Sometimes technological backwardness is a blessing. A backward country doesn’t need homegrown science to invent a new technology or domestic industry to produce it. A backward country can simply buy technology from developed countries. As Veblen (1915) and Gerschenkron (1962) taught us, this constitutes “an advantage of backwardness”.

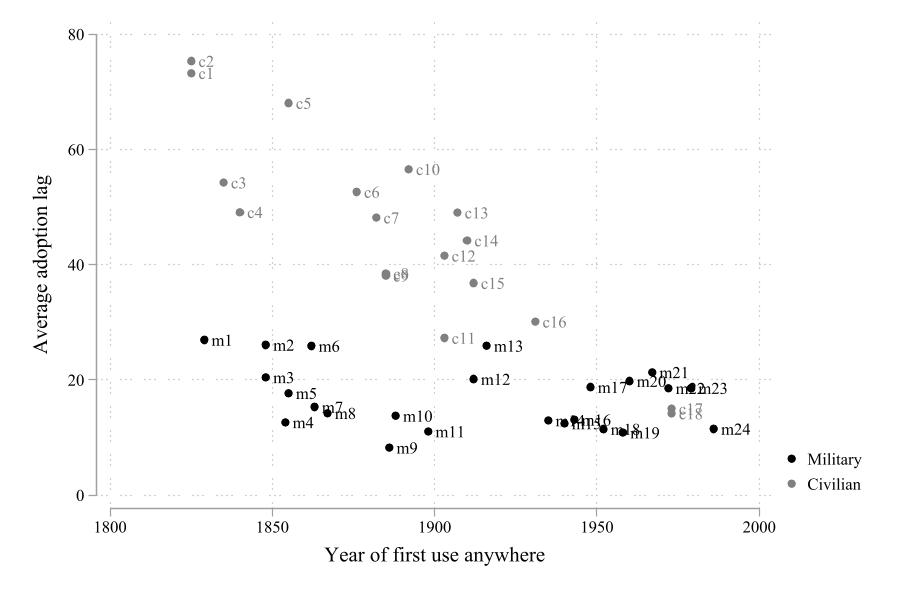

But technologies differ, and developing countries do not adopt all types of new technology at the same speed. One fundamental distinction is between arms technology and productive technology: Since at least 1850, non-Western countries have generally adopted new arms technologies much faster than other forms of new technology. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

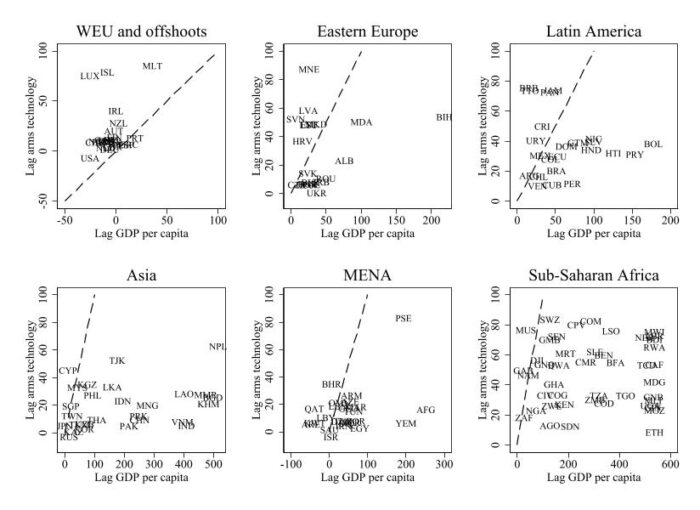

The uneven pace of technology adoption meant that rulers in developing countries often acquired sophisticated arms technology when the rest of the country was still at an early stage of socio-economic development. This contrasts sharply with the experience in Western Europe where societal modernization and technological development (whether arms or not) went hand in hand. We refer to this general phenomenon in developing countries – the adoption of sophisticated arms without concomitant modernization – as a “coercive imbalance”. To illustrate the magnitude and distribution of “coercive imbalances”, Figure 2 shows how much countries in six regions lag behind the technology frontier in both economic development and arms technology.

The dashed 45°-line represents “balance”, an identical lag in both dimensions. Countries to the right of the dashed line have a coercive imbalance – they are more advanced in arms technology than in development. In all regions, except Western Europe, the majority of countries lie far to the right of the 45°-line.

We argue that coercive imbalances outside Western Europe created fundamentally different structural conditions for political development than in the West. The coercive imbalance meant, for example, that rulers outside of Western Europe could entrench themselves with modern arms at a time when societies were weakly modernized and the demand for political reform still limited. More broadly, modern arms technology tends to strengthen the state as against society, meaning that the power balance between rulers and societal actors outside of Western Europe was fundamentally different from that in Western Europe. This helps to explain the divergent institutional trajectories between the West and the Rest.

We base these conclusions on empirical evidence from a new data set on arms technology adoption across all countries since 1850. We document the existence of the coercive imbalance outside Western Europe and show that it was caused by an uneven speed of technological adoption. We go on to document that the coercive imbalance leads to lower levels of democracy, more repression, and corrupt bureaucracies. To show that the effect is causal, we use an instrumental variable strategy based on geographical diffusion patterns combined with the timing of innovations in arms technology.

The discovery of the coercive imbalance and the consequences of it contribute to our understanding of one of the foundational questions in the social sciences: “Why Europe?” Why did participatory government and bureaucratic administration arise in Europe and not elsewhere?

The literature is in broad agreement that what was distinctive about Europe was the balance of power between rulers and societal actors. Many historical factors have been proposed to explain the distinctive European balance including feudalism, the Catholic Church, or autonomous towns. To this set of factors, we add the coercive imbalance: In Europe arms developed as part of a process of modernization, which also empowered societal actors; outside of Europe, the swift adoption of arms tilted the power balance in favor of rulers before societies modernized. It is worth noting that this is not only an historical phenomenon: it still exists today. The discovery of the coercive imbalance, thus, allows us to explain the divergent paths of Western Europe and the rest of the world without relying on centuries of path dependence.

It suggests that, today, democracy may not follow as naturally from modernization as it did in Western Europe. Even if economic development still generates a demand for political reform, the swift adoption of advanced arms technology has allowed rulers to entrench themselves. Now, therefore, the Western European experience, as summarized in modernization theory, will not generalize outside of the continent.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Arms Technology and the Coercive Imbalance Outside Western Europe” by Jacob Gerner Hariri and Asger Mose Wingender.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Jacob Gerner Hariri is a professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. He works on comparative politics and historical political economy, with an emphasis on state formation and the origins of democracy.

Asger Mose Wingender is an associate professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Copenhagen. He is interested in economic growth and development, particularly in the role agriculture plays in this context. He also moonlights as a political scientist studying the economic origins of democracy.