In the era of European colonialism, Christian missionaries spread to practically every corner of the globe. By 1900, they had evangelized 700 million people, nearly half the world population.

The conventional wisdom in the social science literature is that Protestant missionaries spread literacy and democracy. The argument is straightforward: Protestant missionaries founded thousands of schools around the world. partly for the self-interested reason that they wanted a population that could read the Bible. Missionary schools spread literacy — and in doing so sowed the seeds of democracy and social reform movements.

However, my co-author Chen Ting and I thought that this perspective only told part of the story. In many places — including the country where we do most of our research, China — missionary activity came to symbolize western imperialism. In China, missionary activity sparked anti-foreign protests, anti-missionary riots, and the spread of new ideas about what it meant to be “foreign” and “Chinese.”

Did backlash to missionary activity spark nationalist mobilization? For a new paper, Ting and I collected quantitative data on missionary activity, anti-missionary violence, and nationalist secret societies in China. But first we looked to the archives.

Archival Evidence Illustrates the Nationalist Backlash to Missionaries

In 1886, in the city of Chongqing in southwestern China, dozens of students gathered to take the imperial exam. Taking and passing the imperial exam was the key path to political power in China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The select few who passed the exam would earn prestigious and lucrative spots in the state bureaucracy. Exam takers would have been preparing their whole lives for this day, and their families would have invested considerable resources in getting to this point.

Yet instead of taking the exam, the students flooded to the streets, burning down buildings and chanting slogans. Their target? Foreign missionaries. Missionaries in Chongqing had been acquiring land to build churches, against the wishes of many local elites. Rumors were spreading that missionaries protected and harbored criminals, and that they had insulted locals and traditional Chinese beliefs.

The Chongqing riots of 1886 were just one of hundreds of such incidents throughout China in the late 1800s. In our research, we came across detailed descriptions of dozens of incidents in Sichuan alone, something that a number of historians of China — notably Xiaowei Zheng, whose excellent recent book we build on — have written about previously.

Local elites used several tactics to mobilize the community against missionaries. One important tactic was the use of anti-foreign propaganda. Above is a picture from a pamphlet distributed a few years after the Chongqing riots. The image depicts a member of the local gentry encouraging people to take revenge on missionaries. Other images in the pamphlet show Christian missionaries torturing and mutilating victims, or engaging in devil worship, in a way that is plainly calculated to inflame tensions.

Qualitative accounts show how hundreds of anti-missionary incidents contributed to the rise of nationalist ideas and nationalist organization. For example, a man named Zhu De — who would later earn fame as a Party general and leader — told his biographer that his political awakening came as a young boy when he learned about the 1886 Chonqing riots. When asked by his biographer why he did not go to a missionary school, Zhu replied: “How could I? I was a patriot! The missionaries turned Chinese into political and cultural eunuchs who despised their own history and culture.” Zhu would go on to join a nationalist secret society called the Tongmenghui.

Missionaries and the Rise of the Tongmenghui

The Tongmenhui was the most important nationalist organization in late Qing China. It was founded in 1905 by Sun Yat-Sen, who is often regarded as the father of the Chinese nation. Sun’s organization brought together several competing secret societies under one roof, with the aim of reviving China and ousting the Manchu-led Qing government. To be sure, the Tongmenghui was not the only nationalist organization of the era, but it was almost certainly the most notable, and in the end it did play a role in the fall of the Qing.

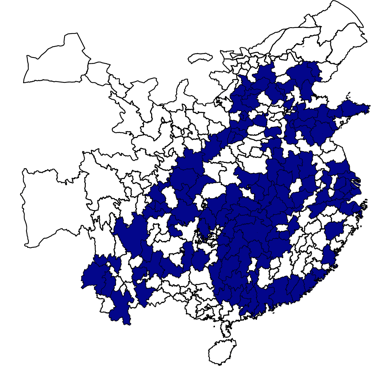

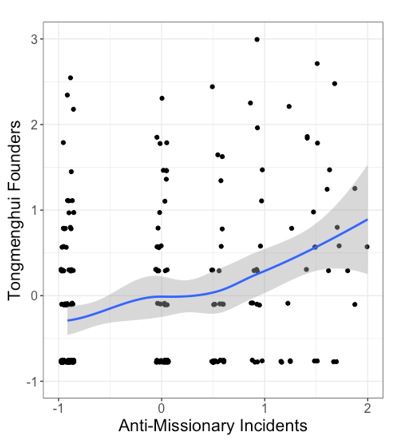

To understand whether missionary activity might have influenced the spread of nationalist ideas in general, and the Tongmenghui in particular, Ting and I collected new data on the origins of all founding members of the Tongmenghui. We were inspired by a paper that we both admire by Bai Ying and Ruixue Jia, which showed that the abolition of the imperial exam led disgruntled young elites to join the Tongmenghui. We think their argument is likely correct but that the abolition of the exam was just one of several causes of nationalist mobilization. We also noticed that their dataset missed 395 out of 895 members of the founding members of the Tongmenghui. We collected comprehensive data on all Tongmenghui founders, as well as data on 450 anti-missionary incidents and on the spread of missionaries.

Consistent with the idea that missionary backlash and nationalist ideas are linked, we found a robust correlation between missionary incidents and the number of Tongmenghui founders. The more missionaries or the more anti-missionary incidents, the more Tongmenghui members a locality produced.

In the full version of our paper, we delve deeper into both the theory and a stronger research design that probes whether this correlation might reflect a causal relationship.

Conclusions

Our argument goes against the prevailing narrative in the historical political economy literature, which has more often focused on how missionaries spread schooling, literacy, and democracy.

From a certain angle, the missionary enterprise, which touched the lives of half the world population by 1900, could be thought of as one of the largest social engineering efforts in modern history. And it was not always a success.

A rich literature in historical political economy has examined the legacy of colonial rule. Much of this literature has focused on what states and state bureaucrats did. However, there has been somewhat less research unpacking the legacy of missionary activity. This remains an important avenue for future research.

This post is reprinted from the Broadstreet, a blog dedicated to research on historical political economy.

This blog piece is based on the article “The Missionary Roots of Nationalism: Evidence by China” by Daniel Mattingly and Ting Chen, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, July 2022.

The empirical analysis of this article has been succesfully replicated by the Journal of Politics and replication materials are available at the The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the authors

Daniel Mattingly- Yale University

He is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Yale University. His research focuses on the politics of authoritarian regimes, historical political economy, and China. You can find further information regarding his research on his website and follow him on Twitter @mattinglee.

Ting Chen- Hong Kong Baptist University

She is an associate professor in the Department of Economics at the Hong Kong Baptist University. Her research interests encompass diverse topics in the broad areas of long-term historical development and the contemporary Chinese political economy. Inspired by the complex relationship between institutions, culture, and long-run economic growth, she has studied the origins of China’s meritocratic civil exam system (keju), long-run human capital development, cultural (religious) conflicts between the east and the west, political promotion, political connections between firms and officials, and corruption more broadly. You can find further information regarding her research on her website and follow her on Twitter @colomct.