The Black Lives Matter Movement is officially more than a decade old. In its longevity, it has proven itself an enduring force in American politics. It has certainly been an enduring force in the research trajectory that has led to our new Journal of Politics piece: “Contact and Context: How Municipal Traffic Stops Shape Citizen Character.”

The three of us—Allison Anoll, Derek Epp, and Mackenzie Israel-Trummel—were in graduate school when the movement coalesced. Following the not-guilty verdict of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin, protests erupted across America, and have reemerged multiple times in the wake of policing violence, including the widespread 2020 protests. As we write this post in fact, BLM activists are mobilizing the city of Grand Rapids following the death of Patrick Lyoya at the hands of a police officer.

BLM protesters have repeatedly emphasized a key point: contact with punitive institutions in the U.S. is racially unequal. And when carceral contact occurs, the state teaches people about their place in society. Discriminatory and invasive contact with the state can depress political engagement, demobilize citizens, and in the long run, undermine trust and legitimacy in governance. Further, direct contact can spiral outward, shaping the attitudes and participatory practices of those who observe their loved ones’ experiences with the criminal justice system.

Those laboring to spread these ideas both in America’s streets and universities have shaped each of our research trajectories, guiding our interests in political participation, race, and government policy toward the American carceral state. In this paper, we build on all these ideas to ask: are Americans who do not experience direct or proximal contact with the state—and yet still live in places where they can observe discriminatory practices on the part of the police—shaped by the state’s behavior too?

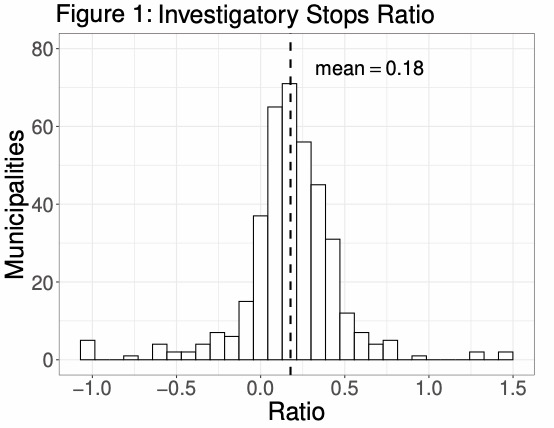

Combining bureaucratic data on traffic stops with survey data from Black and White respondents, we examine how racial disparities in local policing practices shape the attitudes and participatory choices of people living in these contexts, regardless of whether they have directly experienced the criminal justice system in recent years.

We combine this traffic stop data with survey data of Black and White respondents in these two states. We match respondents to their municipality, which gives us information about the attitudes and participatory behaviors of people in each of these contexts and their histories of personal and proximal contact. Using this individual-level data, we can determine how municipal context relates to attitudes towards the police and self-reported political participation after controlling for a wide range of covariates and personal and proximal contact.

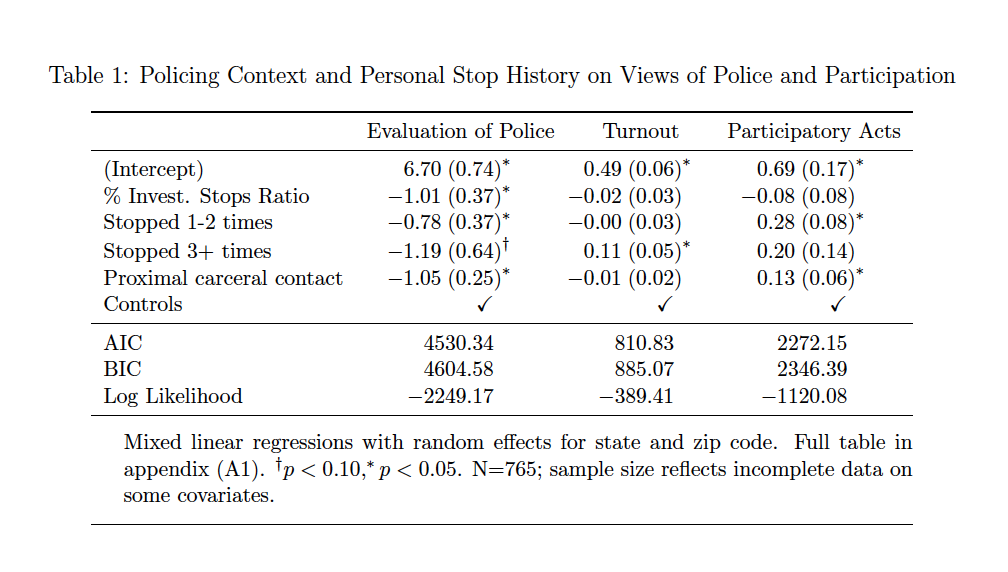

Table 1 shows our results. We find that personal and proximal contact degrade evaluations of the police, in line with previous work—but so too do disparities in municipal-level policing practices. In fact, people who live in the most anti-Black policing contexts compared to racially equal ones are expected to negatively evaluate the police to a larger degree than those personally stopped one or two times in the preceding five years. Context matters for how Americans evaluate the character and quality of their state.

But our findings also show this relationship is limited to evaluations of the police. Municipal disparities do not relate to political participation, either for turnout or other forms of engagement such as protest. Instead, those who are stopped most frequently are more likely to vote, and—as shown in studies that came before us—proximal carceral contact mobilizes non-voting political participation.

What does this mean for the broader movement to reform policing? One solution is clear: policymakers and police departments should work to reduce racial differences in policing. The consequences of these disparities appear to ripple far beyond the communities subjected to them and others have shown that declines in trust like those we document can have negative externalities for municipal governance including crime reporting and violence levels. Still, our findings suggest that the Americans most likely doing the hard work of mobilization and policy engagement as through the BLM movement are not those who observe disparities from afar, but those with direct or proximal experiences.

This blog piece is based on the article “Contact and Context: How Municipal Traffic Stops Shape Citizen Character” by Allison P. Anoll, Derek A. Epp and Mackenzie Israel-Trummel, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 3.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Allison Anoll is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University, where she studies how social norms and social context affect political participation and attitudes. More information about her research, including her recent book, The Obligation Mosaic: Race and Social Norms in US Political Participation, is available here on her website.

Allison Anoll is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University, where she studies how social norms and social context affect political participation and attitudes. More information about her research, including her recent book, The Obligation Mosaic: Race and Social Norms in US Political Participation, is available here on her website.

Derek Epp is an Assistant Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies policing and the policymaking process. More information about his research is available here on his website.

Derek Epp is an Assistant Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies policing and the policymaking process. More information about his research is available here on his website.

Mackenzie Israel-Trummel is an Assistant Professor of Government at William & Mary. She studies American political behavior, and her interests include the politics of identity and the carceral state. More information about her work is available here on her website and follow her on Twitter: @DrMackIT