One of the most robust empirical facts in the political science literature is that children resemble their parents along with a number of political behaviors and attitudes. In this study, we focus on such parent-child similarities (or so-called intergenerational transmission) in voter turnout.

Differences in political participation related to family background carry special significance because they speak to the issue of the equality of political opportunity. According to this cornerstone of democracy, political influence should not depend on factors outside an individual’s direct control, such as who their parents are. Indeed, inherited political inequality brings us uncomfortably close to the type of political regimes against which democratic revolutions were once fought. Political mobility within and between generations, thus, is an important quality of a well-functioning democracy, facilitating the equalization of political influence across individuals and families.

Against this background, this study sets out to increase our understanding of the mechanisms causing persistent intergenerational similarities in voter turnout. We use unique population-wide register data from Sweden, including validated turnout information from four national elections held between 1970 and 2010. First, based on more than 4,000,000 parent-child pairs, we find having parents who voted in previous elections boosts their offspring’s likelihood of voting in the current election by 23 percentage points. This sizeable effect is on par with the strength in parent-child voter turnout transmission found in other Western countries.

More importantly for our purposes, though, is that the underlying causes of correlations between biological relatives are observationally equivalent since parents both provide a rearing environment for and transmit a set of genes to their children. A voluminous literature in political science utilizing traditional twin designs has documented a substantial amount of genetic influence on a wide range of attitudes and behaviors, including political participation and voter turnout.

These twin-study findings raise the possibility that the intergenerational association in political voter turnout we report is partly accounted for by genetic endowment, a factor that has been largely ignored in previous research on parent-child similarities in political traits. To address this issue, we use a subset of our data including all native adoptees and their biological and adoptive parents. The quasi-experiment of adoption effectively breaks the genetic link between parent and child and allows us to use the data to decompose the overall intergenerational transmission in turnout behavior into a genetic and a social pathway.

The logic here is simple. A positive correlation in turnout behavior between the birth parents’ and their adopted-away children must be due to genetic or biological factors. We call these pre-birth factors. Correspondingly, a positive correlation in turnout behavior between the adoptive parents’ and their adopted children must be due to social factors such as different social learning mechanisms in the rearing environment. We call these post-birth factors.

Our adoption sample includes more than 10,000 adoptees for whom we also have information on their biological and adoptive parents. Using this sample, we show that the pre-birth factors explain one-third whereas post-birth factors account for two-thirds of the parent-child similarity in voter turnout. That is, the intergenerational association in voter turnout can be traced to both genetic and social sources.

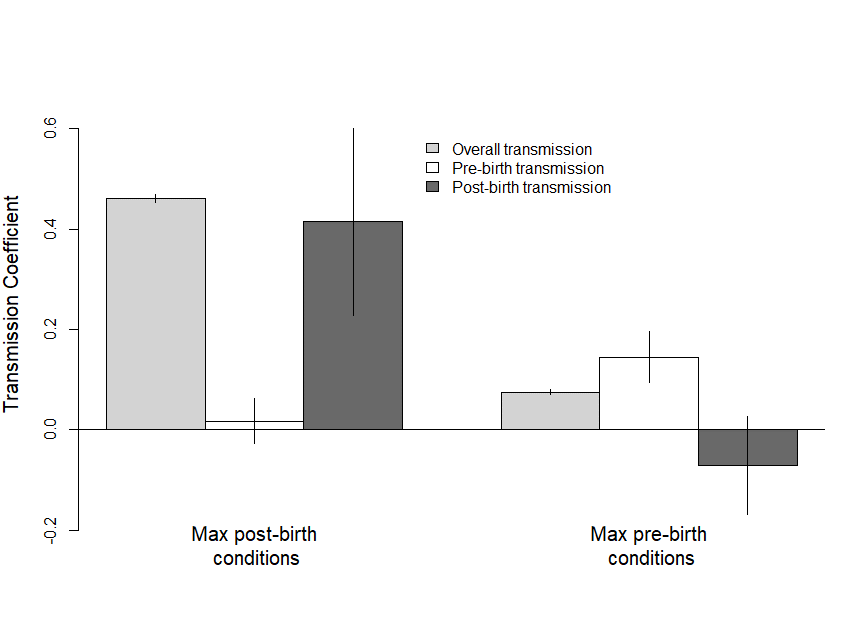

In the final step of the analysis, we show that the relative importance of the biological and social transmission pathways differs quite dramatically depending on the individuals’ age, living conditions, and consistency of the parental cues they receive. In essence, the social and biological pathways behave like communicating vessels such that the conditions that amplify the social transmission at the same time inhibit the biological mechanisms, and vice versa. Thus, in certain situations, the parent-child similarity in voter turnout is almost fully accounted for by social factors, whereas under other circumstances, genetic and biological factors are more decisive for the transmission of political inequality across generations.

We summarize these findings in Figure 1. The height of the bars in Figure 1 corresponds to the magnitude of the transmission coefficients under conditions that we expect to be maximally conducive to amplified post-birth effects (leftmost triplet) and pre-birth effects (rightmost triplet). When evaluating the strength of the parent-child correlations at these extreme points a clear pattern emerges. For young individuals (aged 18) living with parents who are consistent voters or abstainers, the overall transmission of turnout propensities is fully accounted for by social or post-birth factors. At the other end of the spectrum, we can see that for older (aged 50) individuals who have left their parents’ home and whose parents are inconsistent in their turnout behavior, the overall transmission is, instead, fully accounted for by genetic and biological pre-birth factors.

Intergenerational transmission in turnout behavior under maximum and minimum conditions

These findings are important for several reasons. Above all, we believe that our study constitutes an important and fruitful step towards integrating the traditional political socialization and the more recent behavior genetics approaches to understanding parent-child similarities in political traits.

Moreover, a better understanding of the causes of intergenerational associations in voter turnout provides us with important clues as to how persistent political inequalities may be most effectively counteracted. For instance, if the parent-child similarity in turnout behavior is mainly the result of parental socialization, this implies that policies reducing the differences in political commitment and activity in one generation will automatically reduce political inequality in subsequent generations. Alternatively, if parent-child concordance is primarily channeled through genetic pathways, it suggests that the battle against political inequality must be waged anew each generation.

This blog piece is based on the article “Persistent Inequalities: The Origins of Intergenerational Associations in Voter Turnout” by Sven Oskarsson, Rafael Ahlskog, Christopher T Dawes, and Karl-Oskar Lindgren, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, July 2022.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the Journal of Politics and replication materials are available at The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the authors

Sven Oskarsson- Uppsala University

Sven Oskarsson is a Professor in the Department of Government at Uppsala University. His research interests include political representation and participation and social science genomics. You can find further information regarding his research here.

Rafael Ahlskog- Uppsala University

Rafael Ahlskog is an assistant professor in political science at the Department of Government at Uppsala University. His research interests are in political behavior, social genomics, and health policy. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @RAhlskog

Karl-Oskar Lindgren- Uppsala University

Karl-Oskar Lindgren is an Associate Professor in the Department of Government at Uppsala University. His research interests include political representation and participation and labor market politics. You can find further information regarding his research here.

Christopher T. Dawes- New York University

Christopher T. Dawes is an Associate Professor in the Wilf Family Department of Politics at New York University. His research interests include political behavior and sociogenomics.