Some of the most contested, passionate, and often violent political conflicts often concern issues that have no apparent tangible value to the disagreeing parties. An attempt to remove a Civil War memorial in Charlottesville prompted deadly clashes on the streets. A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Congress and President Donald Trump found the time to battle over whether military bases can be named after Confederate generals.

The preponderance of conflicts over symbolic issues seems at odds with the conventional view that sees politics as a conflict over resources and power. A great deal of political capital is spent on deciding how to name streets, how to color flags, which monuments to erect or remove, how to interpret history, and what body positions athletes should take when a national anthem is played. Why do conflicts over symbolic matters become politically salient? Do such conflicts have measurable political repercussions?

The signaling power of symbolic politics

In our forthcoming paper, we theorize that conflicts over symbols matter because they are opportunities for competing groups to test and signal their power. By imposing its will on an issue — even if that issue is only symbolic — a group will appear more powerful. In and of itself, there may be no difference whether, for example, the national flag is red or green, but a group that manages to impose the green flag will appear more powerful. The desire to signal power incentivizes people to fight over the color of a flag even though intrinsically they may not care about it.

During the rule of Hafez al-Asad, Syrians routinely engaged in nauseating praises to their leader, without believing their own words. The regime incentivized these symbolic rituals of adulation not because it enjoyed hearing hypocritical praises, but because these rituals allowed the regime to project its awesome ability to submit people to its will. Or consider Vaclav Havel’s famous description of a greengrocer who diligently displays slogans of devotions to the communist regime in Czechoslovakia. The grocer did so not out of conviction, but to signal “his preparedness to conform”; if many others engage in this symbolic show of conformity, it “reinforces the perception that society is solidly behind the Party.”

If symbolic change signals a shift in the de facto distribution of power, what sort of reaction should it generate? Building on the status-threat logic, we hypothesize that the “losers” of a conflict over symbols will be mobilized to counteract the shifting distribution of de facto power. When they map onto partisan cleavages, conflicts over symbols impact competition over votes by mobilizing turnout within the “losing” group. In short, changing the symbolic status quo should mobilize a backlash.

Empirical test

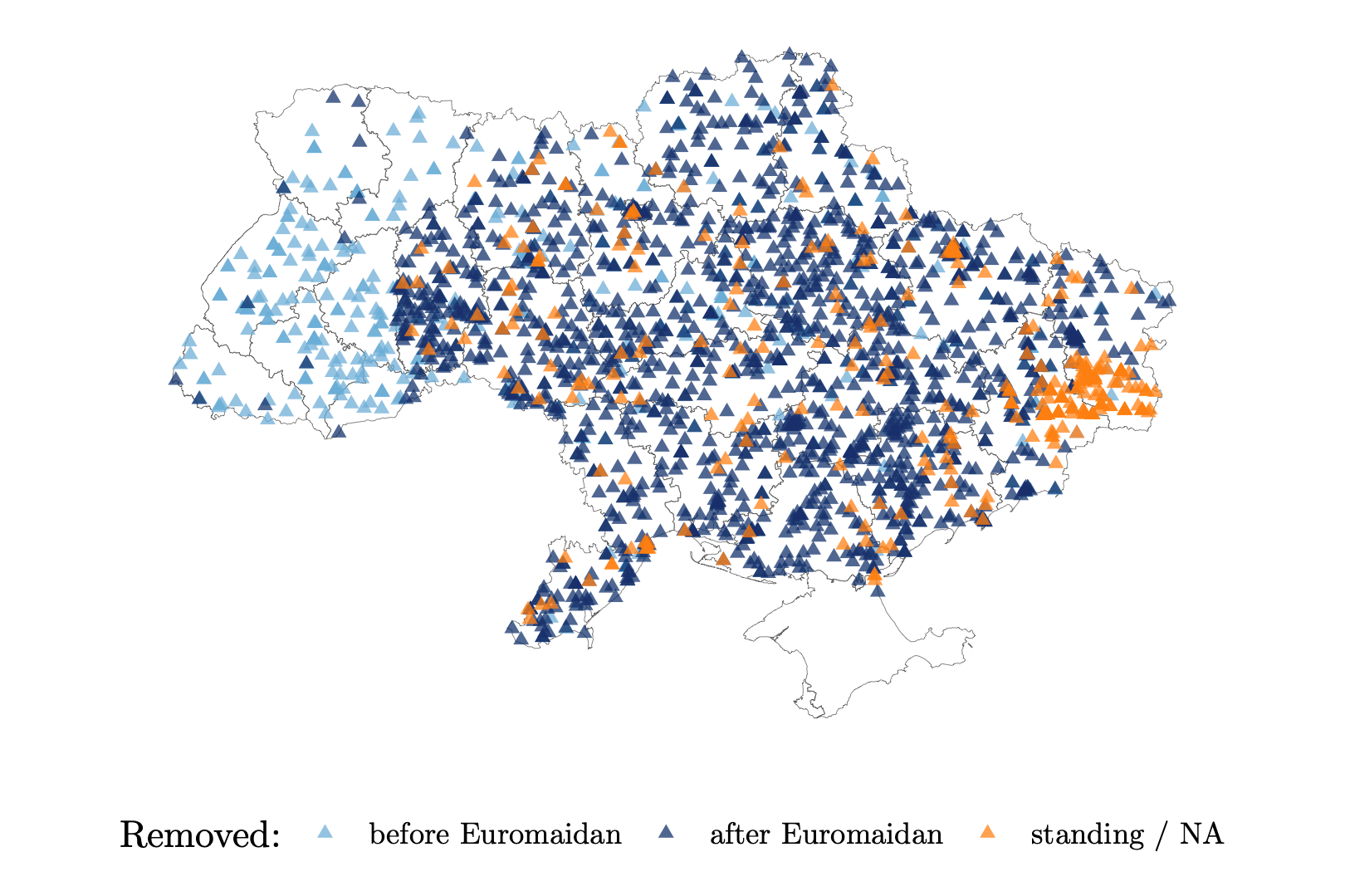

To put our theory to a test, we study the case of Leninopad in Ukraine. Leninopad (“Lenin’s free fall”) refers to the sudden wave of removals of Lenin’s statues that started during Euromaidan protests in late 2013. We collected data on 2,410 monuments to Lenin erected by the Soviet regime, shown in the map below.

We used these data to determine whether the removals of Lenin’s monuments impacted election turnout and, in particular, whether they impacted turnout among the supporters of the “pro-Soviet” candidates and parties – those that espoused views sympathetic to Ukraine’s Soviet past and were publicly opposed to Leninopad.

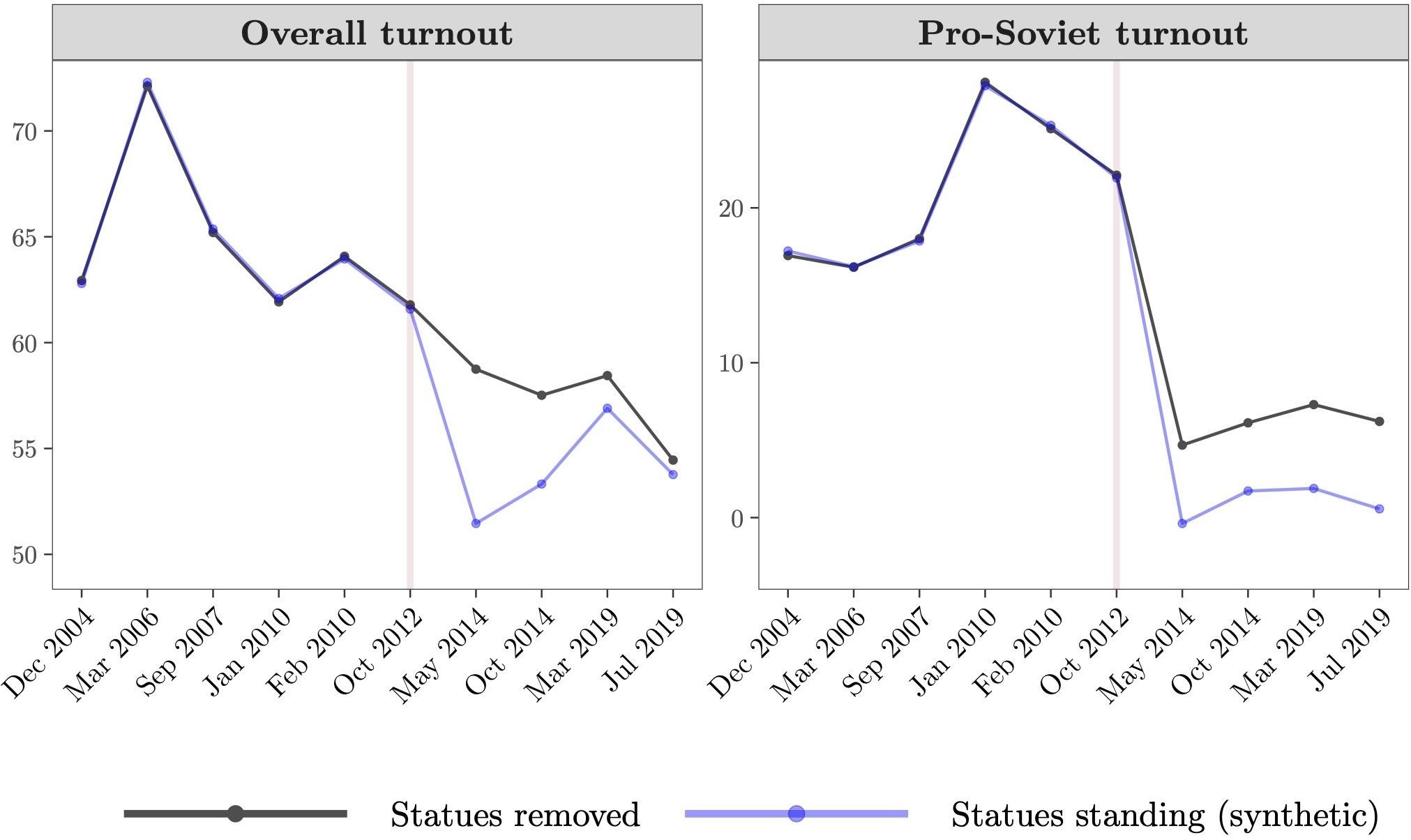

Below we show how election results changed during ten rounds of presidential and parliamentary elections held on the indicated dates. The black curves show turnout figures in the precincts where Lenin’s statues were standing prior to Euromaidan, but were removed before the May 2014 elections. The blue curves show the respective figures in precincts that also had Lenin’s statutes prior to Euromaidan, but those statues remained standing during the May 2014 elections. To ensure that we are comparing apples-to-apples, the precincts in the latter group were selected to maximize similarity to the first group.

Across all elections that preceded Euromaidan (up to October 2012), there were no practical differences between the precincts where statues were removed and those where they remained standing. But after Leninopad began, we see noticeable divergence: there was significantly more turnout in general and turnout among the “pro-Soviet” voters, in particular, following the removals of Lenin’s statues. By our most conservative estimates, the pro-Soviet turnout would have been about 1.6 percentage lower had the statues been left standing.

Overall, Leninopad led to greater turnout among those who opposed breaking with the Soviet past. Voters, mobilized by Leninopad, were threatened by the diminishing influence of politicians who sympathized with the Soviet legacy, favored closer ties to Russia, and had previously managed to thwart the attempts to remove Lenin’s statues.

When does symbolic politics matter?

When we looked at the subsequent elections that took place after May 2014, we did not find any effect of statute removals on turnout. Among multiple explanations of this pattern that we considered, the strongest one seems to be that when Russia escalated its proxy war in Ukraine’s eastern region of Donbass in the summer of 2014, Leninopad ceased being a divisive partisan issue.

We arrived at this conclusion by analyzing how the narratives on Ukraine’s Soviet past have shifted in Ukrainian media. Before the war, Lenin tended to be discussed in the context of divisive partisan politics. After the war escalated, the emphasis shifted: the symbols of the Soviet past began representing support for Russian military aggression and a threat to Ukraine’s state sovereignty. It became increasingly difficult for anyone to oppose Leninopad without appearing as a supporter of Russia’s war. As a result, removals of Lenin’s statues stopped provoking a backlash. It would seem that symbolic politics matter only when the symbols are divisive along the partisan lines.

Lessons for the current war

On February 24, 2022, Russia began a full-scale invasion of Ukraine by expanding the geographically limited war that it started in 2014 onto the entire territory of Ukraine. A key assumption behind Russia’s plan seems to have been that Ukrainians would welcome the invasion. As we know now, the Russian leadership has completely misread Ukraine.

Our paper shows that already in 2014, Russia’s military assault on Ukraine motivated Ukrainians to break away from their Soviet past – even those who previously opposed Leninopad became supportive or at least neutral towards it. Breaking from the Soviet past in Ukraine inevitably meant breaking away from Russia, where the Soviet past has never been critically confronted. The leadership of Russia and its intelligence agencies failed to see just how different Ukraine has grown from Russia.

This blog piece is based on the article “The Real Consequences of Symbolic Politics: Breaking the Soviet Past in Ukrain” by Arturas Rozenas and Anastasiia Vlasenko, will be published in July 2022 issue.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Authors

Arturas Rozenas is Associate Professor in the Department of Politics at New York University. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science (Duke, 2012) and MS in Statistical and Decision Sciences (Duke, 2010). In 2016-2017, he was a National Fellow at Hoover Institution, Stanford. His research focuses on authoritarian politics, information manipulation, state repression, and historical legacies. His empirical work mostly covers Ukraine and Russia. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @a_rozenas

Arturas Rozenas is Associate Professor in the Department of Politics at New York University. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science (Duke, 2012) and MS in Statistical and Decision Sciences (Duke, 2010). In 2016-2017, he was a National Fellow at Hoover Institution, Stanford. His research focuses on authoritarian politics, information manipulation, state repression, and historical legacies. His empirical work mostly covers Ukraine and Russia. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @a_rozenas

Anastasiia Vlasenko is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at Florida State University. From 2014 to 2016, Vlasenko was a Fulbright scholar at New York University. From 2020 to 2021, she worked at Hertie School in Berlin as a visiting researcher. Her main research focus is electoral politics and democratization with a specialization in the politics of Ukraine and Russia. She is particularly interested in transitional period reforms, propaganda, electoral politics, and forecasting. At FSU, Vlasenko teaches courses on comparative politics and post-Soviet studies. You can find further information regarding her research here and follow her on Twitter: @anastvlasenko