Worldwide, women are underrepresented in politics. According to The World Bank, as of 2022, only 26 % of seats in national parliaments were held by women on average. With an increasing number of women entering the workforce and growing support for gender equality in society, this disparity in representation is particularly striking.

In our recent article published in The Journal of Politics, we investigate the role political parties play in maintaining and exacerbating the gender gap in political representation, focusing on how parties utilize their apparatus to support men and women candidates during the campaign. We show that when parties are made stronger, they often use their newly acquired resources to disproportionately foster the political careers of men.

When Will Parties Contribute to Reducing Women’s Representation?

In the realm of political science, strong parties are associated with many desirable goals, including greater citizen participation, responsive governments, and political stability. For this reason, the transformation of parties from weak — where individuals’ self-interest prevents the party from achieving its collective goals — to strong is expected to improve the quality of democracy. In relatively newer democracies, where many parties lack strong organizational capabilities and party labels are weak, attempts to increase party strength are received with optimism.

In our study, we argue that increasing the strength of parties does not necessarily lead to strictly positive results. Instead, it can have negative consequences for the representation of women when parties are not committed to gender equality. As parties become better able to manage their members, their pre-existing priorities are more likely to be transformed into reality. If parties are highly focused on advancing the careers of one group within the party, greater organizational capacity will put them in a better position to do so, thereby intensifying discrepancies.

Using data from Brazil, we demonstrate that as parties grow stronger, the disparity in electoral performance between men and women increases.

Why Study Parties in Brazil?

In Brazil, the Supreme Court has taken action to strengthen parties, largely motivated by the goal of improving democracy. In a 2007 ruling, it declared that elected officials would lose their office if they decided to switch parties. As a consequence, parties were able to retain local-level politicians within their ranks, who are crucial in garnering votes for their candidates in federal elections. This court ruling provided us with a unique opportunity to study the effect of increasing party strength on women’s electoral prospects.

Furthermore, Brazil’s 5,500+ municipalities allowed us to thoroughly investigate how parties utilize their now reliable network of mayors, who are prominent figures in local politics, to disproportionately assist male candidates running for higher-level office in garnering votes compared to women. The extensive number of municipalitie–all governed by the same electoral rules–enabled us to estimate how parties use their network differently in supporting male and female candidates in their campaign efforts, while also accounting for other factors that could influence this gap, including party support in the municipality.

Stronger Parties May Harm Women’s Electoral Performance. Why?

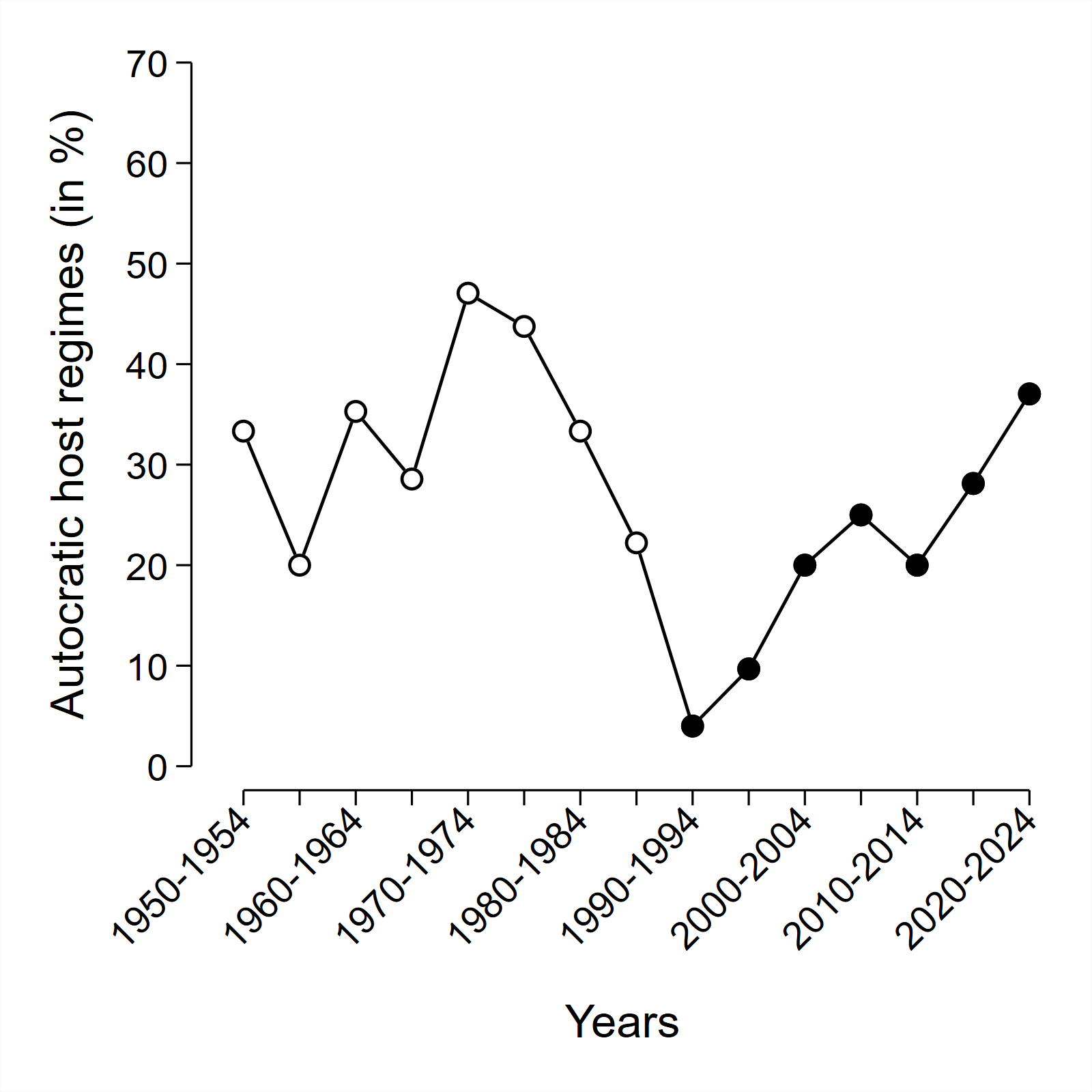

Political parties are still largely composed of and led by men. Our study emphasizes that as political parties gain strength, they frequently prioritize advancing the political careers of those who are already prominent within the party, typically men. As depicted in the figure, during the period when parties could rely on local-level politicians to campaign for their candidates (2010-2014), the voting gap between men and women widened. This contradicts the belief that stronger parties inherently promote democratic goals. At least in the short term, the transition of parties from weak to strong can intensify exclusionary patterns against historically marginalized groups.

Although the precise mechanism as to why local-level copartisans only assist male political aspirants has yet to be elucidated, existing work in political science provides some guidance on why this might be the case. For example, in addition to blatant discrimination solely on the basis of gender, men may be less likely to believe that women are competitive enough to ultimately win, or more likely to have other men in their immediate professional circle.

Implications

Taken together, our findings shed light on the impact of institutional engineering, showing that achieving better representation for women requires targeted actions, such as implementing gender quotas and ensuring fairness in campaign resources. Put simply, merely strengthening political parties will not necessarily improve conditions for women unless parties actively prioritize gender equality alongside other objectives.

Note

Figure: Effect of copartisan mayor on men and women candidates’ vote share. When parties could reliably count on mayors to assist their candidates in obtaining votes (Strong Electoral Rule Regime), a gender gap in votes emerged, with men benefiting more from the assistance of copartisan mayors than women.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Strengthening the Party, Weakening the Women: Unforeseen Consequences of Strengthening Institutions” by Andrea Junqueira and Patrick Cunha Silva.

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Andrea Junqueira is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Arkansas State University. She studies elections and representation. For more information, visit her website.

Patrick Cunha Silva is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Loyola University Chicago. He studies electoral systems, gender representation, and political campaigns. For more information, visit his website.