Eras of American politics are often characterized as being either “party-centered” or “candidate-centered.” While observers today lament the modern combination of polarization with relatively weak parties, in the past scholars have decried both candidate-centered politics (APSA Committee on Political Parties 1950) and politics centered around strong parties. The latter was the target of Progressive reformers around the turn of the 20th century, who questioned the influence of parties and championed party-weakening reforms. These reforms, including the secret ballot, the direct primary election, and non-partisan elections, achieved widespread use over a relatively short period of time, and profoundly shaped American politics (e.g. Hirano and Snyder 2019). But did they usher in an era of candidate-centered politics?

The conventional wisdom is that during the late 19th century US electoral politics mainly revolved around parties, but by the early 1970s the electoral environment had largely shifted to focus on the candidates and their campaigns. The timing of this shift – and therefore its causes – is somewhat less agreed upon. Some argue that it occurred sometime in the 1950s or 1960s, but more recent work argues that the transition began several decades earlier. Our project addresses this important puzzle by asking whether Progressive Era reforms like the secret ballot, direct primary elections, and non-partisan elections generated a change in the “candidate-centeredness” of campaigns. To answer this question, we made a new dataset of political advertisements that appeared in newspapers during the week prior to an election. Our dataset includes 90 newspapers, and overall spans the period 1880 to 1930. While newspaper advertising is not the only way to measure candidate-centered campaigning, it does capture the effort that candidates put into elections, in a medium that was hugely important during our period of study.

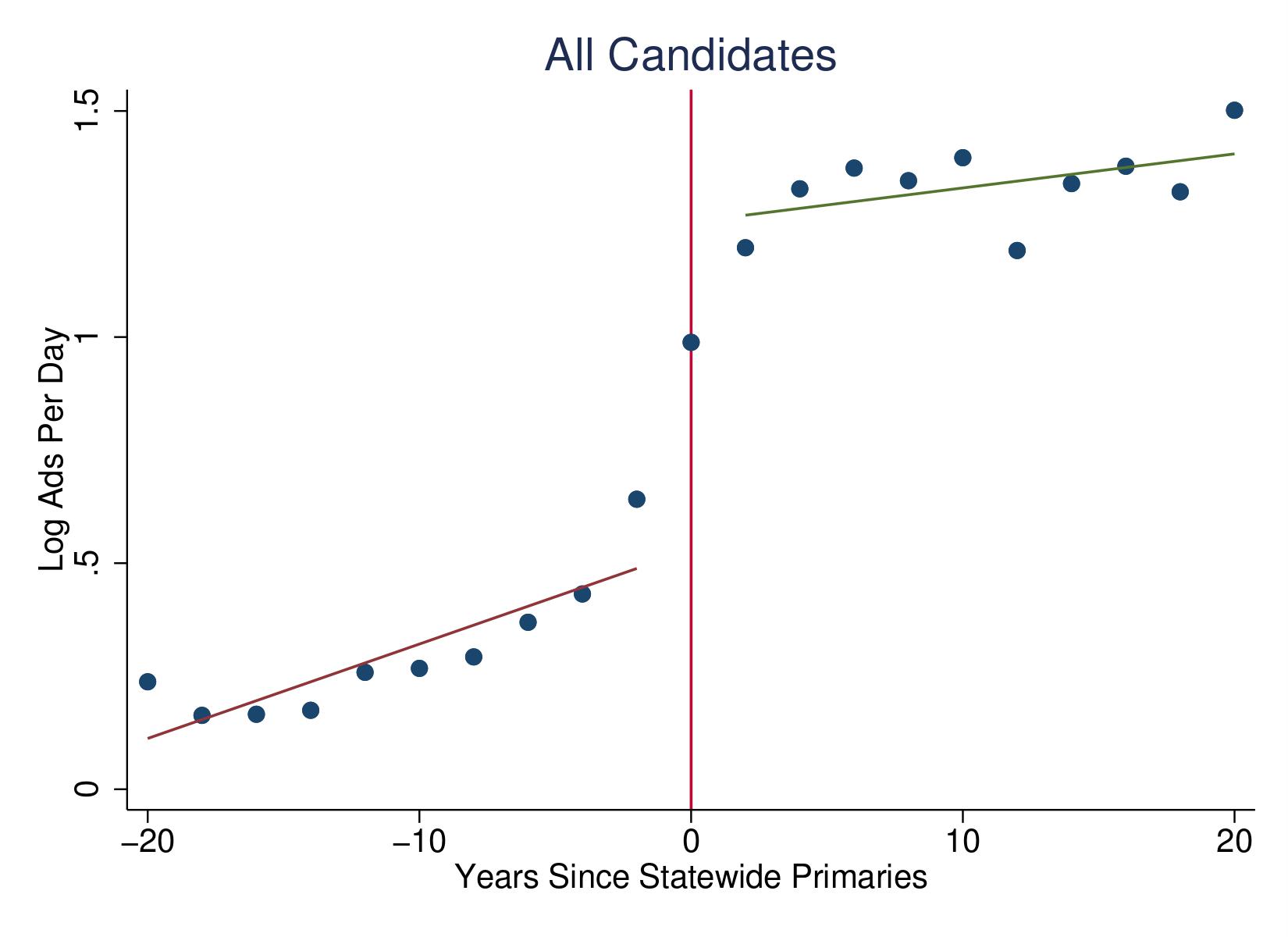

We use our measure of candidate newspaper advertising in a panel design, and find that candidate advertising increased substantially following the introduction of the direct primary. In fact, the introduction of primaries is associated with an increase in advertisements by about 220 percent. Further, the data suggests that a sharp increase in candidate advertising occurred around 1910 – substantially earlier than the conventional wisdom suggests. Figure 1 presents our results graphically by simply centering each state around the year of primary adoption and plotting candidate advertisements.

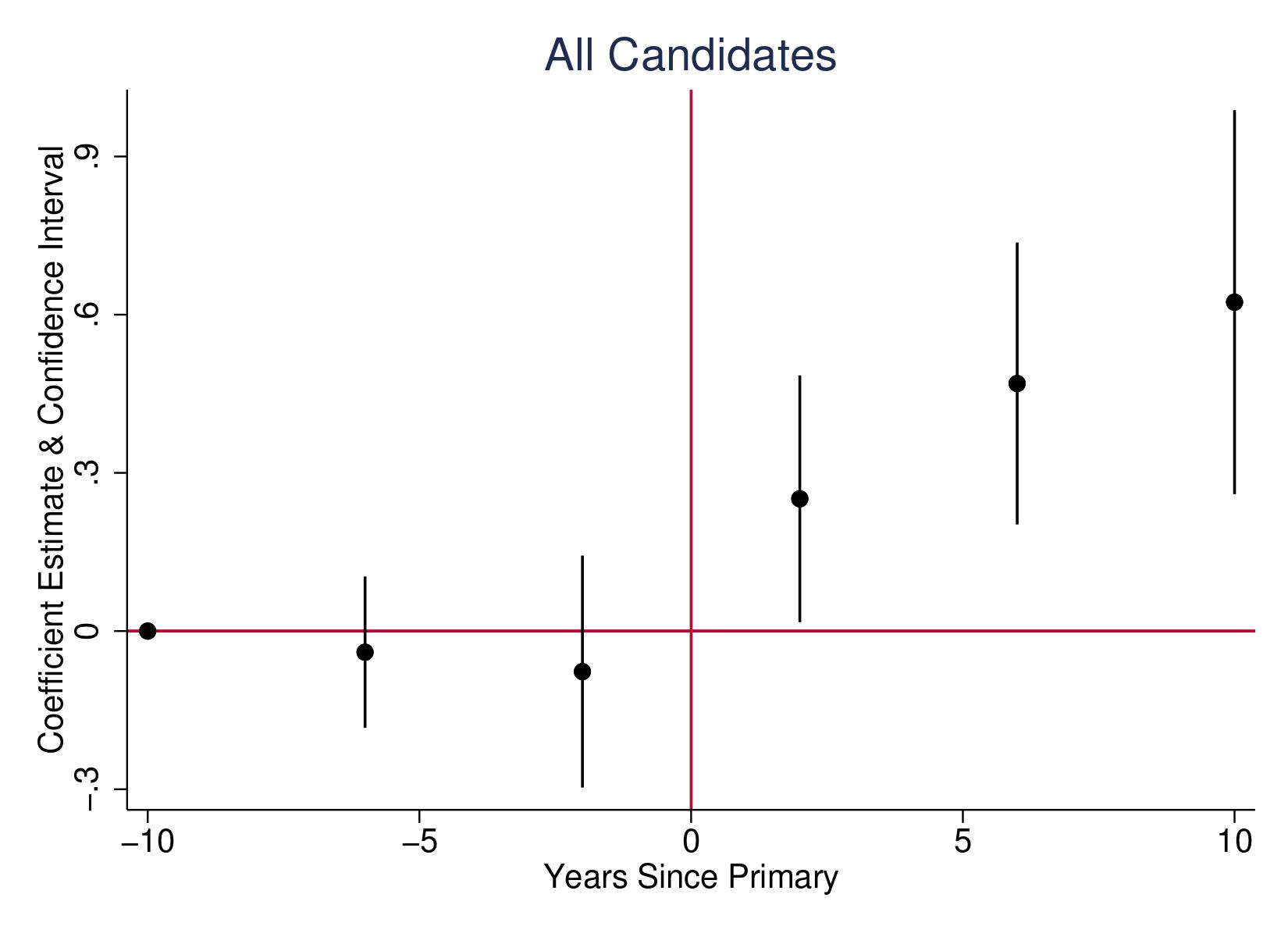

We also sought to better understand the longer term impacts of primaries. Primaries might have affected advertising via weakening party organizations, changing the pool of candidates, or changing voter attitudes towards parties and individual candidates. These changes are unlikely to have occurred immediately. Looking at groups of years before and after primary adoption, we find that the effects of primaries grew over time. Specifically, estimates for years 5 to 8 and years 9 and beyond are noticeably larger than the estimates for years 1 to 4. These results are presented in Figure 2.

Although our evidence suggests that the direct primary had important consequences for candidate centered campaigning, we do not find similar effects for the secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot. Almost all states adopted the Australian ballot between 1881 and 1896, granting Americans the right to vote out of the oppressing view of party bosses. Although this change is widely thought to have weakened party organizations, it does not appear that it impacted the advertising behavior of candidates.

To bolster our confidence in the strength of these findings, we also ran the models excluding candidates running for offices directly involved with the passing of the electoral reforms and divided the states into “early” versus “late” adopters. The estimated effects remain substantively similar, helping to address concerns about the role of states and legislators in passing the reforms.

Another important reform that occurred at a similar time was the switch to non-partisan elections. After this reform, certain offices no longer had parties listed next to candidate names in an attempt to decrease party influence over the office. To analyze the impact of non-partisan elections on the campaign environment, we re-run the same models as before focusing on elected judges. We focus on judges, because this office provides enough variation in enough states during 1880 to 1930 to estimate a reliable model. The results suggest that non-partisan elections had an even larger impact on the advertising behavior of candidates than primary elections. Our model implies an increase of 229 percent relative to the initial baseline of advertisements. However, it is important to reiterate that this model can only speak to judicial elections, and the results may differ for other offices.

Finally, we investigate how these progressive reforms impacted the types of candidates who advertise. Focusing on races for statewide offices, we find that candidates who faced primary competition advertised more than candidates who did not face primary competition. Additionally, candidates who were elected to a major office under the old system of elections ran more advertisements than new candidates, indicating that our results are not driven by a new batch of candidates who viewed campaigning differently.

This project draws on an extensive new dataset to offer an institutional basis for the twentieth century shift in American politics from party-centered to candidate-centered electoral politics.

A large body of work suggests that candidate-centered politics can lead to different policy outcomes than party-centered politics, including more district-oriented behavior such as constituency service and grant procurement. In addition to helping explain changes in the past, these findings provide helpful context for understanding today’s current political and partisan world.

This blog piece is based on the article “The Growth of Campaign Advertising in the U.S., 1880 to 1930” by Shigeo Hirano Jaclyn Kaslovsky, Michael P. Olson and James M. Snyder, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 3.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Shigeo Hirano is a Professor of Political Science at Columbia University. His research focuses on American politics, political economy and comparative politics, with a focus on elections and representation. You can find more information on his research here.

Jaclyn Kaslovsky is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rice University. Her research focuses on American politics, with specific interests in Congress, representation, and women in politics. A particular focus of her recent work is examining legislators’ – especially Senators’ – self-presentation and “home style” in their districts. You can find more information on her research here and follow her on Twitter: @JKaslovsky

Michael Olson is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis. His research focuses on the relationship between electoral and legislative institutions and legislative representation in the United States. Particular interests include the effects of party competition, the consequences of electoral and legislative reforms, and the central importance of the right to vote. Check out his website for more information and follow him on Twitter: @michael_p_olson

James M. Snyder, Jr. is the Leroy B. Williams Professor of History and Political Science in the Harvard Department of Government, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His primary research interests are in American politics, with a focus on political representation. He has written on a variety of topics, including elections, campaign finance, legislative behavior and institutions, interest groups, direct democracy, the media, and corruption. For more information, click here.