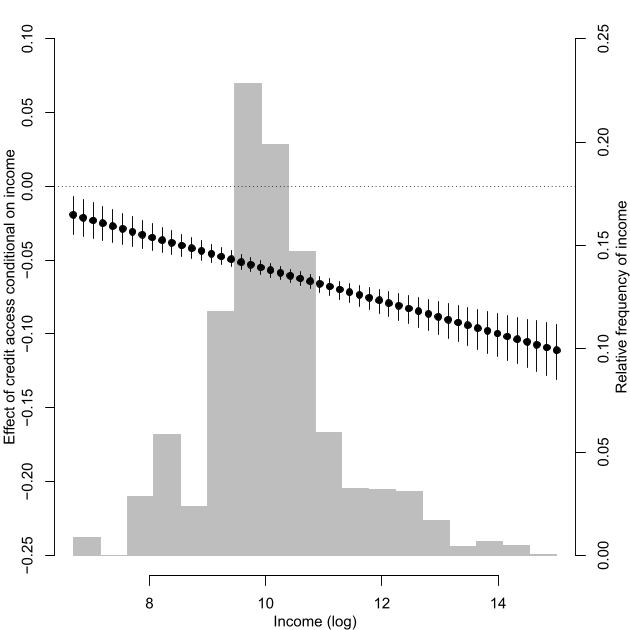

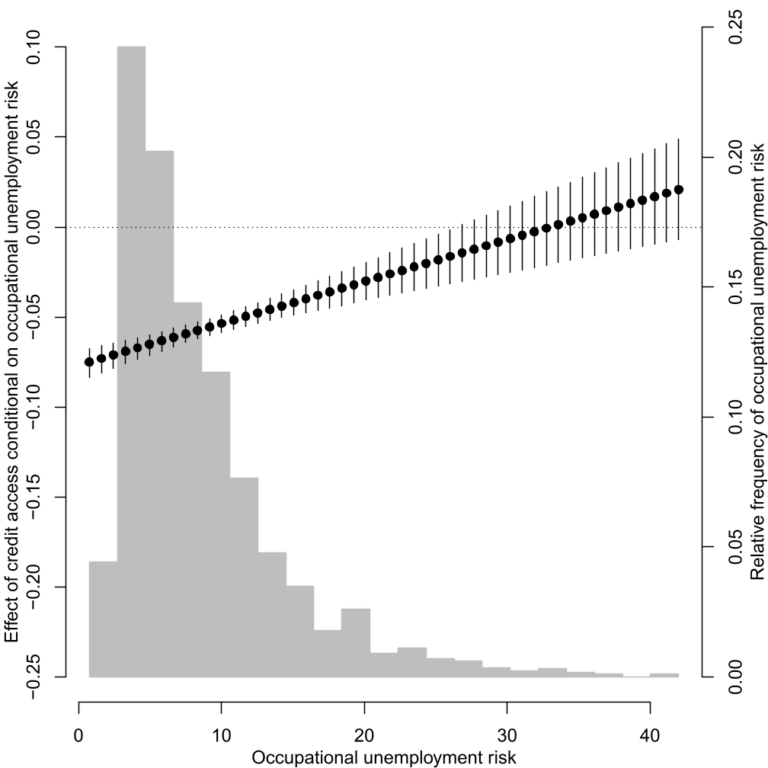

To test this conjecture, we turn to the general-purpose European Social Survey (ESS), which gathers attitudinal data from nationally-representative citizen samples in 31 participating countries. We inspect five biennial ESS waves from 2002 to 2010 in 23 countries for which relevant data are available. These surveys contain respondents’ attitudes toward general redistribution (to what extent do you agree with the following statement: “The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels”) along with self-reports on the difficulty that a respondent would face if they were in financial difficulties and needed to borrow money to make ends meet, which we suggest is a reliable measure of an individual’s access to credit. We find, consistent with our conjectures, that access to credit reduces a respondent’s agreement with statements about general redistribution (Figure 1). Similarly, we obtain evidence that access to credit lowers support for redistribution among respondents in occupations with relatively low unemployment risk (Figure 2).

The survey evidence we uncover is hardly dispositive, as it depends on self-reports about access to credit and replies to a very general question regarding the desirability of government redistribution. To circumvent these problems, we designed a survey experiment where we asked a balanced sample of 1286 respondents in the United Kingdom to compare six pairs of hypothetical societies that varied in the generosity of their social safety nets, the fiscal burden on the taxpayer and, crucially, the interest rates charged on credit cards and mortgage loans. Along with their opinions, we also requested information on respondents’ household income and occupations. The United Kingdom is an ideal scenario to field this particular experiment because reforms that have cut into the country’s social safety nets coupled with fast credit expansion approximate conditions implied by the notion of credit-based social policy, but also because the 2008 economic crisis generated high rates of household indebtedness that lay bare the potential negative impacts of credit-based social policy. In short, we expect respondents to be clear-eyed about the costs and benefits of thinking about credit as a substitute for welfare.

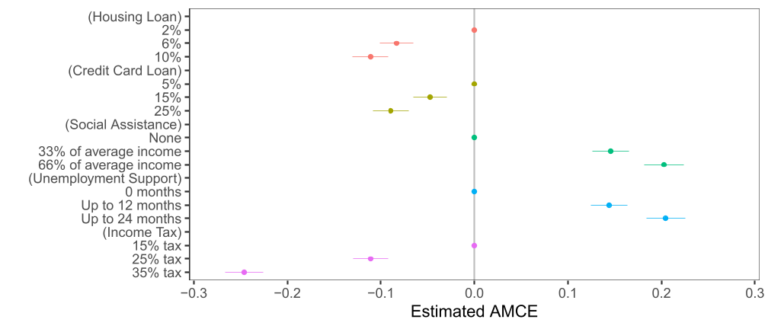

We see evidence that our experiment is successful in eliciting attitudes about the different characteristics of the fictitious societies that respondents confront. Unsurprisingly, respondents become less likely to choose societies as their tax burden and interest rates increase; predictably, respondents are more likely to choose societies with more generous social assistance and unemployment support (Figure 3). When we break respondents down according to their income (affluent vs low income), we find evidence of a credit—insurance trade-off only among the group of affluent respondents. In particular, we find that high-income respondents are disproportionately prone to dislike scenarios with high fiscal burdens when credit card loans and mortgage loans are available at cheaper rates. Similarly, a breakdown of respondents according to the risk of unemployment in their current occupations (high vs low risk of unemployment) suggests that only low-risk individuals are disproportionately prone to dislike high fiscal burdens when cheap credit is available.

What we learned?

We know from previous work that decisive coalitions of voters, including affluent ones, have stopped big cuts to welfare programs. In the context of expanding credit-based social policy, those that can use loans instead of welfare, might stop supporting the continuation of social safety nets, especially in the area of social insurance against economic risk. Our research provides some evidence that mainly wealthy voters and those who are not worried about losing their jobs might prefer cheap access to credit instead of government help. Low-income high unemployment risk voters, in contrast, do not find loans, even at potentially low rates, a good replacement for social insurance. Thus, instead of fixing economic and social problems, increasing the availability of loans could make disagreements about the extent of welfare worse by increasing the divide between those who pay into the system and those who get benefits from it. We might end up welcoming, rather than ruing, the advent of slightly more expensive money implied by high fed fund rates.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Borrowing to Self-Insure? Credit Access and Support for Welfare?” by Jonas Markgraf and Guillermo Rosas.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Jonas Markgraf is an Economist at Amazon. He previously was a Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford, Nuffield College, and holds a PhD from the Hertie School Berlin. His academic research focuses on the connection between politics and the financial sector.

Guillermo Rosas is a Professor of Political Science at Washington University in St Louis. His research focuses on the economic consequences of political regimes and on the effects of political institutions on political elite behaviour, He is the author of Curbing Bailouts: Bank Crises and Democratic Accountability in Comparative Perspective (University of Michigan Press, 2009) and co-author of Latin American Party Systems (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and The Chain of Representation: Preferences, Institutions, and Policy in Latin America’s Presidential Systems (Cambridge University Press, 2021).