A defining feature of democracy is that voters reward or punish incumbents at the ballot box in response to the policies and general conditions that they observe. By doing so, they can encourage politicians to implement better policies. In times of crisis, this might not be that easy. Adopting adequate measures in response to an emergency can be challenging due to the implicit trade-offs between certain policies. The global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus has exemplified this in a devastating manner. Concerns regarding how to protect public health without harming the economy have been particularly salient.

It is thus not surprising that we have also witnessed a great deal of differences in responses adopted by different governments. For instance, many Western democracies have been less likely to impose stringent mitigation measures to stop or slow down the spread of COVID-19 than countries with authoritarian machineries. These remarks may be alarming. Are democracies well-suited to face epidemic outbreaks? Do politicians have an incentive to contain epidemics when public-health interventions may come with an economic cost?

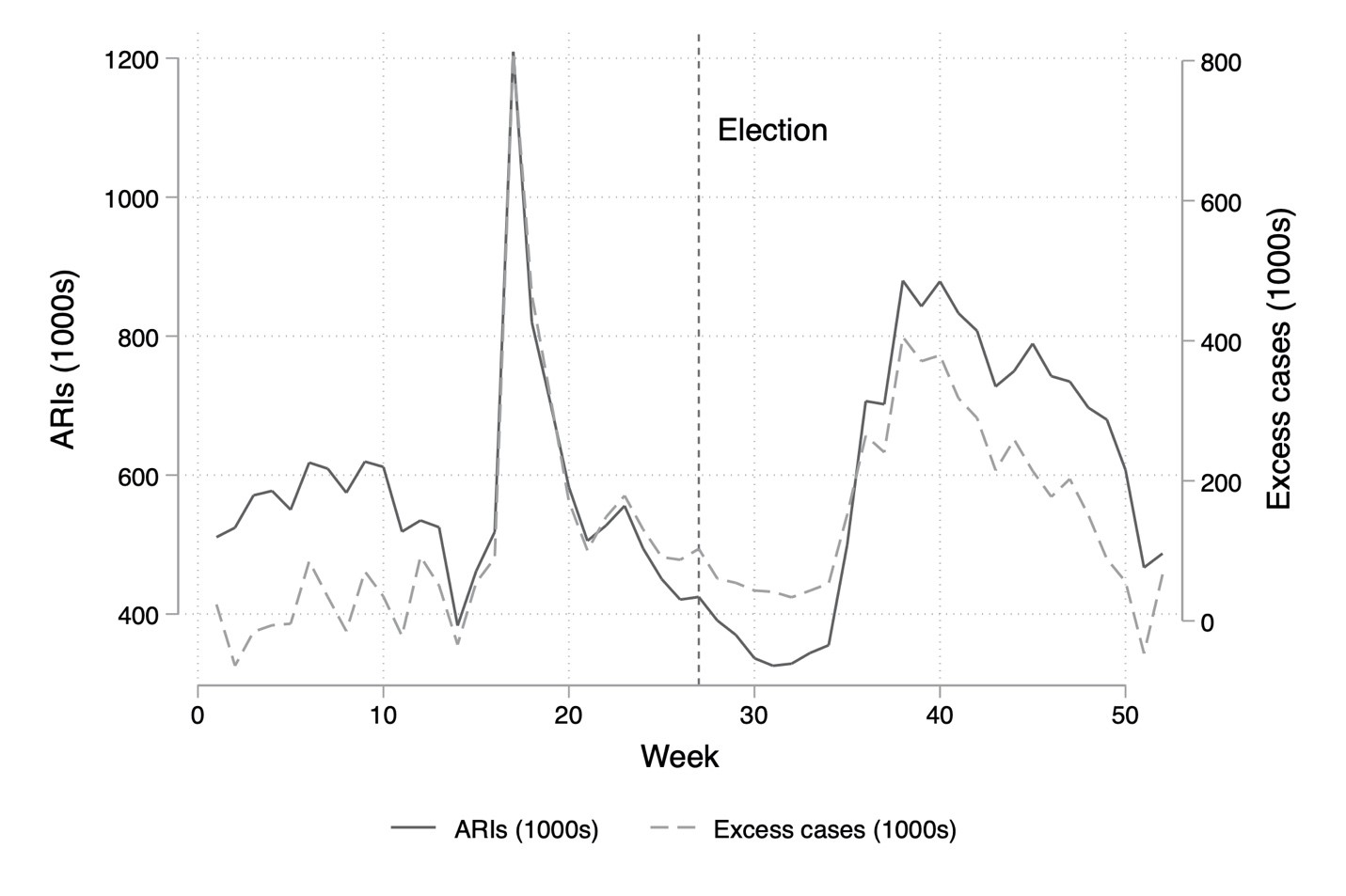

To shed light on these questions, we revisit the first pandemic of the 21st century and study the electoral impact of the 2009 H1N1 epidemic in Mexico. H1N1 was a large, unexpected, and generalized health shock. Its prevalence was widespread and individuals were indiscriminately exposed to it. The initial H1N1 outbreak occurred in Mexico in March 2009, with a large spike in excess acute respiratory infections at the end of April (see Figure 1). A couple of months later, when the first epidemic wave had largely subsided, the country voted in federal elections for the Congress. This was a stress test for the incumbent federal party, Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), as the pandemic response was solely coordinated by the federal government.

Figure 1. Acute respiratory infections diagnosed during the year 2009.

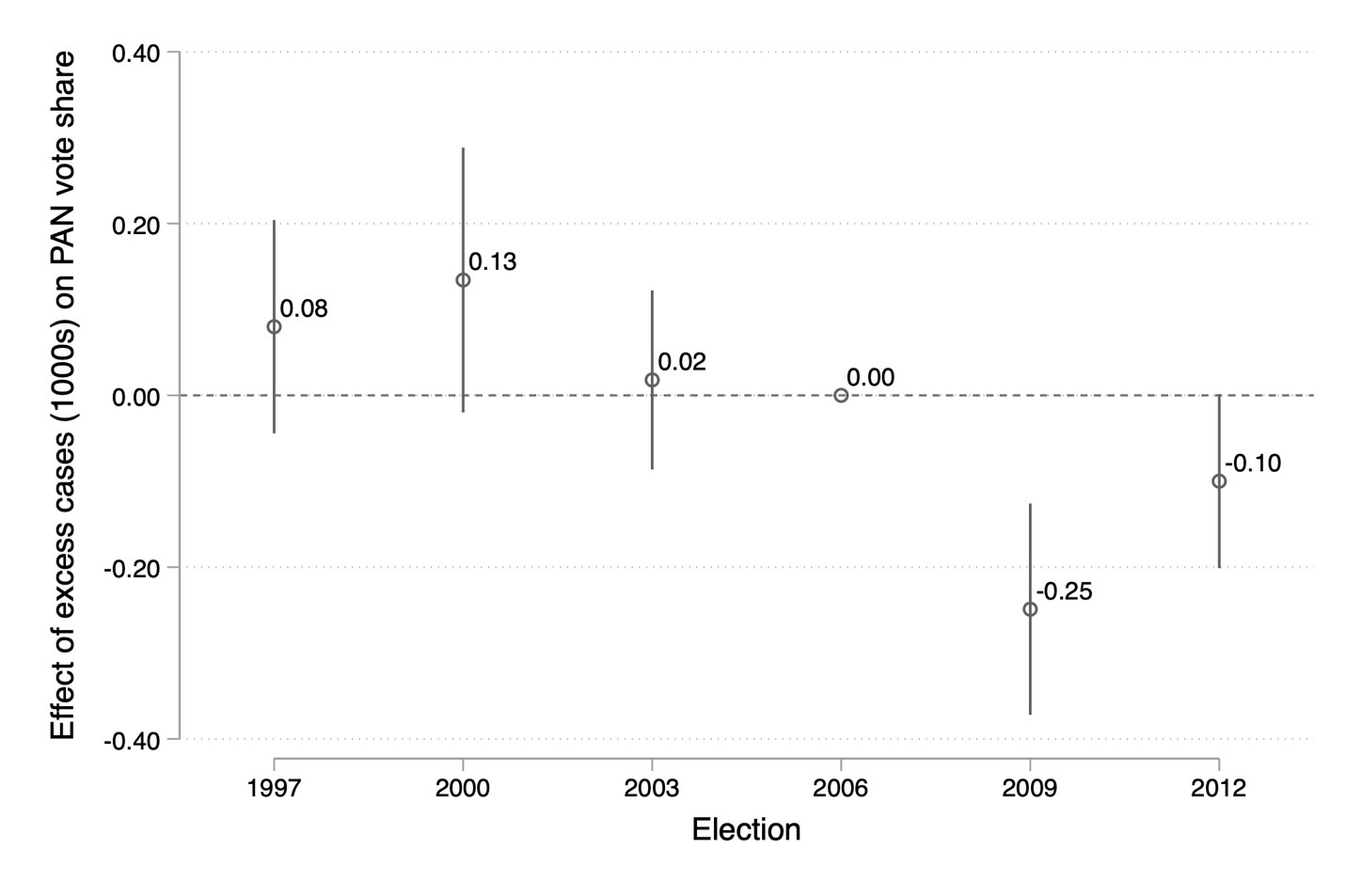

We ask whether support for the PAN was different in the 2009 legislative elections in the electoral sections—the smallest administrative unit in the country—that experienced a larger H1N1 outbreak relative to those where the outbreak was smaller. To achieve this, we combine detailed administrative data on electoral results with precise information on diagnoses of respiratory diseases in health facilities throughout the country. Our results reveal a strong negative relationship between the magnitude of the local epidemic outbreak—measured as excess cases of respiratory diseases relative to preceding years—and PAN vote share in the 2009 congressional elections (see Figure 2). One thousand excess are associated with an average decrease of 0.25 percentage points in the vote share for the PAN. What is more, the negative impact persisted at least until the 2012 elections. We estimate that a thousand excess cases induced a negative effect of around 0.10 percentage points on the PAN vote share in the 2012 election. The magnitude of these estimates is large enough to suggest that voter reactions to the H1N1 epidemic may have played a decisive role in the close electoral contests in 2009 and 2012.

Figure 2. H1N1 and electoral performance of the incumbent

Why did Mexican voters react to the pandemic exposure this way? We argue that voter learning is one key mechanism. We find that the electoral punishment was larger in places that saw a greater peak in cases and where voters had worse access to healthcare. It could be the case that voters used the information that was observable to them as a proxy for the effectiveness of the government’s response, or to learn about the competence of the governing party, punishing the federal incumbent when experiencing a larger caseload. Another factor at play appears to be voter turnout which has been a robust predictor of PAN’s electoral performance. In line with the idea that health risks can make voting more costly and encourage voters to stay home on the election day, voter turnout was negatively affected by the disease outbreak.

Although the emergence of the pandemic was out of the hands of the Mexican government, the response to it was not. Our results show that voters did not dismiss the negative local impact of the epidemic simply as bad luck. Rather than that, they seem to have used the data that they observed as an indicator of the effectiveness of the government’s response, punishing the incumbent party at the polls when they experienced a higher number of cases. This further implies that at least in some democratic settings, governments ought to have incentives to contain epidemic outbreaks, especially if they are concerned about their future electoral performance.

Our findings may be informative about the potential repercussions of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and other large-scale epidemic outbreaks. Indeed, there has been much public debate on how this pandemic has already shaped and will continue to influence electoral outcomes. Our example highlights that COVID-19 may contribute to political change in the short run but also influence electoral outcomes further ahead. However, given the unprecedented nature of the current pandemic, its political impacts may differ from those of H1N1 and will surely be studied by scholars of electoral behavior for years to come.

This blog piece is based on the article “Electoral Repercussions of a Pandemic: Evidence from the 2009 H1N1 Outbreak” by Emilio Gutiérrez, Jaakko Meriläinen, and Adrian Rubli, forthcoming in the JOP.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Emilio Gutiérrez (@emiliogf) is a Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research interests are development, health, and political economics. You can read more about his research here: https://www.emiliogutierrez.net/.

Emilio Gutiérrez (@emiliogf) is a Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research interests are development, health, and political economics. You can read more about his research here: https://www.emiliogutierrez.net/.

Jaakko Meriläinen (@jmerilainen) is an Assistant Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research focuses on electoral politics, political representation, and historical political economy. You can read more about his research here: https://sites.google.com/view/jaakkomerilainen/.

Jaakko Meriläinen (@jmerilainen) is an Assistant Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research focuses on electoral politics, political representation, and historical political economy. You can read more about his research here: https://sites.google.com/view/jaakkomerilainen/.

Adrian Rubli (@AdrianRubli) is an Assistant Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research aims at understanding how healthcare providers and health policies interact and shape population and market outcomes in developing contexts, in particular Mexico. You can read more about his research here: https://www.adrianrubli.com/.

Adrian Rubli (@AdrianRubli) is an Assistant Professor of Economics at ITAM in Mexico City. His research aims at understanding how healthcare providers and health policies interact and shape population and market outcomes in developing contexts, in particular Mexico. You can read more about his research here: https://www.adrianrubli.com/.