Democracies are littered with imprints from their authoritarian pasts. Authoritarian-era successor parties and politicians often remain on the scene and retain influence. This can lend an air of artificiality or unfairness to democracy. But even if authoritarians can navigate the tricky path to democracy and avoid prosecution, it does not mean that they remain untouchable. Citizens live with their experiences from the authoritarian past. Those experiences shape how people perceive democracy, who they vote for, and how they associate with one another. My research, based in Spain in the decades after its transition from fascism to democracy, shows that voters can hold authoritarian successors and their ideologies accountable for their past records.

Tools of Authoritarian Control

Authoritarian governments around the globe aim to control their populations and maintain political stability. The tools they use to do so are wide-ranging, from mass repression to institutional co-optation and other non-violent strategies of control. Of course, the expansion of democracy over the last century shows that authoritarianism can still crumble.

Scholars are just beginning to understand how experiences from living under the thumb of authoritarianism impact people’s political behavior and voting. The area of most active research to date in this area focuses on repression. It is clear from this research that repression triggers an enduring reaction against political groups and ideologies associated with the perpetrator of repression.

But mass repression as a tool of control is risky and rarely used given that it can cause a backlash. By contrast, non-violent policy-based strategies of control are legion among authoritarian regimes. Far less is known about how citizens evaluate and react to these policies once they are able to express their preferences freely at the ballot box without fear of reprisal.

Spain’s Authoritarian Land Settlement

I studied political behavior in areas of fascist-era land settlements in Spain to evaluate how settlers’ experiences under authoritarianism informed their later voting patterns after the country transitioned to democracy. In the aftermath of a brutal civil war in the 1930s that was sparked in part over land reform and broader agrarian issues, Spain’s new leader, General Francisco Franco, launched an ambitious land settlement program. It aimed to settle arid lands, irrigate them where possible, and turn them into farming villages by relocating nearby agricultural laborers in them.

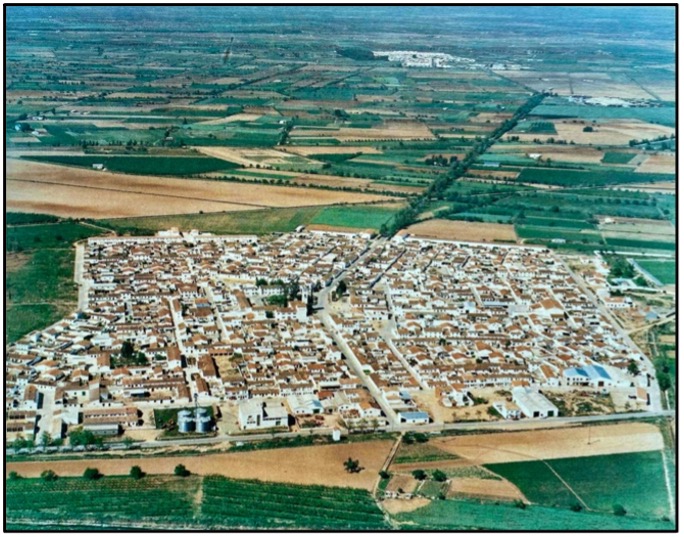

The program constructed nearly 300 new villages and built over 30,000 houses. It built dams and channels, dug irrigation ditches, constructed infrastructure like roads and electricity, and installed aquifers. The government spent the equivalent of 20 billion euros and hired renowned architects and construction firms to design and build housing, towns, and infrastructure. It came to encompass nearly one million hectares of land, a reform roughly equal in size to Italy’s post-WWII land reform. The image of Valdelacalzada in Badajoz province illustrates one of these new towns.

At its core, the Franco regime sought to control settlements and settlers. Settlement policy was a tool for achieving rural political stability and quiescence while increasing agricultural production. Three defining elements were settler indebtedness to the government, incomplete property rights over land and housing, and paternalism from state bureaucrats and agents. The government used these policy features to leverage dependency, increase the cost of disloyalty, and facilitate control.

Citizens’ Reactions to Authoritarian Control

Although settlers received land, housing, and inputs, generating initial optimism and enthusiasm, over the course of decades they came to suffer from fear of losing those benefits, shame linked to indebtedness and state paternalism, and anger sparked by the capriciousness and arrogance of bureaucrats. They expressed this politically once Franco lost power and democracy arrived by voting against the political parties most closely linked with the authoritarian past and in favor of the chief opponents of these parties.

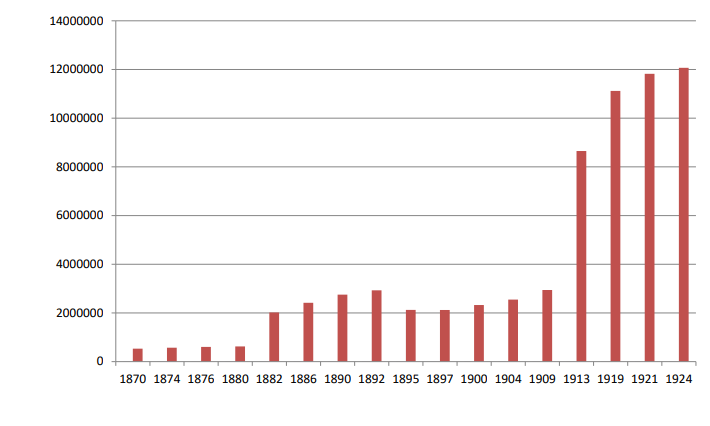

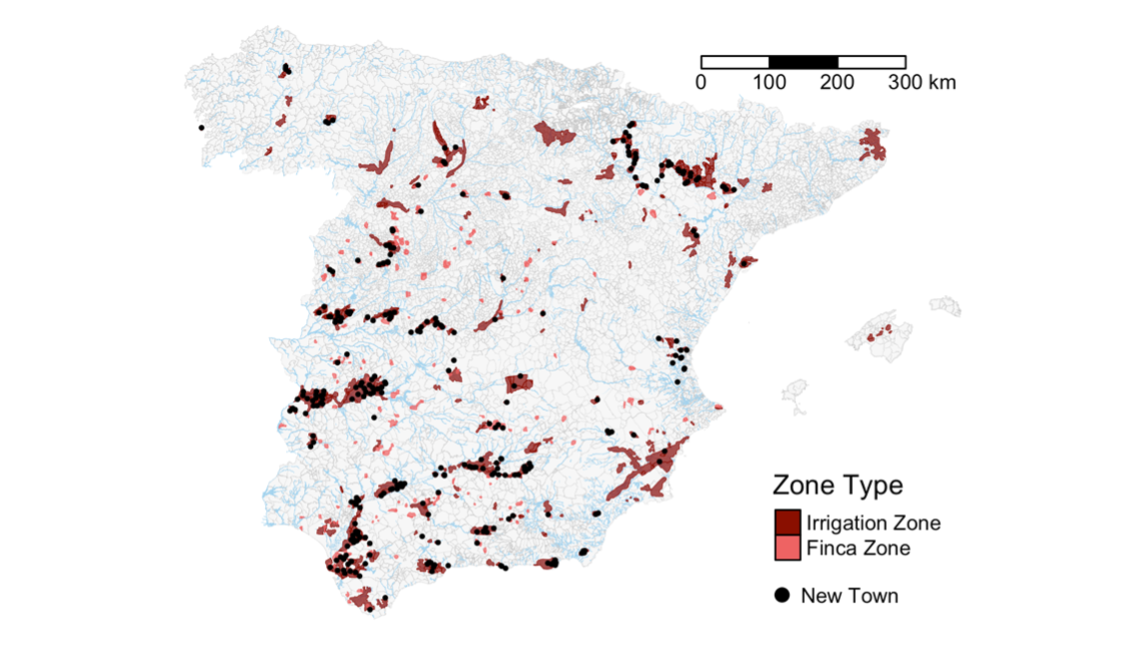

To draw this conclusion, I examined data on land settlement zones, newly settled towns, and the vote share of Spain’s main political parties that inherited the Francoist legacy and their leftist political opponents. The map of Spain here illustrates that these zones (there were two related types known as irrigation zones and finca zones) and settlement towns were spread across the country. Key to my analysis is the fact that while there were strong geographic determinants of the zonal areas targeted by the government for settlements, areas within zones were akin to a blank slate from the perspective of creating new settlement towns. There were no discernible differences in social, economic, or demographic factors within these relatively small and homogeneous zones prior to settlement. The government could design projects within a given zone in many ways. I compared municipalities within settlement zones where towns were built to municipalities within settlement zones where no towns were built to verify this.

I then matched municipalities with new settlement towns to otherwise similar municipalities within settlement zones where no towns were built on the basis of geography, agricultural suitability, demography, and state capacity. This yields groups of similar “treatment” and “control” municipalities. These groups also had no substantial pre-settlement political differences in political factors.

Despite their initial similarity, these two groups of municipalities diverged politically after Spain’s return to democracy. Leftist vote share was higher in municipalities with new government-created towns. New town treatment is associated with a 3.6-4.3 percentage point increase in voting for the left relative to control municipalities in the 1977-1982 elections. This effect diminishes over time but lasts into the early 1990s. It is especially pronounced where settlers in new towns were numerous relative to other local populations. Additional analysis as well as qualitative accounts from settlers and bureaucrats suggests that this effect is driven by settler reactions to authoritarian social control.

Lessons for Democracy

Negative electoral headwinds from past policies can counteract some of the advantages that authoritarian successors typically have in terms of their organizational prowess, governing experience, and material stature. And it can force successors to put on a new face, switching out the old guard and bringing in new, often younger politicians that may be less connected to the past and have stronger incentives to play by new democratic rules. That can be a real benefit to democratic competitiveness and consolidation.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “The Political Price of Authoritarian Control: Evidence from Francoist Land Settlements in Spain” by Michael Albertus.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the Author

Michael Albertus is a professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. His research examines democracy and dictatorship, inequality and redistribution, property rights, and civil conflict. His most recent book is Property Without Rights (Cambridge University Press, 2021). Follow him on Twitter: @mikealbertus