The three reform acts in the UK (in 1832, 1867, and 1884) are among the most consequential events in 19th century British politics: they expanded the franchise and reformed the electoral system – essential steps for the UK’s trajectory towards modern-day politics as we know it. Thanks to the Eggers-Spirling database of British Political Development, political scientists have been able to study exactly how political behaviour and institutions changed over the course of these reforms. For example, existing work documents the beginning of voters voting along party lines (and an associated decrease in split ticket voting); the emergence of disciplined parties whose MPs all vote the same way; and the crystallisation of legislative conflict between the government and the opposition.

One aspect that has not been extensively studied yet concerns the genesis of modern-day political careers, and the power of political parties in shaping them. At the beginning of the 19th century, politicians obtained a seat in Parliament by means of patronage and personal connections – especially in so-called rotten boroughs. First-time candidates would routinely win entry into the House of Commons this way, and party elites had little say over who would be nominated and elected. By the end of the century, however, the picture had changed completely: political parties now had a tight grip on nomination control in constituencies throughout the UK; prospective politicians proved their worth in ‘hopeless’ constituencies before running and winning in a party’s safe seat, and continued climbing an increasingly steep seniority ladder by rising through the ranks of stepping-stone offices on their way towards Cabinet positions.

In our paper we document how, gradually and after each reform act, parties increased their control over the nomination process as increasingly safe Liberal or Conservative seats emerged. We combine the Eggers-Spirling data with additional sources from before the first reform act to trace these developments throughout the 19th century in British politics.

Nominations became more valuable as constituencies became more reliably Conservative or Liberal

First, we show that, as voters became more reliably partisan, so did constituencies. We calculate a “seat safety index” and demonstrate that, after every reform act, the number of safe Conservative and Liberal seats increased, while the number of genuinely competitive seats (barring landslide victories) that would regularly switch hands decreased. This development placed more power in parties’ hands: as voters increasingly oriented their ballots around partisan labels, the “value” of securing a Liberal or Conservative nomination increased. Put differently, in an era where politicians won votes based on personal connections, they could win without a partisan label; but when voters determined their ballot based on the party label, securing that party’s nomination became essential.

Once Nominated, Career Safety Increased

Next, we document that nominations also became more valuable because a growing incumbency advantage meant safe re-election. Election losers were always less likely to contest future elections, but we show that, conditional on running again, their probability of winning decreased throughout the century, while election winners would be safely re-elected. We also show evidence for this growing incumbency advantage using both descriptive statistics as well as regression discontinuity designs.

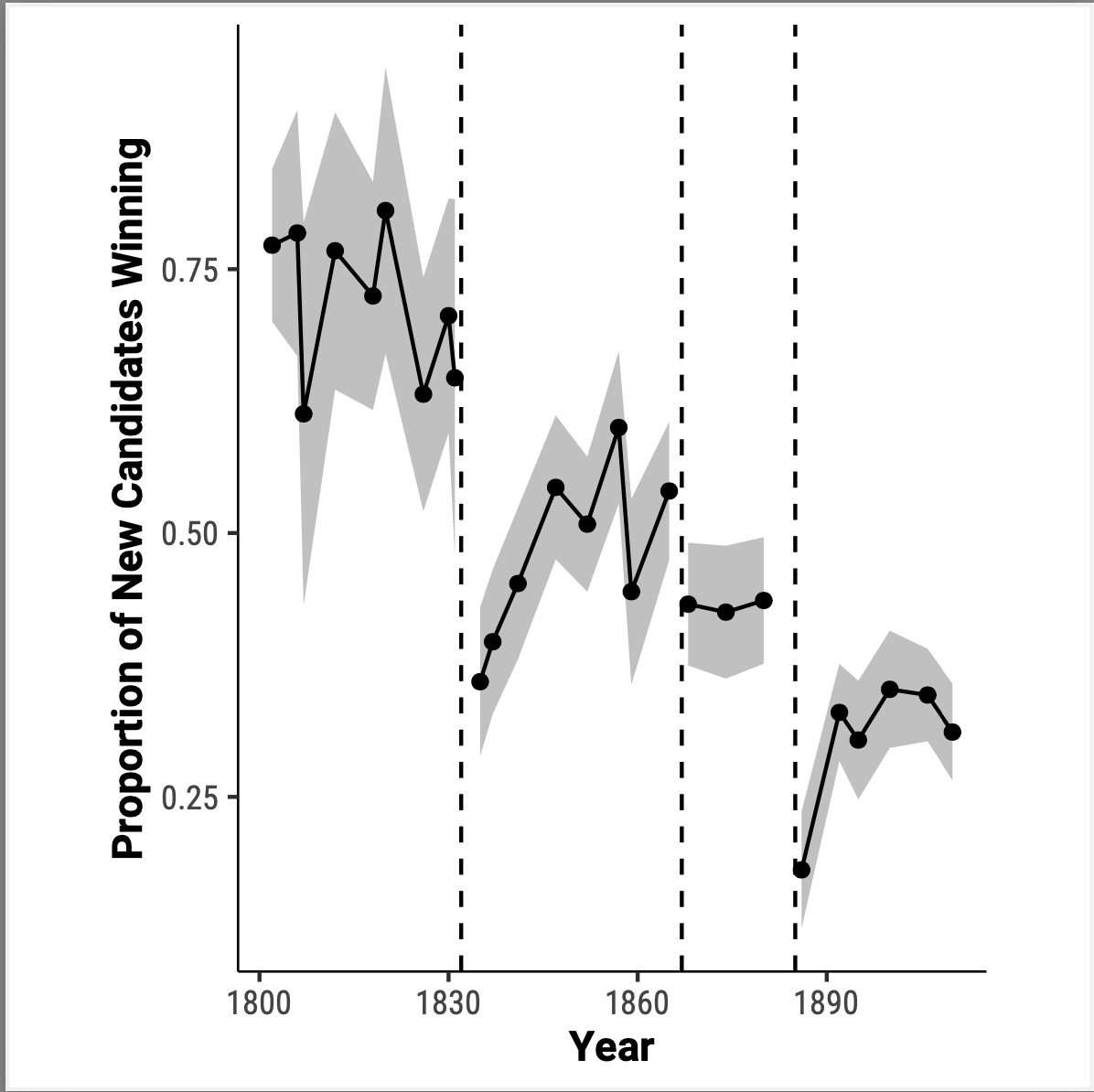

Increased Competition Means First-Time Candidates Started Worse Off

If nominations in safe seats became increasingly valuable, and reserved for incumbents, where does this leave new, prospective politicians? We show that, over time, the proportion of new candidates (who have never run before) who win outright election drops dramatically. Over the course of the 19th century, the average first-time candidate has to cut their teeth in increasingly difficult-to-win seats. As the accompanying figure shows, before the first reform act, up to three quarters of first-time candidates would win a seat; this proportion dropped to as little as one quarter after the third reform act.

We also present additional evidence that candidates’ path towards becoming an MP became gradually harder: after each reform act, candidates started off in more hopeless seats and had to improve their chances bit by by with every election attempt; they also increasingly had to switch constituencies – a growing proportion were first elected only after they contested a second constituency, and increasingly, such switches were towards safer / more winnable seats.

Career Paths Became More Gradual Within Parliament

It’s not just nominations and first successful elections that became more difficult and protracted. We document how, throughout the 19th century, a norm for an office hierarchy developed and junior MPs had to work through a growing sequence of stepping-stone offices before entering Cabinet. We identify key stepping stone offices and show that, over time, these offices became more predictive of MPs’ ascent to Cabinet.

Conclusion

All of these changes contributed to a strong norm of party control over nominations, and came to shape political careers in Westminster systems: newcomers were increasingly forced to accept unwinnable assignments and run in hopeless campaigns before switching into more promising seats that may have been vacated by previous incumbents. This development of a seniority norm also continued once in Parliament: specific stepping-stone offices became necessary before entering Cabinet, and those in the highest rungs of the party were also rewarded with the safest seats.

While we cannot pinpoint a specific event or one of the three reform acts as the most important one, we document that by the time the third reform act came into full effect, the transformation of party careers into their modern-day version was complete. Our paper thus shines a light on an important dimension of political development in Westminster systems, and opens an avenue for future research – for example, how the pipelines we document changed in postwar Britain, or whether and how similar developments took place in other polities (e.g., Scandinavia or the US).

This blog piece is based on the article “The Emergence of Party-Based Political Careers in the UK, 1801-1918” by Gary W. Cox and Tobias Nowacki, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 4.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Gary W. Cox is the William Bennett Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University. In addition to numerous articles in the areas of legislative and electoral politics, he is the author of The Efficient Secret, Making Votes Count and Marketing Sovereign Promises, co-author of Legislative Leviathan and Setting the Agenda. A former Guggenheim Fellow, Cox was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1996 and the National Academy of Sciences in 2005.

Tobias Nowacki is a Ph.D. Candidate in political science at Stanford University, specialising in the political economy of elections and applied methodology. His research focuses on how electoral rules and institutions shape political careers, representation and policy outcomes, using administrative and election data in the US and Europe. You can find more information on his research here and follow him on Twitter: @TobiasNowacki